The dangerous breakdown of the rule of law

People are being arrested and convicted for crimes that do not exist.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Marie Dinou is reportedly one of the first people to have been convicted under the Coronavirus Act 2020.

Dinou was approached by police officers at Newcastle Central railway station. Officers claimed she was ‘loitering between platforms’. They asked her why her travel was ‘essential’, but she refused to explain and was arrested. Dinou was eventually convicted of ‘failing to provide identity or reasons for travel to police, and failing to comply with requirements under the Coronavirus Act’. She was fined £660 for breaching the Act, £85 for ticket fraud – she had apparently attempted to travel without a ticket – and was also ordered to pay £80 in costs.

The case has provoked a justified backlash. Dinou has been prosecuted for refusing to disclose private information to the police. In a free country, no one should ever be criminalised for refusing to speak to the police. Even on its own terms, this prosecution is outrageous.

Yet the case also raised other issues. It soon transpired that the conviction was completely wrong in law, too. The Times reports that Dinou had been prosecuted under Schedule 21 of the Coronavirus Act, which was brought in to compel people to self-isolate or be screened if they are suspected of having the virus. But there was no suspicion that Dinou was infected. And there is no power under the Act which allows the police to stop someone and demand he or she provides them with information. The police have now conceded that Dinou should not have been prosecuted and that her conviction ought to be quashed on appeal. This is after she spent 48 hours in police custody prior to her court appearance.

The Dinou case raises serious questions about the rule of law during a pandemic. Dinou was arrested, charged and then prosecuted in a court of law for an offence that does not exist. The case was heard in court by a district judge rather than a bench of magistrates. It was reported that the judge convicted Dinou in a single hearing, even though she reportedly refused to leave her cell throughout the proceedings.

This wrongful conviction is not simply the result of negligence. It shows the real risk of the rule of law being undermined in an emergency. This is not to say that anyone involved in prosecuting Dinou knew that they were acting unlawfully. But it does suggest that the authorities are becoming far more relaxed about keeping their own power within the limits of the law than they should be.

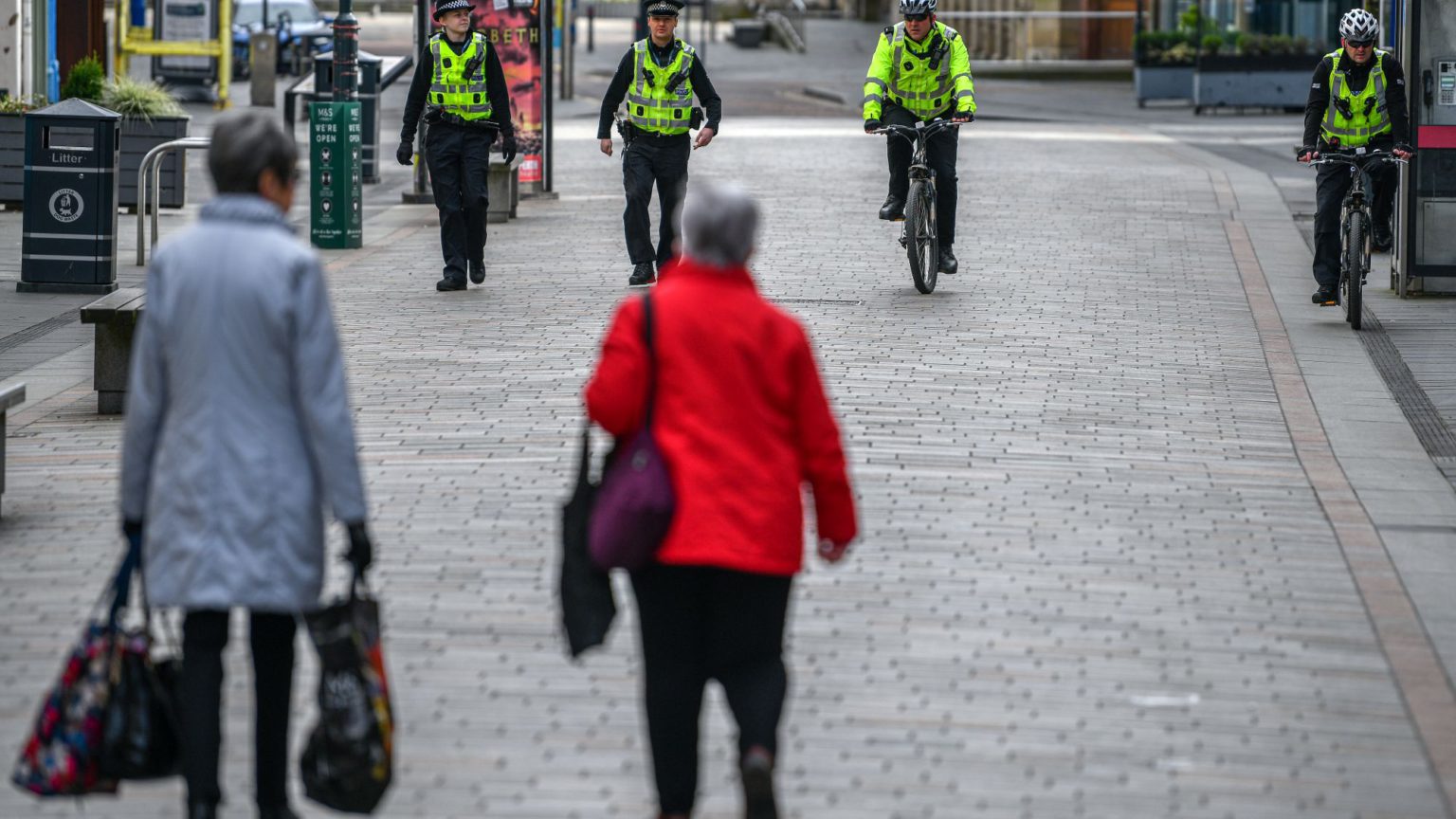

Dinou’s prosecution follows other stories of police overreach since the UK entered lockdown – from police officers using drone footage to shame people walking in large open spaces to officers telling shops that they are forbidden from selling items deemed ‘non-essential’. None of these assertions of power is backed up by law. New guidance has since been issued by the College of Policing, which instructs officers to refrain from enforcing the law too heavy-handedly. But the broader legal issues which have arisen from the state’s response to the pandemic cannot be solved by flimsy and toothless guidance alone.

After all, the enforcement of the lockdown is not the only area in which the rule of law is in retreat. The courts system is rapidly adapting to the pandemic and traditional protections for defendants are going by the wayside. Defendants who might ordinarily be considered for bail are struggling to have their cases heard because the courts are closed to all except the most urgent cases. The Scottish government had even proposed ending trial by jury to allow for trials to proceed, though this proposal was thankfully dropped.

This pandemic will set precedents which could shape our thinking about freedom for decades to come. Will we see a public-health exemption built into the law to allow for the suspension of juries if it risks the health of the nation? If prisoners can be effectively locked down during a pandemic, then in what other circumstances can their rights be suspended? We are creating an environment in which our long-held Common Law principles of fair treatment, restrained power and the right to be judged by our peers could be sacrificed in the name of public safety.

The pandemic has made it abundantly clear that the law is a very weak protector of our freedoms. But it has also shown the importance of the rule of law to a functioning democracy. Of course, the rule of law is not absolute. There are times when it is morally right for individuals to disobey the law. What matters is that the power of the authorities over the people is properly restrained. This is why we must defend the authority of our laws, even in times of significant crisis.

Luke Gittos is a spiked columnist and author. His latest book Human Rights – Illusory Freedom: Why We Should Repeal the Human Rights Act, is published by Zero Books. Order it here.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.