Literature for the lockdown

Andrew Doyle on the books we should all read to make the most of self-isolation.

In his 1891 essay, The Soul of Man Under Socialism, Oscar Wilde makes the case for the cultivation of the individual through those periods of leisure that he believes will emerge after the abolition of private property, the rejection of materialism and the creation of mechanical slaves. And although the lockdown brought about by the coronavirus pandemic was hardly what Wilde had in mind, it has at least afforded many of us more leisure time to read those lengthy tomes that have been languishing on our book shelves and taunting us for years.

Let’s start with George Orwell, who wrote a favourable reappraisal of Wilde’s essay in 1948. Many of us will already be familiar with his major novels, Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), and his better known non-fiction works, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) and The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), but his essays are more often quoted than read in their entirety. John Carey’s edition of Orwell’s essays for the Everyman’s Library runs in excess of 1,350 pages, which will occupy at least a fortnight if read with care.

The scope is immense, ranging from Orwell’s reflections on his experiences fighting against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War to the most efficient method of making a decent cup of tea. The essays span the last two decades of his life, and reveal as much about himself as the subjects he chooses to dissect. He is consistently insightful, occasionally mean-spirited, and more often right than wrong. His honesty can be disarming, such as when he fantasises about driving ‘a bayonet into a Buddhist priest’s guts’ in ‘Shooting an Elephant’, or his general squeamishness about homosexuality (he dismisses WH Auden and Stephen Spender as ‘fashionable pansies’).

Orwell has his recurring bugbears: the imperialistic middle-class ‘Blimps’ and the anti-patriotic left-wing intelligentsia, writers who indulge in cliché and ‘the endless use of ready-made metaphors’, and anyone who adheres slavishly to any given political ideology. His writing on literature is particularly enjoyable, even when his political worldview gets the better of his artistic judgements. Another idea which seems to preoccupy him, most frequently in his later years, is the conviction that humanity is ill-equipped to cope with its loss of faith in personal immortality, which he considers to be ‘the major problem of our time’.

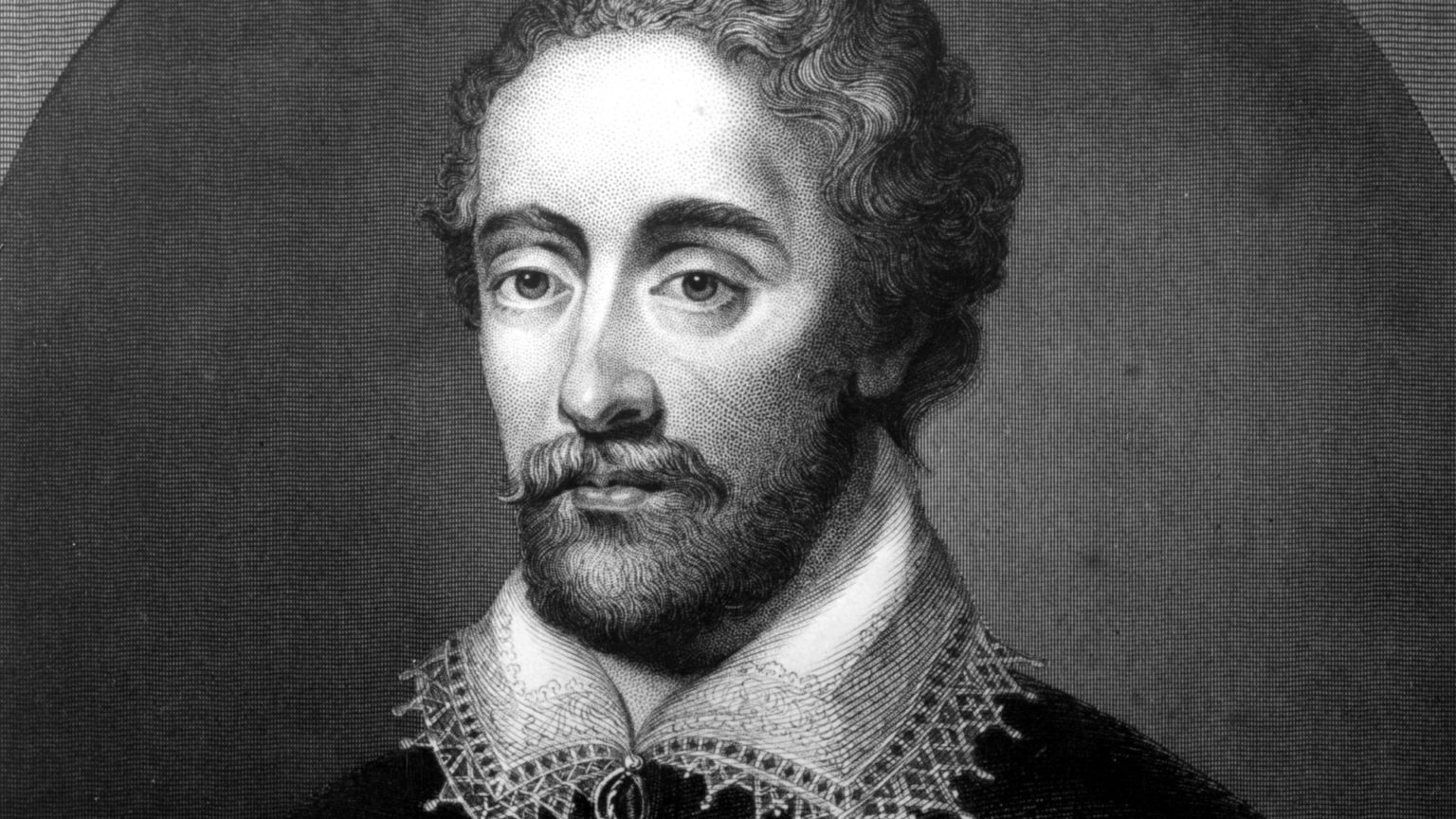

I’m not so sure that a general decline in religion need deprive us of a sense of the numinous, but for those who are interested in themes of despair and redemption, one could do a lot worse than delve into the great epic poems of our language. The tendency to convince ourselves that they are not worth reading makes sense, especially when modern editions of Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590) or John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) are invariably engorged with endless footnotes and appendices. There’s a copy of Spenser’s magnum opus in the library at St John’s College, Oxford, containing a handwritten note allegedly written by the poet Philip Larkin during his studies: ‘First I thought Troilus and Criseyde was the most boring poem in English. Then I thought Beowulf was. Then I thought Paradise Lost was. Now I know The Faerie Queene is the dullest thing out. Blast it.’

We can forgive the curmudgeonly undergraduate his frustration, but we shouldn’t take his criticism too seriously. If I were to recommend just one of the great English epic poems it would be The Faerie Queene. Each of the six completed ‘books’ has its own protagonist, a knight who undertakes a quest relating to the virtue that he or she embodies. For a self-conscious effort at creating the foundation for a new national literature, there are all the expected witches, dragons and monsters of bygone medieval folklore, but with a political focus very much of its time. Spenser’s allegories are often explicit but occasionally abstruse; such ambiguities make it impossible for the reader to remain passive. Given the current climate, the Redcrosse Knight’s sojourn in the Cave of Despair feels particularly germane.

Some will be put off by Spenser’s neologisms and pseudo-archaic turn of phrase, but with persistence one attunes to the style. There’s something very satisfying about this kind of immersion in an unfamiliar register. One finds it in the narrative voices of Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy (1992), the two competing accounts of the kidnapper and the kidnapped in John Fowles’ The Collector (1963), and, most strikingly, the concocted patois known as ‘Nadsat’ in Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (1962). I am reliably informed that many readers of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) experience a similar process of acclimatisation, although the last chapter of Ulysses (1922) – 22,000 words without punctuation – was enough to put me off seeking out another one of his books for the foreseeable future. If that makes me a philistine, then so be it.

As far as novels go, this would be an ideal time to explore the lesser read works by canonical authors. Salman Rushdie is probably my favourite living novelist, and although Midnight’s Children (1981) and The Satanic Verses (1988) are undeniably brilliant, I am more inclined to recommend Shalimar the Clown (2005) to those unacquainted with his work. The story crosses time, cultures and continents, and yet it is, at heart, motored simply by revenge. Rushdie’s depiction of Kashmir’s degeneration from an ecumenical paradise to a sectarian warzone is heart-breaking. No doubt partly inspired by the fatwa against its author, Shalimar the Clown is a cautionary tale about the evils of fundamentalism – as relevant now as it ever was.

Then there are those novelists who have been unjustly consigned to oblivion, thanks to the capricious nature of literary trends. Into this category I would place Stella Benson, the novelist, poet, feminist and travel writer whose neglect is wholly undeserved. Her first novel I Pose (1915) was widely acclaimed, but it was far too eccentric to enjoy commercial success. Everything about the piece is off-kilter, from the characterisations and dialogue to the structure itself (there are only two chapters; the first runs for 356 pages and the second for 10). Neither of the two leading characters are named. They are known only as ‘the gardener’ and ‘the suffragette’. They meet by chance on a country road while the latter is on her way to burn down a house as a protest against female disenfranchisement, and eventually travel together to the West Indies.

Benson’s narrative voice is obsessed with the performativity of human emotion, and draws attention to its own inauthenticity. Of the suffragette, Benson notes that ‘her eyes made no attempt to redeem her plainness, which is the only point of having eyes in fiction’. Later, she tells us that ‘the gardener had a morbid craving for unpopularity, it was part of the unique pose. Unpopularity is an excellent salve to the conscience, it is delicious to be misunderstood.’ When the question of votes for women is raised, the narrator reassures us: ‘You need not be afraid. There is not going to be so very much about the cause in this book.’

If these metafictional gestures are audacious, the lurches in tone from comedy to tragedy are even more so. For instance, just as we become accustomed to the archness of her satire, Benson plunges us into the all-too-real aftermath of an earthquake.

‘Distracted men and women panted and moaned and tore at the wreckage with bleeding hands. A little crying crowd was collected round a woman who lay nailed to the ground by a mountain of bricks, with her face fixed in a glare of terrible surprise. By the cathedral steps the dead lay in a row, shoulder to shoulder, with the horrid uniformity of sprats upon a plate.’

The image is completed by the addition of a ‘little dog, which ran around looking for its past in the extraordinary mazes of the present.’

I Pose is not Benson’s best book, but there is something to be said for reading a novelist’s work in chronological order. For those who prefer to experience Benson at the height of her powers, it would be better to start with The Poor Man (1922), Pipers and a Dancer (1924) or Goodbye Stranger (1926). Her last completed work, Tobit Transplanted (1930), is near perfect, although I can see no reason why she felt the need to include the source material (the Book of Tobit from the Old Testament) as a postscript. The story would be more effective without the explicit association, which is also why I prefer the novel’s original title The Far-Away Bride.

At the risk of further self-indulgence, I’ll leave you with one more recommendation for this period of national quarantine. In Orwell’s essays he repeatedly borrows GK Chesterton’s concept of the ‘good bad book’. In addition, he identifies a category of ‘perverse and morbid books’ that create a world of their own, into which he deposits Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë and The House with the Green Shutters (1901) by George Douglas Brown. To this I would add Sabine Baring-Gould’s Mehalah: A Story of the Salt Marshes (1880). Comparisons with Wuthering Heights are inevitable and, in the shadow of Brontë’s masterpiece, Mehalah was always likely to be plunged into obscurity. It’s curious to think that the Anglican priest who wrote the famous hymn ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ should have also penned this crazed account of intense sexual obsession.

The lawless marshlands of East Mersea in Essex form a backdrop to the bleak and bizarre story of Elijah Rebow, the sadistic landowner whose desire for Mehalah leads him to commit increasingly psychotic acts. Mehalah herself is no damsel in distress; she can fight as well as any man, having lived an amphibian existence amid the smugglers and pirates that occupied Mersea Island in the 19th century. In one of the local churches hangs a display of the Ten Commandments with all the ‘nots’ erased. ‘It cannot be denied’, writes Baring-Gould, ‘that the parishioners conscientiously did their utmost to fulfil the letter of the law thus altered’.

The melodrama might be too much for some – that Elijah keeps a mad brother chained up in his basement is the least of the novel’s excesses – but this endlessly surprising work deserves to be better known. In this time of great uncertainty, Baring-Gould’s strange and godless story finds an unexpected resonance.

Andrew Doyle is a stand-up comedian and spiked columnist. He is doing a live tour with Douglas Murray in the spring, called ‘Resisting Wokeness’. Get tickets here.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.