Against eugenics

From yesteryear’s eugenicists to today’s expert class – the elite thinks it is superior to ‘the mob’.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

A big row has erupted over eugenics. Dominic Cummings, the key adviser to the prime minister Boris Johnson, as part of his drive to recruit ‘misfits and weirdos’, has hired Andrew Sabisky as a Downing Street aide. In the past, Sabisky has argued that there are significant genetic differences between races, which has provoked an understandable backlash. He has now resigned.

The science writer Richard Dawkins stirred the pot some more when he seemed to suggest that ‘eugenics’ – the science of ‘good breeding’ – could be applied to the human species. Dawkins said he deplored eugenics on ‘ideological, political, moral grounds’, but that did not mean it would not work in practice, as it does on ‘cows, horses, pigs, dogs and roses’. ‘Just as we breed cows to yield more milk, we could breed humans to run faster or jump higher’, he said in a follow-up tweet. Spectator editor Fraser Nelson tweeted that he had written an article about the supposed ‘return of eugenics’ in 2016.

To many, Sabisky’s appointment was a sign that the government is nursing a secret Social Darwinist agenda. Dawkins was roundly pilloried as a new Hitler for arguing for the viability of a eugenics programme. Guardian journalist Owen Jones turned on Nelson to accuse him and his magazine of fomenting a full-on racist campaign. Jones even demanded a cordon sanitaire around the Spectator, the country’s oldest and most successful political weekly.

It was the critic Sydney Smith who said, ‘I never read a book before reviewing it; it prejudices a man so’. More than a century later, Smith has a willing student in Jones, who reluctantly conceded that the Fraser Nelson piece he had denounced for promoting eugenics was no such thing. On the contrary, it was a sustained argument against eugenics. Truth is only a secondary matter, it seems, when there is the Greater Truth that all conservatives are really Nazis.

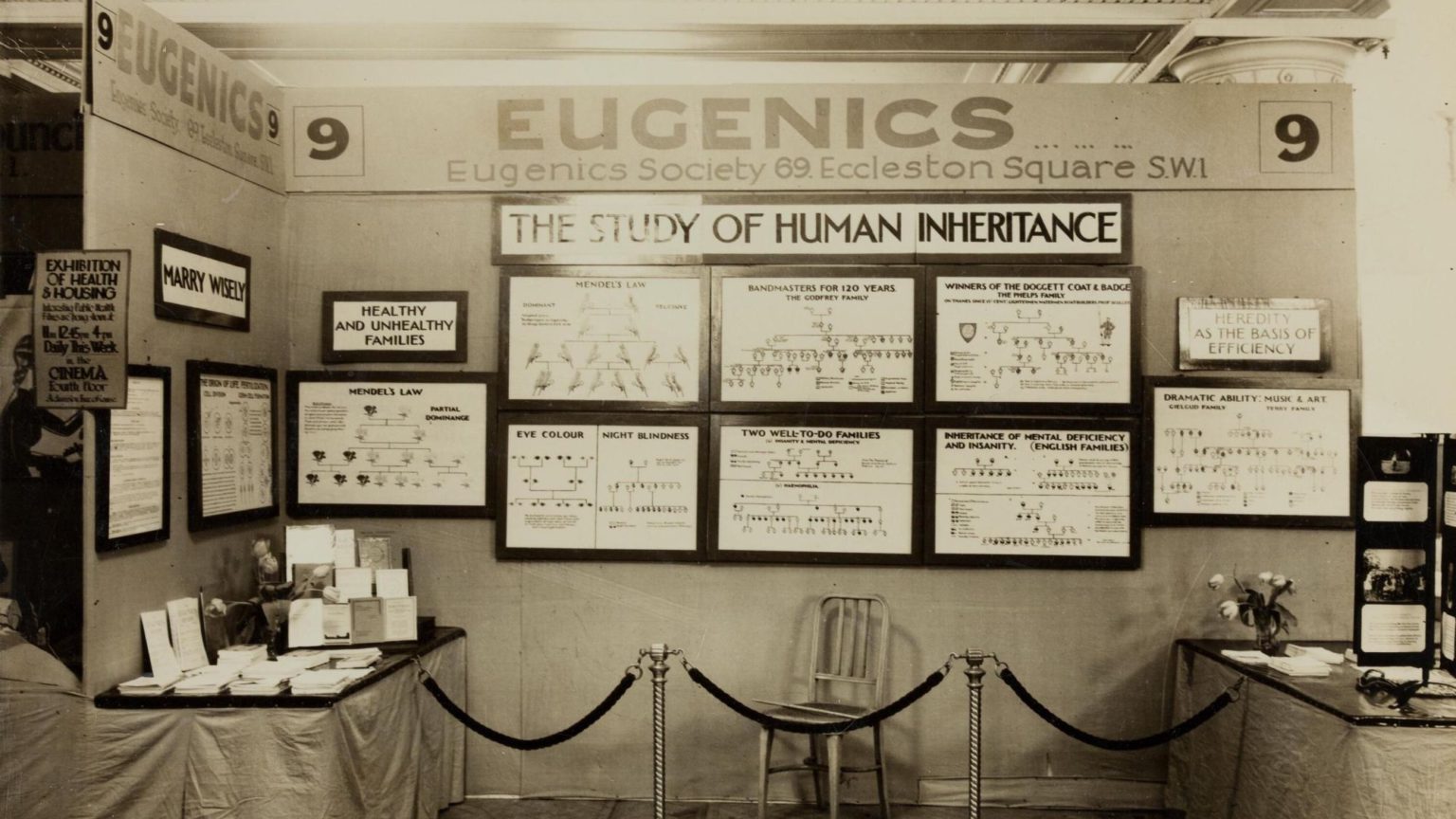

But when eugenics was a serious movement, it was not some underground philosophy advocated by the ‘alt right’. Eugenics was a movement created by mainstream scientists and advocated by mostly liberals and progressives. The initial opposition to eugenics came mostly from conservatives – reactionaries, even – who, for Christian reasons, were upset by the idea of meddling with God’s will.

The precursor to ‘eugenics’ was the philosophy that overbreeding creates famine, as argued by the cleric Thomas Malthus in his Essay on the Principle of Population. It was this Malthusian overbreeding argument that the chief government adviser Nassau William Senior drew on when he argued hard against famine relief in Ireland, with terrible consequences.

(It was of course not ‘God’s will’ at all that the Irish should starve, but the will of their mostly English landlords, who despaired of the low rents they gave up, and leapt on the chance to pack them off to America or to leave them to die in ditches.)

Charles Darwin’s elucidation of the law of evolution in 1859 upset many traditionalists, and it is, to this day, the accepted understanding of heritability and mutation in the origins of species (reinforced by Watson, Crick and Franklin’s identification of the ‘DNA’ molecule that is the carrier of genetic inheritance).

In the late 19th and early 20th century there was a vogue for ‘rational’ social administration led by New Liberal reformers like Sydney and Beatrice Webb, Joseph Chamberlain, Charles Booth and William Beveridge, drawing on earlier reform activists like Herbert Spencer (who coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’) and Henry Mayhew. These reformers and social scientists were ably assisted by natural scientists, the most important of whom was Francis Galton.

Galton, a cousin of Darwin’s, was a keen science populariser. He was a leading light in the British Society for the Advancement of Science, the Royal Geographical Society, the Royal Society, and many others. For all his many accomplishments in statistics and cartography, Galton dedicated much of his energy to the promotion of the science to which he gave the name ‘eugenics’ (from the Greek eugenes, meaning ‘well-born’).

Galton used his official positions to spread the idea that the human species was differentiated according to its mental, moral and physical capacities, which were innate, inherited characteristics. Tragically, Galton’s idea gained a great deal of traction with those of his peers who thought that they could apply scientific reasoning to government.

As well as conservatives, leading socialists and liberals embraced the new science. Eugenicist thinking helped to explain away the failure of democratic societies to raise their citizens all up together. Poverty could be framed as a problem of human biology rather than of class divisions.

Eugenics also held up the (illusory) prospect that social problems could be overcome by sterilising ‘idiots’. Birth-control campaigner Marie Stopes argued for the reduction of the ‘hordes of defectives’ through contraception. ‘The time is surely coming’, argued the socialist academic Harold Laski, ‘when society will look upon the production of a weakling as a crime against itself’.

Economist John Maynard Keynes and prime minister Neville Chamberlain were members of the Eugenic Society, which still exists today under the name of the Galton Institute. London County Council put out posters outlining how many ‘defectives’ were born each year, to account for the pressure on social services. A Parliamentary report of 1934 recommended voluntary sterilisation for the ‘unfit’.

In the colonies, where white minorities ruled over large non-white populations, the appeal of the racial science was even greater. Colonial administrators readily adopted the self-serving view that the European races were destined to rule. At its worst, this application of racial science to colonial administration led to Lord Lindemann’s advice to Churchill (advice he gleefully reworded as ‘they breed like rabbits’) against providing any relief for the Bengal Famine of 1943.

After Nazi Germany’s death camps were opened at the end of the Second World War, there was widespread revulsion at the application of science to human breeding, as it became clear where it could end up. ‘Is it really true that a “scientist” is any likelier than other people to approach non-scientific problems in an objective way?’, asked George Orwell: ‘There is not much reason for thinking so. The German scientific community, as a whole, made no resistance to Hitler.’

The taboo against eugenics is a good one. The Christians are right about man being unique compared to animals and plants. Nevertheless, the willingness of some to project support for a eugenic programme on to those they disagree with is alarming. It is a pseudo-intellectual version of ‘every who disagrees with me is Hitler’.

One depressing similarity between the era of eugenics and today is the underlying hostility to democracy that pervades much of the intelligentsia. It seems that you do not need a Nazi certificate of good Aryan stock to be of higher worth. For many today, just a degree makes you a superior person to your less-lettered neighbour.

When Brexit-backing minister Michael Gove had the temerity to suggest that experts do not get everything right, he, and everyone who was not a PhD, was pilloried by the intelligentsia as ‘unqualified’ to make decisions on such matters of state so grave as whether we should be in the European Union. Experts today say we cannot even be trusted with intimate and private decisions as to whether we should eat sweets or smoke. Then as now, even without ‘scientific’ backing, elites in Britain believe they are well-bred and the lower orders are degenerate.

But one lesson of history is that experts often do get things badly wrong. Eugenics is a prime example. Government advisers like Francis Galton, Frederick Lindemann and Nassau Senior had pseudo-scientific backing for their deadly policies of weeding out the unfit and starving the ‘overbred’.

There are scientists today who want to investigate the question of IQ, heritable intelligence and more. They are supported by some right-wing gadflies who enjoy the ‘disruptive’ potential of resurrecting IQ science to ‘own the libs’. One suspects Andrew Sabisky to have been acting in this vein, and that Dominic Cummings most likely knew his past comments would provoke a backlash.

The scientists who are looking for intelligence or character in DNA are most likely on a fool’s errand. In particular, the attempt to make the prejudice-based racial categories of the 19th century map on to genetics is based on a grievous misunderstanding. In reality, skin colour is totally useless as a marker of biological differences.

Richard Dawkins is at least right about one thing: if science did discover a genetic basis to differences in intellectual ability, social class or even race, that in itself would not be a reason for abandoning the moral argument for equality or human agency. No line of scientific inquiry should be foreclosed ahead of its investigation. But by the same token, society ought always to have the final say about social policy, whatever the experts say.

James Heartfield is co-author of The Blood Stained Poppy, published by Zero Books. Order a copy here.

Picture by: Wellcome Collection, published under a creative commons licence.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.