‘Class can predict how you’ll live, but not how you’ll vote’

James Tilley on the decline of class voting and the exclusion of the working class.

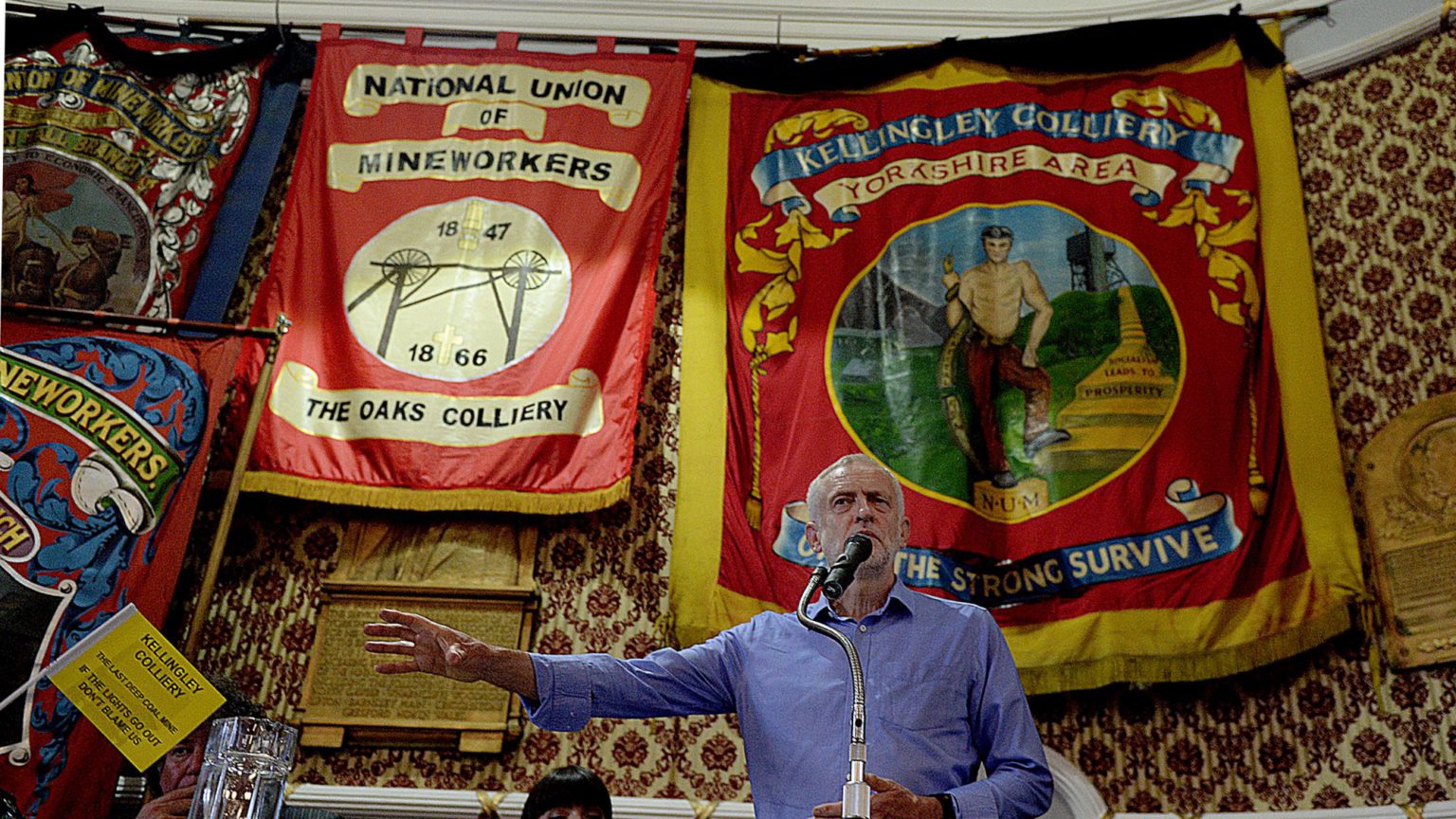

At the last General Election, seats which were once considered to be Labour’s traditional heartlands flipped to Boris Johnson’s Conservatives. Post-election polling by YouGov found 48 per cent of voters in the C2DE social grade – made up of skilled and unskilled manual workers, pensioners, casual workers, and the unemployed – plumped for the Tories. Though Johnson’s victory and Labour’s defeat were dramatic, the process of class dealignment has been long in the making. James Tilley is a professor of politics at Oxford University and co-author of The New Politics of Class: The Political Exclusion of the British Working Class. spiked caught up with him to find out more.

spiked: How important was class to how people voted in the 20th century?

James Tilley: Very important. In Britain, class was one of the best indicators of how someone would vote in elections from 1945 to the 1990s. Large proportions of people with working-class occupations would vote for the Labour Party, large proportions of people with middle-class occupations would vote for the Conservative Party. And that was a constant rule of how electoral politics worked in Britain for at least 50 years after the war. Today, class essentially holds no importance in electoral politics. It’s not a good predictor any longer of how someone will vote. This change happened in some ways quite abruptly but also quite gradually.

This is, of course, completely separate from whether class matters and the general sense of how it might affect people’s lives. But in terms of how it affects people’s vote choices, there has been a big change.

Essentially, class voting declined in very rapid rates in the 1990s and 2000s. This coincides, perhaps not surprisingly, with the New Labour period and the transformation of the Labour Party. In this period, class is still an important factor, but nowhere near as important as it used to be.

But from 2015 onwards, there is another sharp decline, to the point where today, the party traditionally associated with the working class is actually less popular among the working class than the party traditionally associated with the middle class.

spiked: The subtitle of your book is ‘the exclusion of the working class’. Has there been an active process of shutting out the working class?

Tilley: Yes and no. I don’t think you can unequivocally say that is what happened. If you look at the first big abrupt change in the 1990s and early 2000s, when the Labour Party had transformed, there are aspects of this change that were deliberate. Blair, and the people in charge of the Labour Party after 1994, deliberately moved policy – economic policy, in particular – towards the centre.

There were some other changes which were deliberate, such as the language New Labour used, which was much less focused on mobilising the working class. I don’t think they were aiming to exclude the working class but they were aiming to attract more middle-class voters, which they were very successful in doing.

But there were also changes which Labour was not really in charge of. For example, the parliamentary party became a lot more middle class over this period, and that is partly about decisions within the party, but it is also about the kinds of people that were standing for parliament and putting themselves forward as candidates. There was no longer a pool of ex-union officials or miners, for instance, to draw on.

It’s all of those things combined at once that changed public perception of the Labour Party from a party for the working class to a party for the middle class. The policies changed, the personnel changed, the kind of language that politicians used and the membership changed – all these things combined together. It became really obvious at this point to voters that the party is just different to how it once was.

In the 2001 and 2005 elections, there was a really big increase in non-voting by people who have working-class occupations and low levels of education. That is really striking in a British context. Because in the 1980s, even in the early 1990s, there was really very little difference in turnout rates by class and education. In fact, in the 1960s, there were elections in which people in working-class occupations were more likely to turn out than people in some middle-class occupations.

By the middle of the 2000s, there was a substantial gap in turnout rates between middle-class and working-class people which never existed before. So when we are talking about political ‘exclusion’, we are talking about people reacting to the changes in the choices the parties are offering. If parties do not offer choices that you are interested in, then why bother voting or identifying with the party? That is, in a nutshell, the argument of the book.

spiked: What about the smaller parties?

Tilley: We talk a bit in the book about UKIP, which is an interesting case because I think that the perception of UKIP is that it mobilised working-class voters. In some senses, that’s true. If you look at UKIP’s vote when it was doing reasonably well, or even when it was just getting five per cent of the vote, people with working-class occupations were disproportionately more likely to vote for it.

But actually, the level of class voting for UKIP was never anywhere near as high as it used to be for Labour. UKIP had a much broader class coalition than you might initially think. Also, it didn’t necessarily mobilise non-voters. The people that voted for UKIP, in general, tended to be defectors from other parties.

The Liberal Democrats are interesting. They have historically been a middle-class party, representing what we call in our book the ‘new middle classes’, such as professional workers and people with degrees. We see this group of people being systematically more likely to vote for liberals way back into the 1960s. I think where you do see class voting today it is much more for the Liberal Democrats than it is for the two main parties.

spiked: Does class still matter or are we all middle class now, as Tony Blair once insisted?

Tilley: There are two separate elements to this: one is ‘does class still matter in my life?’. It is still the case that if you are a lorry driver you are going to earn less money than if you are a teacher. We can group people into the kinds of jobs which we associate with different social classes, and this is still highly predictive of people’s income, their job security, how likely they are to be employed, their health and the likelihood of their children going on to do different types of jobs. It would be insane to say that class was dead in that sense.

Classes are still quite predictive of how people will live their lives. It is still quite difficult to move from one class to another, even through the generations. If my parents have a certain kind of job, then chances are I am going to have that kind of job. This has not really changed very much since the war. Social mobility might have gone up or down a bit at times, but basically not much has changed.

In an objective sense, class is still a real phenomenon. But whether people see themselves in social classes is slightly different. Objective reality does not necessarily have to inform your perceptions. I think it’s a bit in the eye of the beholder. You can ask people, ‘Do you identify as part of a social class?’. Based on this question, most people do not think of themselves in class terms. However, if you then prompt them and say, ‘Do you identify as working class or middle class?’, pretty much everyone will then make a choice and say if they are working class or middle class, which might suggest that most people do think in class terms.

We have got reliable data on class identification going back to the 1960s. What you tend to find is there has been a small increase in the number of people identifying as middle class and a small decrease in the number of people identifying as working class. This is strange, because there has been a much bigger increase in the actual number of people in middle-class occupations, and there has been a big decrease in the number of people in working-class occupations. So class identity is lagging behind the actual changes in society.

Many people’s sense of class identity is not just about their economic circumstances. And there is a lot of evidence that is the case. It is very plausible that someone who describes themselves as working class might not have a working-class job. Perhaps their parents had working-class jobs. The current Labour leadership contenders all claim to have working-class credentials on the basis of their upbringing. That’s fine. This can be part of your class identity. But that is slightly different to what social scientists mean when we talk about class.

spiked: What other factors have taken Labour away from its working-class support base?

Tilley: Social-democratic parties, including Labour, not only have a cross-class coalition of voters, but also have to represent a coalition of different interest groups. Social-democratic parties tend to do very well among ethnic-minority voters and Labour is no exception to that. They tend to do well with younger voters and those dependent on social welfare. But these are not necessarily groups that have all that much in common with each other.

Stitching this coalition together is tricky compared to the past, when all these parties had to do was appeal to one group in society to win an election. Conservatives and Christian democrats have historically had to build broader coalitions, based on overarching identities, such as national identities or religious identities. The social-democratic coalition today is much more fragmented than it was. That is a systematic problem that Labour and other social-democratic parties are facing.

James Tilley was talking to Fraser Myers.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.