Stop apologising for the past

Labour’s promise of an inquiry into Britain’s imperial history is pointless.

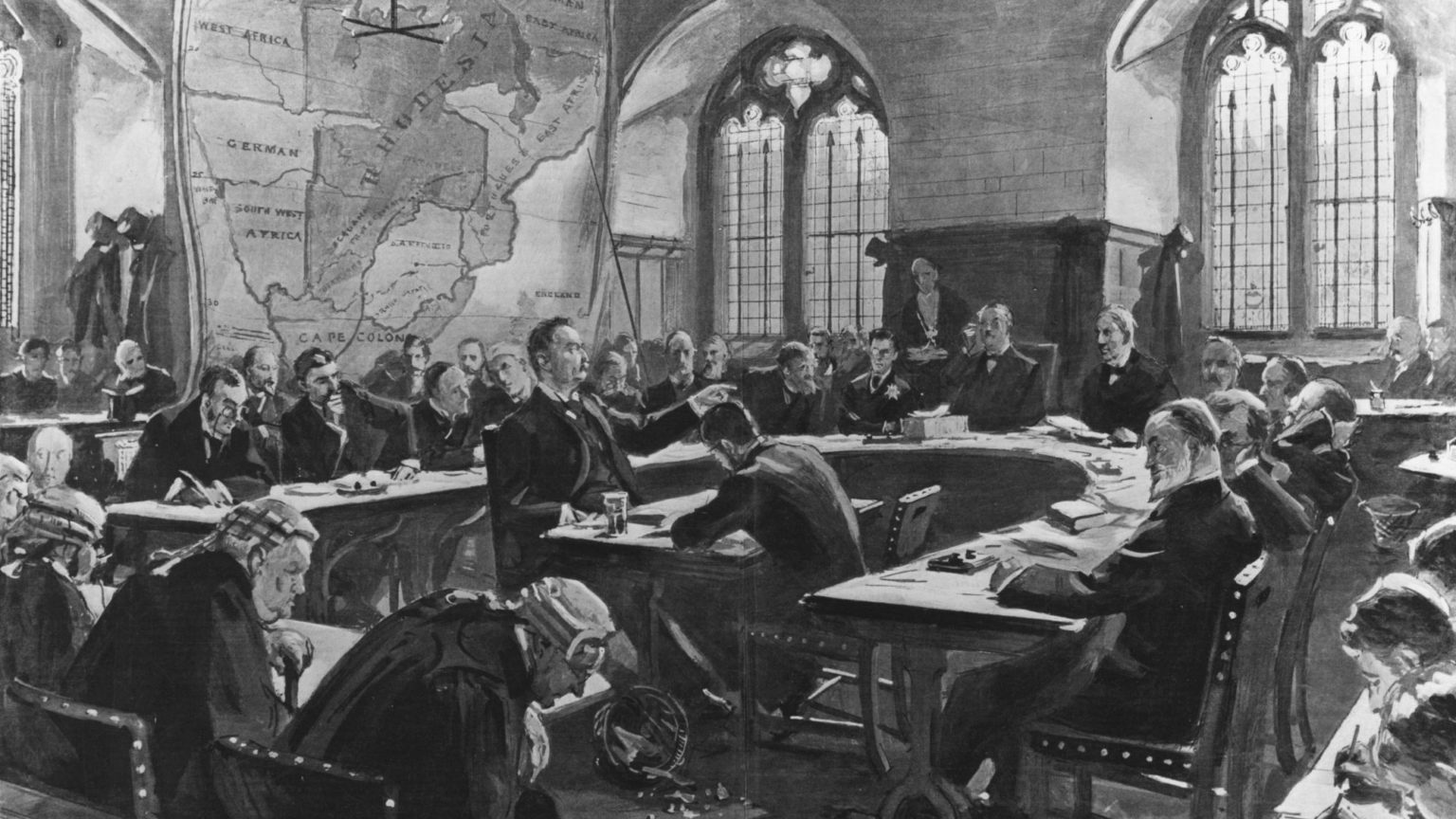

The Labour Party’s much-trailed manifesto is reported to include a promise to inaugurate an inquiry into ‘the legacies of British imperial rule’.

The backdrop to this proposal is a growing campaign to challenge traditional ideas about the virtues of the British Empire, and shine a new light upon the darker chapters – like the Bengal famine of 1943, which killed three million, or the torture and execution of Mau Mau fighters in Kenya’s struggle for independence.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has raised similar ideas before. Last year in Bristol he proposed a special Emancipation Education Trust to teach about slavery and Empire in schools.

The new proposal is not without precedent. Government inquiries into the Empire were commonplace in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the Colonial Office published the reports of colonial governors on a regular basis. Historians have been blessed with millions of pages of official reports put out by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office and raw records kept at the Public Records Office at Kew.

However, the thinking behind the Labour Party proposal is complicated. It perhaps springs from a recognition that the Labour Party in government has long been an enthusiastic champion of imperialism, from the Great War right through to the Iraq War of 2003 and beyond.

If, as many people believe, Labour is making this new proposal because it wants the country to come to a moral judgment about the British Empire, that raises significant problems.

Governments ought to make available as much of the historical record as is practicable. One of the significant complaints made against the Colonial Office is that they appear to have kept large amounts of material hidden. They destroyed a lot, too.

Historical knowledge is constantly being deepened and nuanced, and often significantly transformed. Historical inquiry is a valuable part of the way that a community relates to its past and its goals today.

When it comes to governments casting judgment on historical events, however, the value is more doubtful. The Labour proposal is part of a movement to pass a negative judgment on the history of the British Empire. There is good reason to criticise Britain’s imperial record, which is indeed steeped in oppression and cruelty. But the virtue of the British government making pronouncements about the past is less clear. In the case of most of the events in question, the conflicts are long since passed, and the protagonists dead.

For the British government today, to strike a moral position on governments of the past is an empty kind of gesture politics. In 1997, Tony Blair apologised for not doing enough to help Irish victims of the Potato Famine of 1847. But Tony Blair was in no position to do anything about the Potato Famine, since he wasn’t born for another century.

(It was poor history, too. The problem in 1847 was not that the British government did too little to stop the famine, but that British absentee landlords did too much to promote famine. Their predatory attitude to rents left their tenant farmers dependent on a single crop — the potato — while their other produce, including wheat and beef, continued to leave the country as a form of payment of rent to the landlords.)

This year, Britain’s high commissioner expressed his deep regrets for the Amritsar Massacre by British forces in India a century ago, in 1919.

These expressions of regret fail to satisfy because everyone can see that they are tailored to meet the needs of present-day statecraft, not to fix problems from the past. Just as the British governments of 1847 and 1919 defended their actions to silence criticism, the governments of 1997 and 2019 made expressions of regret to meet their policy goals today – principally to advance Britain’s claim to moral authority in the world.

Many Britons resent the apologetic attitude to the past. They think that the willingness of Labour Party politicians, Foreign Office diplomats and university lecturers to find fault with Britain’s military past is aimed at them. The hundreds of thousands who took part in Remembrance Day services are less interested in collecting evidence of war crimes and more in honouring the sacrifice of British servicemen. Their patriotism arises out of a common commitment to the country they live in.

Many of them suspect that the rewriting of the past is about making them feel guilty for Britain’s imperial record today. They hear the apologies as saying that they should have something to feel bad about or say sorry for. The point seems to be that, as British citizens, they were privileged and pampered at the expense of the colonies’ subjected peoples. Telling people who are themselves working hard to get by that they should be sorry about the past is just a way of putting them down.

It is perhaps an indication of the judgmental implications of the contemporary anti-colonial mood that many commentators and academics wrote of the result of the 2016 referendum as a malingering sickness of imperial nostalgia (see, for example, Fintan O’Toole’s book Heroic Failure). Leave voters struggled to understand this judgment, wondering how it was that these wise owls heard ‘bring back the Empire’ when they voted to leave the European Union.

No doubt people in the future will look back at us today and wonder at the things that we are doing wrongly. But sadly, we cannot tell what judgment the historians of the future will make of us. Will they condemn us for burning fossil fuels, or will they perhaps condemn us for encouraging children to undergo sex-change surgery? Only time will tell.

To imagine that the moral judgments we make today are the last word is to make the error of ‘presentism’. Just as we are astounded by the shocking things our forebears said, so too will our descendants be shocked by us.

In George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, the protagonist Winston Smith has a job rewriting past editions of the official newspaper to match the policy alignments of the present. The story is meant to shock us as a dishonest and philistine treatment of the truth. Britain’s record of imperial domination of hundreds of countries and peoples across the world cannot be expunged. Nor should we want it to be. A future Corbyn government could go through the motions of apologising for things that it did not do, but what would be the point of that?

James Heartfield is co-author of The Blood Stained Poppy, published by Zero Books. Order a copy here.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.