Long-read

Are we really over the Moon?

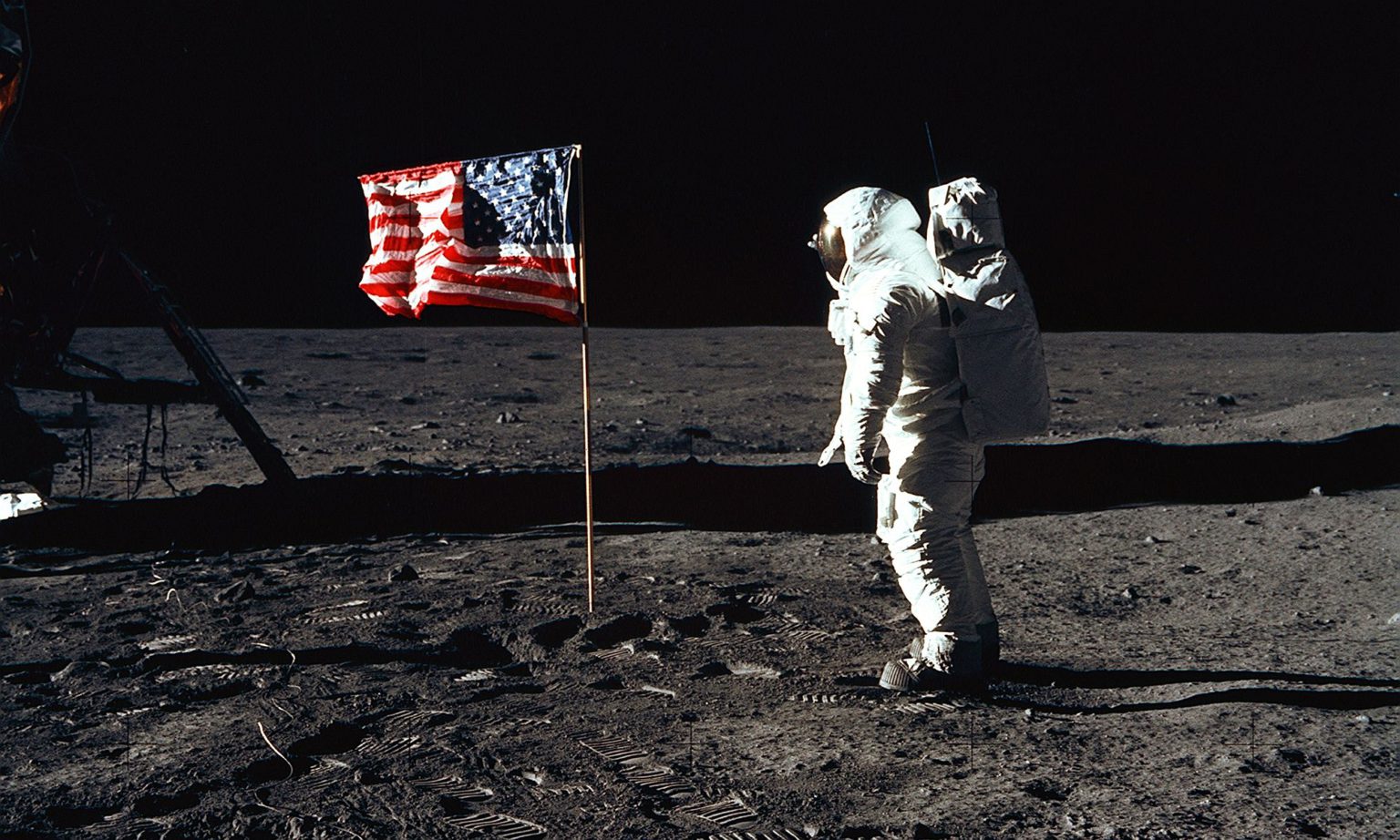

On the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing, that Promethean ambition can still inspire us.

It is now 50 years since America, in the form of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, succeeded in fulfilling President John F Kennedy’s challenge to ‘land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth’. Everyone knew that the challenges faced by all those involved were monumental. And few thought it possible. Yet, after countless failures, and even a tragic loss of life, NASA did it. And for that, the Moon landing rightly stands out as one of the most remarkable human achievements of all time.

For those of us who lived through it, the Moon landing was indeed a moment of genuine wonder and inspiration. Everyone remembers where they were on 20 July 1969. I recall excitedly looking at the Moon through a friend’s telescope in the naive hope of catching a glimpse of Neil Armstrong and ‘Buzz’ Aldrin bouncing on the lunar surface. What I did see was the splendid blinding brightness of a planetary satellite at which countless generations of humans before me had also stared, pondering their place in the universe. It is no exaggeration to say that in looking to the heavens that day, mankind was truly united, not only in the present, but with all past generations. It was, and remains, a unique moment in human history.

On the 50th anniversary of Armstrong’s small step on to the Moon, it is important to ask why, despite our risk-averse and misanthropic times, the landing of a man on the Moon still retains its wonder.

Whatever might be said to detract from the significance of the Moon landing – it was too expensive, it only happened because of the Cold War, and so on – it cannot alter the abiding fact that it happened. Its meaning is equally indelible: it shows just how wonderfully creative and courageous human beings can be.

When Armstrong descended the ladder from Eagle, the Apollo lunar module, and stood on the Moon, it was not just the start of a new adventure. It was also one of the most significant moments in a long journey that began when man first climbed down from the trees, stood on two legs, and freed up his upper limbs and, crucially, his hands – the tools that were to spark human consciousness. The Moon landing was the outcome of that human journey, a journey we have had to undertake in order to overcome the limits nature has imposed upon us.

All sentient beings on Earth, including mankind, experienced the centrality of the Sun to their lives, and could see the stars and the Moon at night. All were trapped by the temporal that the celestial world imposed on the Earth. But only for humans did looking to the heavens spark the quest to know their meaning. And that quest is what enabled us, unlike any other beings on Earth, to overcome the limits nature imposed on us, including developing the ability to fly, in order to escape the iron grip of Earth’s gravity.

From Ancient Greece onwards, man was aware of nature’s shortcomings – that mankind lacked certain attributes nature had given to other species. The myth of Prometheus, the early development of which can be found in Plato’s dialogue, Protagoras, set out to explain the special place man occupied in the natural world. While the gods had created humans and all the other animals, it was left to Prometheus (Forethinker) and his brother Epimetheus (Afterthinker) to give defining attributes to each species to ensure their survival. As no physical traits were left when the pair came to humans, Prometheus was forced to steal fire and other practical arts from the gods, which he gave to mankind.

The real insight of the Prometheus myth was the recognition that man, unlike the other creatures on Earth, could not rely on his biological makeup to survive. He had to take control of his destiny. He literally had to become the myth he had invented to explain his position in the world. He had to become a Prometheus. And this required understanding and knowledge – knowledge, for instance, of the gradual fathoming of causality in the again-and-again repetition of nature’s cycles. As the 18th-century German poet and thinker, Friedrich Schiller, put it: ‘With the animal and plant, Nature did not only specify their disposition, but she also carried these out herself. With man, however, she merely provided the disposition and left its execution up to him.’

The tragic irony of the Apollo programme was that in conquering space, man rediscovered limits on Earth

When Epimetheus was dishing out natural attributes of survival to all, he forgot to give man wings. Unlike birds and insects, no individual human being can fly by flapping his or her arms and legs, no matter how determined he or she may be. We do not have the size, strength or indeed the appendages to make this possible. But mankind has developed the ability to fly. We can fly faster and over longer distances than anything nature created. This took thousands of individuals dreaming, experimenting, taking risks, and pushing beyond the limits of their current knowledge to unlock the secrets that would allow mankind to reach for the stars. We are able to fly today as individuals because as a society we have developed the knowledge, over centuries, of the materials to manufacture aeroplanes; of the fuels to power them; of the means of communication to guide and control them; and of the science underpinning the laws of aerodynamics. A limit imposed by nature on man is now a freedom as commonplace as walking, and far more impressive than anything conjured up by nature itself. Overcoming this limit is what eventually allowed us to build crafts that could escape Earth’s gravity and, just as incredible, safely return their crew back home again.

The determination to give man wings is clearly relevant to the Moon landing. But equally important, and less discussed, was the role the heavens played in this same journey. It was no accident that the heavens were the laboratory of mankind’s earliest forays into science. Through this, they allowed man to take the first exploratory steps towards escaping nature’s prison, through the creation of human time. Early mankind was imprisoned by the tyranny of the Sun and the cycles of nature – the changing seasons, the waxing or waning Moon. Mankind lived by raising crops and herding animals. We were in thrall to the seasons, and knowing when to expect rain, snow, heat, cold. Daylight time, when men could work, was the only important time. Escaping the dictatorship of the Sun was a prerequisite of human time. It would mean finding a way to measure life on Earth on our terms, in universally uniform units. Only then could human action, for making and doing, be understood anywhere, anytime. Time was, in Plato’s phrase, ‘a moving image of eternity’. No wonder that measuring its course tantalised humans the world over.

Human time was only the starting point of humanity’s intimate relationship to the planets. Looking to the heavens at night – the time when man could not work – provoked man’s inquisitiveness and imagination. And repeated experience prompted speculation on how unseen forces emanating from the very depths of the heavens shaped the smallest everyday happenings on Earth. This led to a new type of prophecy – astrology – driven by the awareness of death and, therefore, the all-too-desperate eagerness for clues as to what the future holds. For all its false hypotheses, astrology’s willingness to believe the improbable enabled man to go beyond surface appearances and common sense. Astrology set man on a path towards science. The planets – unworldly but ever-present forces – led mankind out into the world of history, with all its uncertainty, unpredictability and constant change. Science enabled man to harness nature for human ends.

Given all this, there is surely nothing more human than man’s ambition to stand on the Moon. For the man on the Moon – striving, technological man – is Promethean man. And if mankind could land a man on the Moon, and could solve the huge number of problems that potentially blocked this aspiration, then mankind was capable of solving anything.

Fifty years later, this Promethean moment seems a long time ago. In his new book Apollo’s Legacy, the eminent space historian Roger Launius quotes Farouk El-Baz, one of the scientists intimately involved with the Apollo programme. He reveals that Apollo was ‘a singular goal… the end game. We knew that nothing like it ever happened in the past and behaved as if it would have no equal in the future.’ These were prophetic words. One of the most important and unexpected outcomes of the Apollo programme was that in going to the Moon, man discovered the vulnerability and fragility of his species’ spacecraft — namely, Earth.

On 19 December 1972, something happened that was to have longer-term consequences than the Moon landing itself. It was the day the Apollo programme came to an end. On board the returning Apollo 17 capsule were not just the last three astronauts to walk on the Moon, but a negative of a photograph of the whole Earth – later branded ‘the Blue Marble’ – which became the most reproduced image in human history.

Snapped by astronaut-geologist Harrison Schmitt as Apollo 17 accelerated away from Earth towards the Moon, Blue Marble showed, in stunning technicolour, the Earth upside down, with the continent of Antarctica sprawled over the top, and, below, the African land mass (the birthplace of homo sapiens) bowed downwards towards the cradle of civilisation in the Middle East. You could just about see southern Europe right at the bottom. Only four years separated Blue Marble from another profound Apollo picture – Earthrise, captured by Bill Anders on Christmas Eve, 1968. This showed the vibrant blue Earth floating in black space, juxtaposed against the brown-grey horizon of the Moon. The Apollo programme had brought spaceship Earth’s apparent fragility to the attention of the world. Space, if it began to serve any function at all, came to remind us how utterly small and insignificant we are, how vulnerable as a species we are, and how our lifeboat Earth required the reining in of man’s inflated ambitions. It needed nurturing, not science; protection, not Prometheus.

The tragic irony of the Apollo programme was that in conquering space, man rediscovered limits on Earth. The growth of environmental misanthropy dethroned man and presented him as the threat to the fragile spaceship, Earth. Ridiculous as it may seem, the Apollo programme helped to recast mankind as the Earth’s problem rather than its preeminent problem-solver.

The retreat into a culture of limits was a tragic but unexpected outcome of landing on the Moon. Once the cheering ended, a mood of uncertainty engulfed the planet. It marked a profound regression for human progress and the imagination that drove it. Instead of looking to the heavens, man now needed to gaze inwards. The new world of exploration was the self, the realm of emotions and feelings. Man may have escaped gravity by overcoming the limits nature had imposed upon him, but now he was limiting himself. Instead of space, we now sought safe spaces. The Cold War, which fueled the space race, was replaced by the Culture War, which fueled introspection.

It is ironic to think that the mobile phones we carry in our pockets have more computing power than all of NASA had back in 1969. We would not have these technologies without the Apollo programme. Next time you order an Uber, you should be thanking the US Air Force and the Apollo programme. The tragedy is that we are not using this awesome computing power to solve the huge challenges facing society today. Instead, we are tied to our screens as we narcissistically explore our inner worlds. Mankind appears to have stopped looking to the heavens in favour of looking down at social-media feeds.

So, what can we truly say 50 years after Neil Armstrong uttered those immortal lines as he stepped on to the surface of the Moon? Well, unfortunately, that he was wrong. It was not a small step for [a] man. It was indeed a giant leap for [a] man, but not for mankind. That is yet to come. The renewed space race and the talk of going back to the Moon and then on to Mars is so far just that: talk. It is a long way from the scale, drive and self-belief of 50 years ago. It will certainly take more than the efforts of billionaires like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson for a new durable giant leap into space. Flash-in-the-pan space tourism for the wealthy elite does not amount to the colonisation of Mars or giant cylinders orbiting the Sun.

The exploring zeal of our forefathers, whose goal was never just to reach somewhere new, but to colonise and control it – of which the Moon landing was a remarkable but temporary expression – is as far removed from human self-consciousness today as Mars is from Earth. How the most risk-averse, narcissistic elite in human history will conquer Mars requires not a big but a giant leap of imagination.

One can debate the significance of Armstrong’s words. But his words are less important than the deed itself. By stepping on to the Moon, and leaving that remarkable boot print in the Moon dust, Armstrong immortalised mankind’s eternal and noble quest to know more. It took human aspirations and technological prowess to another celestial entity, a permanent reminder that human beings are unique and wonderful – indeed, a reminder that while time, nature and life are transient, human consciousness and imagination are limitless.

Norman Lewis works on innovation networks and is a co-author of Big Potatoes: The London Manifesto for Innovation.

Picture by: Getty Images.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.