The liberal autocrat

Merkel’s rule has been defined by a disregard for democracy.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

‘As federal chancellor I bear the responsibility for the successful and the unsuccessful.’ So said Angela Merkel on Monday when she announced that she would give up the leadership of her party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and step down as German chancellor in 2021. Some foreign newspapers presented this as a ‘shock decision’. But within Germany, Merkel’s announcement was largely greeted with relief.

Merkel made her announcement after the CDU had yet again suffered heavy losses in a regional election, this time in the federal state of Hesse. It was the party’s third setback since last year’s General Election, in which the CDU returned its worst result since 1949, and the right-wing, anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD) surged to become the third biggest party.

In the run-up to the recent elections in Hesse, polls had been indicating an increasing unhappiness. In September, a YouGov poll revealed that 43 per cent of Germans wanted Merkel to leave office; 42 per cent wanted her to stay. This month, former finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble, one of Merkel’s staunchest allies, spoke of a sense of fatigue with her chancellorship.

After 13 years of uninterrupted rule, and 18 years as head of her party, the news of Merkel’s stepping down came as a shock to no one. Now all there is to do is reflect on what her leadership meant.

Most commentators – in Germany and abroad – agree that hers was an era of stability. ‘She was an anchor of stability in an ever more confusing world’, writes Holger Schmale in the Berliner Zeitung. A Bloomberg editorial says that ‘with the liberal order under threat’, Merkel has been a voice of moderation and moral steadiness.

Germany’s stability over the past 13 years did stick out as more and more European countries were struck by economic and political crisis. In Greece and Italy, numerous prime ministers have come and gone during Merkel’s tenure. Germany’s economy has been in a comparatively good state for many years. But many Germans don’t feel that they owe the relative stability of the past decade or so to Merkel.

Nor is an unchanging government a positive thing in itself. Otherwise we’d all opt for benign monarchs. Indeed, the seemingly endless Merkel era has been characterised by a lack of democratic choice and the inability of the mainstream parties to open up debates and consider alternative ways of dealing with political problems.

Most commentators consider Merkel’s decline as being linked to her decision to open the borders to Syrian refugees in 2015, over the heads of voters. But her problems began much earlier.

From the start, she benefited more from the weakness of the opposition rather than her own ability to convince voters. She became chancellor in 2005 in a snap election sparked by the internal problems of the then ruling SPD-Green government. She won with a margin of only one per cent.

At the time, many predicted that this uncharismatic politician, who was also the first woman and the first person from the former East Germany to be chancellor, wouldn’t survive for long. Being underestimated, some Merkel biographers say, was one of her advantages.

In 2009 she was re-elected with only 33.8 per cent of the vote. But it was only after the Euro crisis that her popularity seemed to soar. In 2013, she managed to win many votes and came out as the clear winner of the elections, with 41.5 per cent – largely, it seemed, due to her handling of the crisis.

But even then, Merkel’s great advantage was the weakness of the main opposition party – the SPD. If the Euro fails, Europe will fail, were Merkel’s famous words. The SPD, keen to present itself as being even more pro-EU than Merkel, supported her plans to offset the effects of the Euro crisis. In the summer of 2012, an overwhelming majority of parliamentarians approved the permanent Euro rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism, and a fiscal pact championed by Merkel.

‘We are voting “Yes” because Europe is more important than party political rivalries’, the leader of the SPD, Sigmar Gabriel, said at the time.

Merkel might stand for continuity, but her politics has also been characterised by a devaluation of democracy and open debate. While her success at the 2013 elections suggested many voters agreed with her handling of the Euro crisis, those who didn’t were denied an alternative – all the parties had backed her. ‘Whatever party the citizen chooses, he chooses more and more European integration’, wrote political scientist Philip Manow in 2012. In the same year, the German constitutional court rejected a petition signed by 37,000 people, demanding a popular referendum on the Euro rescue fund.

This ruling was very much in line with Merkel’s own views: she has repeatedly spoken out against popular referenda. ‘She has taken highly controversial decisions without ever really engaging in open debate’, writes Holger Schmale. He points out that in the many years of Merkel’s rule, there hasn’t even been one great speech, in which she truly addresses people’s concerns. Voter turnout at elections in 2009 and 2013 hit all-time lows – another phenomena of the Merkel era. And in the spring of 2013, the AfD was founded.

The last time Merkel appeared in any way dynamic was at the height of the refugee crisis in 2015, when she famously declared ‘we can manage’. But local communities felt increasingly as if they had been left alone to deal with the challenge of managing the influx of over a million refugees in one year. Unable to lead with any constructive proposals, Merkel appeared more and more aloof. She may have been named person of the year by Time in 2015, but by then many voters – particularly those in the more conservative areas of the east, where she originally came from – had begun turning away from her.

As the chancellor was seen taking selfies with refugees and drinking tea with George Clooney, when she was being lauded as the moral compass of the liberal world, many voters asked themselves where their place was in all of this. The resentment became even stronger. In 2016, the news that the AfD had swept away the CDU in Merkel’s own constituency in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern caused shockwaves.

No one knows what the next three years will bring. But for many, it comes as a relief that the end of Merkel’s rule is now in sight. It isn’t a shocking or traumatic event — it is a chance to renew German democracy.

Sabine Beppler-Spahl is head of the board of the liberal thinktank Freiblickinstitut e.V., which has published the Freedom Manifesto. She is also the organiser of the Berlin Salon.

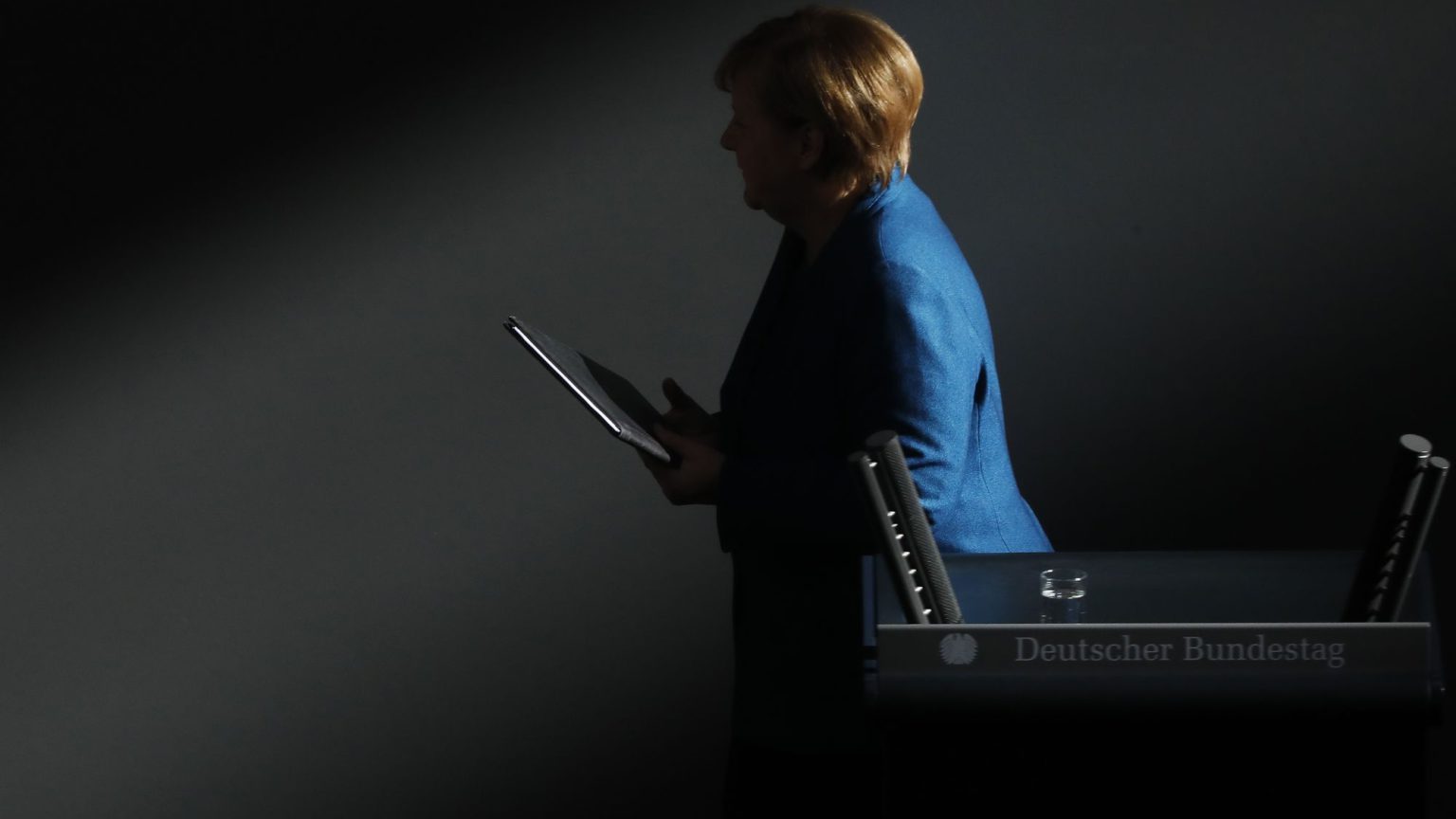

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.