Why demonising Iran is a dangerous game

Trump’s blundersome approach is escalating Israel-Iran tensions.

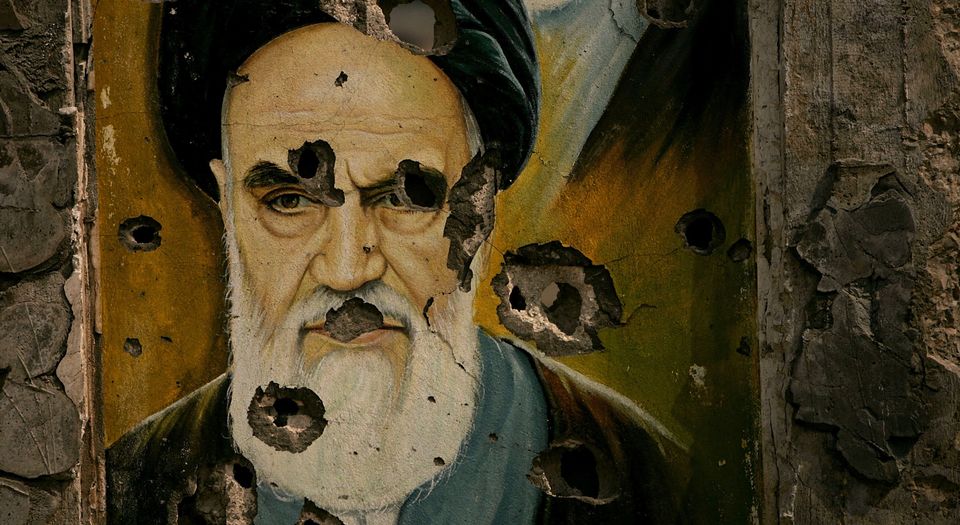

In a sense, it was not President Trump’s decision to rip up the Iran nuclear deal and impose sanctions, old and new, on Iran that was most troubling about last week’s announcement. Rather, it was the demonisation of Iran that accompanied and justified America’s withdrawal from the deal. It was the presentation of an illiberal theocratic regime as something more than it is; as something almost evil. A ‘murderous regime’, Trump called it, one that has enjoyed a ‘long reign of chaos and terror… export[ing] dangerous missiles, fuel[ling] conflicts across the Middle East, and support[ing] terrorist proxies and militias such as Hezbollah, Hamas, the Taliban and al-Qaeda’. The Iranian regime was being turned into something profoundly malign, the source of the Middle East’s unravelling, and, if it develops nuclear weapons, an undoubted threat to the entire world.

Trump’s demonisation of Iran is not just bombast; it carries with it an unstated implication. Because if Trump and his advisers really believe Iran is all those things, then the option cannot possibly be a new deal, as Trump himself indicated it could be in the same speech. After all, how can one strike a deal with a ‘murderous regime’, ‘the leading sponsor of terrorism’, without becoming morally tainted? No, if Iran is as near-enough evil as Trump implies, then the only option is the one preferred, in the US, by national security adviser John Bolton, US secretary of state Mike Pompeo, and Trump’s attornney, Rudy Giuliani, and in the Middle East by Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Saudi crown prince Mohammad Bin Salman: namely, regime change.

It is this unstated but extant possibility, over and above the ripping-up of the Iran deal, that threatens to inflame further conflict in the Middle East. It puts the Iranian regime on the defensive, and it emboldens Iran’s regional opponents, chiefly Saudi Arabia and Israel. Not that they want to intervene in Tehran themselves. But just the sense that the world’s only superpower would like to take down the Islamic Republic is enough to shift the dynamic, making Israeli or Saudi military moves more threatening to Iran, and Iranian counter-moves more threatening to Israel and the Sauds.

This ratcheting up of regional tensions has already begun to happen, as shown by the clashes between Palestinians, on Hamas-organised marches to the Gaza border fence, and Israeli security forces. Iran’s own response has, admittedly, been Janus-faced so far. To the European signatories of the deal, it has been conciliatory, with official talk of trying to stick with the deal minus the US. To the US and Israel, however, Iran has been aggressive. So last Wednesday night, Iranian forces launched a salvo of rockets against Israeli army positions in the Golan Heights, marking the most direct confrontation between Israel and Iran so far. And Mohammad Javad Zarif, the Iranian foreign minister, soon tweeted what looked like a promise to restart the Iranian nuclear-weapons programme. ‘The president of the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran has been tasked with taking all necessary steps in preparation for Iran to pursue industrial-scale enrichment’, he wrote — ‘without any restrictions [and] using the results of the latest research and development of Iran’s brave nuclear scientists’.

And Israel responded in kind, launching its largest series of airstrikes on Syria since 1974. A response that the Syrian government said marked a new phase in the conflict, which would warrant retaliatory action. An Iranian cleric added his two penneth, warning that Tel Aviv or Haifa would be in danger if Israel did ‘anything foolish’.

A war is unlikely, however, despite some of the more excitable headlines. Open conflict is not in Israel’s, Iran’s or Saudi Arabia’s strategic interests. Iran is too strong in Syria and Iraq, and too important to those respective states in their internal battles with Islamist insurgencies, to be allowed to be rolled out. But Iran is also too weak, in terms of finance and domestic political support, to extend and expand its influence in Iraq and Syria and beyond. Likewise, Israel is much too strong to be defeated militarily, but too weak to sustain a war with Iran. Its recent experience in the ill-fated Lebanese war in 2006, which failed to halt the consolidation and rise of Iranian-backed militia Hezbollah, is testament to its shortcomings. In short, no state is weak enough to be defeated, or strong enough to win.

Then there are the international factors. Iran still wants to retain some semblance of accord with Europe. US sanctions will inhibit the ability of non-US banks and businesses to deal with Iran, but as it stands, even without US involvement, Iran is still far less politically and economically isolated than it was before 2015. To pursue conflict openly in the Middle East would risk a return to complete isolation from the developed world.

And then there is Russia, which is hovering neutrally on the sidelines of the Iran-Israel scuffles. It has backed the Iranian regime in the past, especially to the extent that Iran has helped quieten the Islamist threat, be it ISIS or various al-Qaeda spin-offs. But Russia has also been supportive of Israel. Its official silence on Israel’s attacks on Iranian positions in Syria was telling, as was Netanyahu’s trip to see President Putin last week. But any move that would threaten the hard-won gains of Assad in Syria would surely prompt a more forthright and no doubt military response from Russia.

So the Middle East is riven with tension, which at points has erupted into open conflict – albeit, for the most part, confined to those territories rendered semi-stateless thanks to Western intervention, be it Iraq, Yemen or Syria. But such is the balance of forces that there is little to be gained, and much to be lost, from any attempt to pursue conflict further.

But that does not account for the Trump factor. He and his team do not seem to be concerned about any balance of forces, or strategic calculations. Rather, like their predecessors in power, they seem all too ready to conceive of the Middle East in simple-minded Manichaean terms, with evil power-holders only needing to be replaced for peace and goodwill to break out, and democracy to flourish. For the two Bushes and Bill Clinton, Iraq and Saddam Hussein were the source of evil, with Iran playing the role of pantomime villain, complete with its ‘Death to the USA’ marches. For Trump, or at least for those whispering sweet praise in his ear, Iraq has now been replaced by Iran as the No1 baddie. The object of US enmity may change, but the dangerous, destabilising course of action remains the same.

Trump may of course do something entirely unexpected. He seems to be as keen on withdrawing the US from its Middle Eastern adventures as he is on pushing America’s allies and proxies further into combat. When a leader is as vain and whimsical as Trump is, decisions are made on the hoof, dependent on how he feels, on who or what has flattered his esteem and who or what has disturbed it. Today’s interventionist could be tomorrow’s pacifist. But with US allies in the Middle East happy to dream of regime change in Iran, and the US seemingly happy not to disabuse them of such dreams, there is always a chance that this anti-Iranian alliance could blunder into a war to which none is fully committed.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture: Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.