If Nietzsche were alive today…

Patrick West’s new book casts a searching, Nietzschean eye over the present.

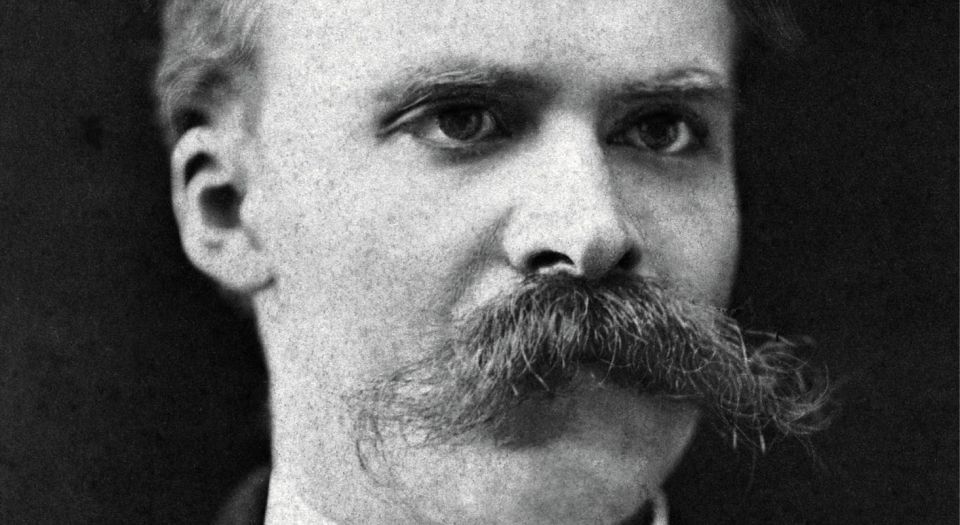

Friedrich Nietzsche is an ambiguous figure today. Fragments of this infamous philosopher are all around us. He invented the word ‘superman’; his pronouncements on the nature of good and evil, on self-empowerment and overcoming through struggle, are echoed throughout popular culture, from Harry Potter to Kanye West; and an entire self-help industry, enthusing about the ‘gift of failure’ and churning out books with titles like Feel The Fear And Do It Anyway, is heavily indebted to Nietzsche.

Yet when named directly, Nietzsche remains controversial. He is accused by some of being a proto-Nazi, and he is considered by others to be responsible for two world wars. While those claims are overblown, there is little doubt that Nietzsche’s fierce criticism of an emerging mass, democratic society put him firmly on the side of anti-democracy. So surely Nietzsche, for all his influence on our intellectual and cultural development, is a thinker best understood in his context, rather than someone whose ideas we would wish to revive today?

Perhaps not. In his new book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, Patrick West, a columnist for spiked, rejects the idea of contextualising Nietzsche in order to explain away the less palatable aspects of his thought. In fact, West is not really interested in judging Nietzsche. Quite the opposite; he asks Nietzsche to judge us. And it is an incredibly rewarding move, because while Nietzsche’s thought offers few concrete solutions, it does offer a tonic against all manner of contemporary social ills.

Take identity politics and all its attendant narcissism and navel-gazing. Nietzsche attacked this kind of thinking at its root, firmly rejecting any suggestion that national, cultural, racial, religious, gender or sexual identities should be recognised, let alone respected. For Nietzsche, West argues, labels imprison us. ‘Life is concerned with forever becoming, for striving to go beyond oneself’, writes Nietzsche. Indeed, his philosophy of the superman, outlined in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, concerns the individual who goes beyond himself: ‘Man is something that should be overcome’, says the titular Zarathustra. ‘What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal.’ There could be no sincere true self to whom one’s identity must be true, for a fixed, true self does not exist. Introspection is the enemy of achievement: ‘Acknowledge yourself through action, not observation.’ Nietzsche would urge us not to be true to ourselves, but to rebel against ourselves.

The modern cult of ‘safe spaces’ would also grate against Nietzsche’s exhortation to ‘live dangerously’. We live in a culture where words are deemed to wound, all manner of subject matter is deemed ‘triggering’, and mere thought is considered dangerous. Nietzsche’s approach to ideas could not be more different: ‘Build your cities on the slopes of Vesuvius! Send your ships into uncharted seas! Live at war with your peers and yourselves! Be robbers and conquerors as long as you cannot be rulers and possessors, you seekers of knowledge!’

West tells us that Nietzsche wouldn’t be surprised that much of today’s assault on free speech and free thought comes from universities. In his day, he rallied against the ‘state philosophers’ of academia, as he characterised his colleagues. His famous adage of ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’, while not true in a literal, physical sense, is most relevant to training our intellectual and moral muscles. In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche writes that ‘one must never have spared oneself; harshness must be among one’s habits, if one is to be cheerful and happy among nothing but hard truths’.

Nor would Nietzsche have much time for today’s keyboard warriors on social media. Although, as West explains, the term ‘virtue signalling’ was only coined in 2015, Nietzsche would immediately recognise ‘that Pharisee tactic of the sick, the loud gesture’, clogging up our newsfeeds. Such forms of public emoting represent a surrender to our baser, more animalistic urges, where Nietzsche would counsel us to stick to ‘rigorous reflection, compression, coldness, plainness… restraint of feeling and taciturnity’. The flipside of public virtue is righteous indignation, mostly found today in the form of Twitterstorms, which Nietzsche would equally decry as a product of the herd instinct, in all its ‘lustful greed, bitter envy, sour vindictiveness, mob pride’.

When it comes to examining Nietzsche in his own time, Get Over Yourself provides some much needed mythbusting, particularly on the Nazi question. As West points out, Nietzsche deplored anti-Semitism and German nationalism. But this is no rehabilitation of Nietzsche – West makes no attempt, for instance, to excuse Nietzsche’s virulent misogyny. Likewise, there is no whitewashing of Nietzsche’s own narcissism, or even megalomania, best expressed in the chapter headings of Ecce Homo: ‘Why I Am So Wise’; ‘Why I Am So Clever’; and ‘Why I Write Such Excellent Books’. West has no desire to turn us into worshippers of Nietzsche, which is just as well given the man himself would have despised even his own disciples. For West, Nietzsche should be embraced if only to be overcome.

What Get Over Yourself makes clear is that no matter how violently one may disagree with Nietzsche’s pronouncements and conclusions, his exhortations to question everything, to strive to go beyond oneself, to be fearless in thought and deed remain vital in an era of staid conformism, righteous indignation and self-regard.

Fraser Myers is a producer at WORLDbytes.

Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche for Our Times, by Patrick West, is published by Societas. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.