Bowie: his life, times and transformations

He kept us guessing to the very end.

David Bowie is dead. Just two days after his 69th birthday and the release of Blackstar, his 25th studio album. Rumours of his ill-health had been going around for some time, following his heart surgery in 2004 and his refusal to make any public appearances to promote his previous album, The Next Day (2013). It turns out that he had been suffering from cancer for the past 18 months.

His reclusiveness at the time of The Next Day, his first album in 10 years, was just another ingenious tactical move in the career of pop music’s greatest media manipulator. That a veteran musician like Bowie could attain such mystique, not only at such a late point in his career but in an era when celebrities are expected to share every minor detail of their lives, is truly astonishing. If he hadn’t become so seriously ill, I’m convinced he would have returned to live performance. He would have lulled us into thinking that he’d never perform again, so he could exploit it for all it was worth.

He has always kept his fans guessing. His constant shape-shifting, his numerous alter egos, made the ‘real’ David Bowie hard to pin down. There was always so much more to Bowie than the music.

His interest in music originated during his childhood in Bromley, in the suburbs of south London. Following an interest in jazz and rock’n’roll, Bowie – then David Jones – learned to play the saxophone, with the ambition of one day joining Little Richard’s band. It was also during this time that other parts of the Bowie myth were forged, such as the schoolyard fight which left his left eye permanently damaged, and the popular theory that, due to his half-brother being sectioned, his music is plagued by his fear of going insane.

After an unsuccessful debut album in 1967, inspired by the music-hall stylings of Anthony Newley and Tommy Steele, he had his first hit two years later with the extraordinary ‘Space Oddity’. Introducing the space imagery he would later expand upon, the song, with a powerful mix of folk and psychedelia, tells the story of astronaut Major Tom, the first of his many alter egos. He would not have another hit single for another three years, but he continued to reinvent himself, even if nobody noticed, releasing the hard-rocking The Man Who Sold the World album in 1970.

Bowie released his first masterpiece in 1971 with Hunky Dory. It’s a singer-songwriter’s album, the lyrics densely packed with allusions to everything from Aleister Crowley to the Velvet Underground, and fitted to gorgeous arrangements of piano and strings. Highlights include ‘Changes’, a manifesto for his entire career if ever there was one, and the highly charged balladry of ‘Life on Mars’, one of his all-time greats.

Hunky Dory was more or less ignored upon release, but charted after the release of his follow-up and breakthrough album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. This glam-rock concept album follows an alien-like messiah named Ziggy Stardust in an apocalyptic world. Every track is a classic, starting with a song about the end of the world (‘Five Years’) and ending with ‘Rock’n’Roll Suicide’ – between which there is the sublime ‘Starman’ and ‘Moonage Daydream’.

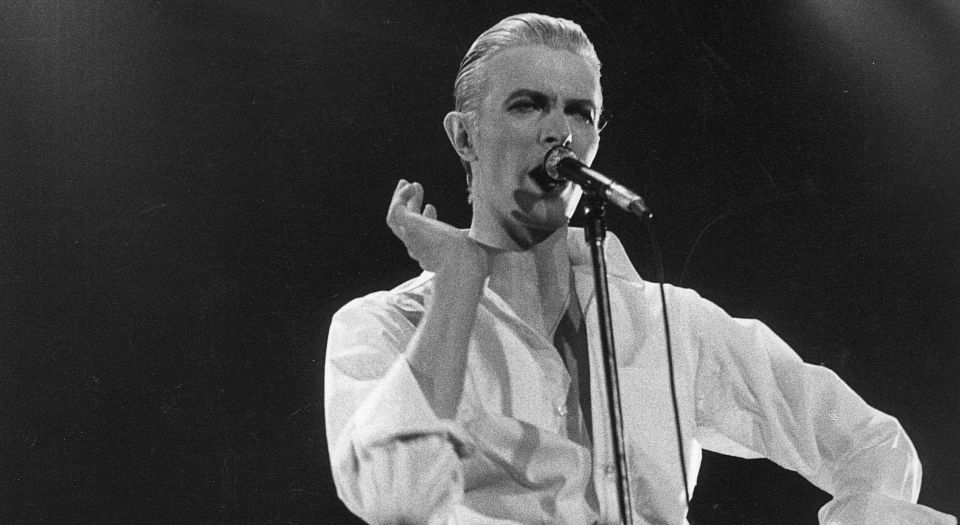

Of course, the appeal of Ziggy Stardust was far more than the extraordinary music. Bowie’s performance of ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops was his most iconic – it was when the public was first introduced to his genius. With blazing red hair, made-up face and multicoloured jump suit, he looked like nothing audiences had ever seen before. Ziggy was indeed like something from outer space.

Bowie has fans of all ages, but his music had the most powerful effect on those who were teenagers at the time of his rise. The way he pursued his career gave hope to confused adolescents the world over, and gave them a model of how to live their lives. He showed it was okay to be different, that we have the agency to make changes in our lives, and that, as he implied with his countless references to other artforms, we should be curious about as many things in life as possible.

Ziggy Stardust and its wild companion piece Aladdin Sane would have been enough to cement his legendary status – but he was just getting started. In 1973, he shockingly killed off Ziggy Stardust, announcing at the last gig of the Aladdin Sane tour that it was the last he was ever going to perform. His backing band were promptly dismissed, and he ditched the image which had made him famous.

This was followed by the transitional Diamond Dogs, a dystopian concept record featuring the hit single ‘Rebel Rebel’. Then Bowie underwent his first reinvention since hitting it big, with the album Young Americans. He swapped his kimonos and red mullet for Puerto Rican suits and a James Dean quiff, and began performing soul music – ‘white plastic soul’, he called it – with a backing band of black American musicians. This dramatic transformation paid off, giving Bowie his commercial breakthrough in the US and scoring a number-one hit with ‘Fame’, a funk jam co-written by John Lennon.

Bowie has often been called the chameleon of rock, but this is a major fallacy. A chameleon changes to fit in with its surroundings, which is the exact opposite of what he did. He always stood out from the crowd, completely at odds with whatever time he found himself in. He didn’t spoon-feed his fans with hackneyed takes on the latest trends; he respected their intelligence and expected them to keep up with his endless transformations.

Bowie rejected the clichés of ‘authentic’ rock, the idea that ‘real’ music could only come from plainly dressed musicians singing of ‘real’ working-class life. He expressed immense emotions, isolation being his most recurring theme. He performed impressionistic lyrics set in fantastical worlds – and dressed to match. Though he was in many ways a detached, ironic artist who revelled in artifice, that doesn’t undermine the sincere emotions he expressed.

His popularity in the US during the mid-Seventies was marred by his cocaine addiction – an addiction so intense he couldn’t even remember making Station to Station, a fascinating record of six long songs centred around the Thin White Duke, another Bowie guise somewhat like the emcee from Cabaret.

The Thin White Duke would prove to be his last alter ego. Hitting rock bottom, he moved from LA to Berlin, shunning publicity and getting clean with fellow addict and rock star Iggy Pop. During this time, he recorded the extraordinary Berlin Trilogy, three albums (Low, Heroes, and Lodger) featuring fragmented song structures and ambient instrumentals, made in collaboration with Brian Eno. They expressed a range of emotions, from the bleakness of songs like ‘Sound and Vision’ to the hope and romance of the title track of ‘Heroes’ – surely Bowie’s greatest song.

After his 1980s album Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps), he never regained the quality of his material from his golden years. Still, he remained constantly fascinating and immensely popular, from the laziness of his blockbuster success in the mid-Eighties to his bizarre industrial/drum’n’bass genre excursions in the Nineties to his eccentric film career – there is an entire generation of fans who know and love Bowie best for playing Jareth the Goblin King in Labyrinth.

After his biggest ever tour and then major heart surgery, he disappeared from the limelight in the mid-2000s, never to perform live again. That didn’t stop him from having a number-one album with The Next Day, and a hit single with ‘Where Are We Now?’ – his first Top 10 hit in the UK for some 20 years. Right up to the end, Bowie was still keeping us guessing.

His new album, Blackstar, was released just last week. Fans will now scrutinise the album, looking for hints of his awareness of his own mortality. The music continues to be dense, rich, expressive, surprising and open to interpretation. After choosing to remain silent for the last decade, he will now never speak again. There are so many mysteries of this great artist we will never get to the bottom of. And that’s just how Bowie would have wanted it.

Christian Butler is a writer and musician based in London.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.