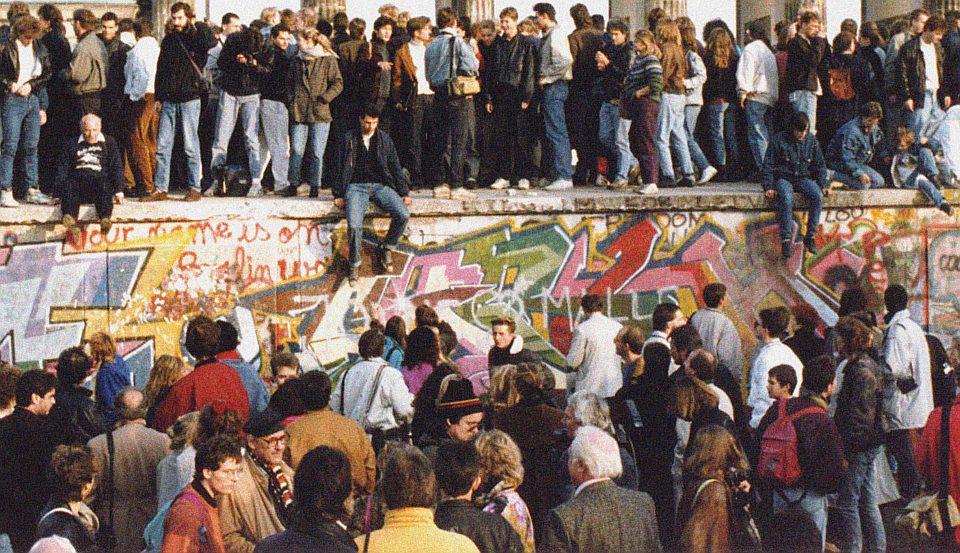

25 years after the Berlin Wall fell, a Culture Wall has replaced it

Why the fall of the wall did not herald a new golden age of politics.

As Germany celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Mikhail Gorbachev spoiled it all by reminding everyone that the world is still far from at ease with itself. The former Soviet leader warned that we are on ‘the brink of a new world war’ and he criticised the Western powers for cultivating a climate of conflict and tension in their dealings with post-Soviet Russia. For once, this old Soviet politician was almost right. Twenty-five years after the demise of the Berlin Wall, the global situation looks more uncertain and unpredictable than it did during the Cold War, when the world was frozen into two super blocs. However, despite the seeming reappearance of diplomatic clashing between the US and Russia, the world today has little in common with the Cold War moment of the post-Second World War era.

It is worth noting that, at the time, the collapse of the Berlin Wall was looked upon by most of the major powers as, at best, a mixed blessing. The division of Germany provided the foundation for the postwar global balance of power. This Cold War balance helped to minimise the conflict of interests between East and West. Indeed, the Cold War was underpinned by an understanding which allowed the US to maintain hegemony over the capitalist world and which gave the Soviet Union a regional sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. In retrospect, what was remarkable about the Cold War was the ability of most of the major players to manage their conflict. Despite the aggressive rhetoric of this era, the Cold War was a period of relative peace between hostile geopolitical blocs. The bloody upheavals and wars occurred not in Europe, America or Russia, but in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, and were either directly or indirectly a response to the experience of Western colonialism.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent disintegration of the Soviet Union was greeted by numerous Western observers as a vindication of their way of life. At least superficially, it seemed to many that the post-Cold War era would herald a new Golden Age of global capitalism. Yet once the Berlin Wall came down, and the Soviet Union followed it on to the scrapheap of history, ending the Cold War, the Western elites were faced with some fundamental questions that they had tried to evade for so long. The big question of what Western society stands for could no longer be answered by the statement: ‘We are defined by our hostility to Communism.’

The Soviet bloc imploded from within. The superficiality of its ideological outlook was exposed in the fact that it could not inspire or motivate a significant number of its own citizens. The West did not face any serious ideological competition towards the end of the Cold War – the swift demise of the Soviet bloc indicated that the West was very much kicking at an open door.

Paradoxically, Western societies were not intellectually or politically prepared for the post-Cold War era. Previously, Western societies could avoid the problem of spelling out what they stood for by appealing to the need to fight Communism. The Soviet Union and its very bad reputation served as the best argument for the Western way of life. The negative example of the Soviet way of life helped Western governments to dodge the question of what they really stood for. Liberalism itself, particularly in the form of so-called neoliberalism, remained an intellectually underdeveloped outlook and possessed relatively limited cultural support even in the West.

The Nobel Prize-winning liberal economist, Milton Friedman, was in no doubt that liberalism did not actually conquer its ideological opponents. He recognised that by the late 1970s support for the free market and capitalism had won out against the opponents of these systems; but he also knew that the shift in public opinion in his direction was more a consequence of the failures of state socialism than it was evidence of the compelling force of the ideals of liberalism. He insisted that the ‘change in the climate of opinion was produced by experience, not by theory or philosophy’. After summarising the numerous setbacks suffered by advocates of big government and the welfare state, he asserted that it was ‘these phenomena, not the persuasiveness of the ideas expressed in books dealing with principles’, that explained the ‘transition from the overwhelming defeat of Barry Goldwater in 1964 to the overwhelming victory of Ronald Reagan – two men with essentially the same programme and the same message’. In other words, the success of liberal economics was contingent on the failures of its opponents.

The end of the Cold War coincided with the erosion of the master narratives of modernity. The absence of any ‘overarching’ ideological project, and the general tendency towards the depoliticisation of public life, was most coherently expressed in the Third Way projects of the 1990s.

In effect, the tensions and conflicts immanent in capitalist societies had ceased, at least temporarily, to be fought on the battlefield of politics. This development was most vividly expressed in the phrase Margaret Thatcher hurled at her detractors: ‘TINA’ – ‘There is no alternative’. By the 1990s, very few people needed to be reminded that TINA had acquired a life of its own and was now widely accepted. As Perry Anderson, one of Britain’s leading leftist intellectuals, argued in 2000: ‘For the first time since the Reformation, there are no longer any significant oppositions – that is, systematic outlooks.’

Yet the rhetoric of TINA – which continues to influence public life to this day – does not provide the political establishment with an ethos that might inspire public support and endow the establishment’s actions and policies with authority and legitimacy. The depoliticisation of public life that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall has encouraged public institutions to embrace a narrowly technocratic and opportunistic modus operandi. The estrangement of policymakers from principles and foundational values has made them vulnerable to short-termist, often arbitrary influences. The power of these corrosive trends explains the very poor quality of political leadership and policymaking in Western societies today. Governments now find it difficult to elaborate any norms, values or policies through which they might express national interests, or even just their own party’s interests. The most extreme manifestation of this incoherent form of policymaking can be seen in the realm of foreign affairs. Western military and diplomatic interventions in Libya, Syria, Iraq and Ukraine serve no geopolitical purpose; rather, these are self-destructive policies conducted by political elites that lack an understanding of geopolitical interests and any sense of clarity about the workings of the world. The recently published report Dangerous Brinkmanship, which argued that close military encounters between Russia and the West have escalated to Cold War levels, with 40 dangerous or sensitive incidents recorded in the past eight months alone, is evidence of just that: irresponsible brinkmanship. As was the case in recent interventions in Libya and Syria, these are provocations without regard for consequences. This pattern stands in sharp contrast to the carefully calibrated behaviour of hostile blocs during the Cold War.

Our post-Berlin Wall, depoliticised era has encouraged political leaders to behave in a way that feels extraordinarily disconnected from the real problems facing the global community. The West’s escalation of the war of words against Russia and the application of diplomatic pressure on the Putin regime is a good example of the kind of immature policymaking that threatens to unleash instability today. It is almost as if a nostalgia for the certainties of the Cold War drives NATO countries to confront Russia in this way. However, contrary to appearances, the world does not face a new Cold War. With the rise of China and India, the development of new economies in Latin America, and the rise of radical Islam, the world can no longer be divided up into two hostile ideological blocs.

But just because there is no prospect of a return to the Cold War, that does not mean society and international affairs have been spared bitter conflict and disputes. On the contrary, the depoliticisation of public life has coincided with the emergence of conflict in the most unexpected places. What has happened is that in recent years the depoliticisation of public life has led to the politicisation of other areas of social experience, particularly morality and culture.

Disputes over lifestyle, family life, sexual orientation and the nature of community life are no longer confined to the domestic sphere. The Culture Wars have become internationalised. Muslim jihadists are not just fighting with bombs. They are directly assaulting Western liberal values and denouncing them as immoral. For his part, Putin has sought to assume the mantle of the global leader fighting for traditionalism and the Christian way of life. In turn, Western diplomats have criticised Russia for its patriarchal and sexist culture.

Some might conclude that the new international conflict over values is relatively benign compared to the old ideological wars that led to the division of Germany and the rise of the Berlin Wall. But this isn’t true. Conflicts over lifestyles and values are difficult to manage because they touch on basic moral issues such as good and evil. Morally charged conflicts are rarely susceptible to compromise and often lead to a breakdown in communication. Which is why in the current era, the displacement of ideology by the politicisation of values has been expressed in the shift from a Cold War to a Culture War. Hopefully, the divisions that were once symbolised by the old Berlin Wall will not reappear in the form of an equally depressing Culture Wall.

Frank Furedi’s First World War: Still No End in Sight is published by Bloomsbury. (Order this book from Amazon (UK).)

Picture by: PA images.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.