Orwell’s war on the ‘smelly little orthodoxies’ of left and right

Into the heart of the rebellious, liberty-loving, contrary heart of George Orwell.

In a ‘horrible and squalid back alley’ in Wigan on 15 February 1936, a chance encounter changed George Orwell’s life forever. He’d just begun his diary for his book The Road to Wigan Pier a fortnight before. Here is how he described the encounter in his notes: ‘Saw a woman, youngish but very pale and with the usual draggled exhausted look, kneeling by the gutter outside a house and poking a stick up the leaden waste pipe, which was blocked. I thought how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling in a gutter in a back alley in Wigan, in the bitter cold, prodding a stick up a blocked drain. At that moment she looked up and caught my eye, and her expression was as desolate as I have ever seen; it struck me that she was thinking just the same as I was.’

At the risk of some repetition, it is worth looking at Orwell’s treatment of the same moment in his finished book, especially as the writer, an old Etonian called Eric Blair, was often accused of being snobbish towards the working class with his descriptions of ‘labyrinthine slums and dark back kitchens with ageing people creeping round and round them like black beetles’. In the book the location has changed; Orwell is now sitting comfortably on a train leaving the depression-hit north of England and heading south.

‘As we moved slowly through the outskirts of the town we passed row after row of little grey slum houses running at right angles to the embankment’, he wrote. ‘At the back of one of the houses a young woman was kneeling on the stones, poking a stick up the leaden waste pipe which ran from the sink inside and which I suppose was blocked. I had time to see everything about her – her sacking apron, her clumsy clogs, her arms reddened by the cold. She looked up as the train passed, and I was almost near enough to catch her eye. She had a round pale face, the usual exhausted face of the slum girl who is 25 and looks 40, thanks to miscarriages and drudgery; and it wore, for the second in which I saw it, the most desolate, hopeless expression I have ever seen. It struck me then that we are mistaken when we say that “It isn’t the same for them as it would be for us”, and that people bred in the slums can imagine nothing but the slums. For what I saw in her face was not the ignorant suffering of an animal. She knew well enough what was happening to her – understood as well as I did how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling there in the bitter cold, on the slimy stones of a slum backyard, poking a stick up a foul drainpipe.’

This is a remarkable piece of writing, born of what was clearly a revelatory moment in that Wigan back alley. Orwell emphasises the distance between two very different, unequal people. On a warm train, with an upholstered seat, a published, public-school-educated author is on his way back to his comfortable world of publishers and left-wing literati. In a gutter, the woman kneels and, in the glance of an eye, as the train takes Orwell away, we understand what inequality really is. Equality is, as Orwell makes self-evident, the universal knowledge that a circumscribed life, the ‘dreadful destiny’ of existence in a 1930s industrial slum, flies in the face of what make us human, which is our refusal to bow to fate. At this moment, captured in an instant, all life, high or low, recoils at a fate forced by the circumstances of poverty. To be alive and in touch with the living is to feel the truth of this connection, transformed from a diary entry into great literature. This passage in Orwell’s first political book, The Road to Wigan Pier, is, I am convinced, the key to understanding the man, the twentieth century’s greatest British writer.

Within the year, on Boxing Day 1936, Orwell was in Spain at the height of the civil war, joining up to fight with anarchist and anti-Stalinist Marxist militia. Again, a chance encounter looms large in the opening pages of his book Homage to Catalonia, as Orwell, who has just signed up to the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista (POUM) militia, meets a young Italian fighter. ‘As we went out he stepped across the room and gripped my hand very hard. Queer the affection you can feel for a stranger! It was as though his spirit and mine had momentarily succeeded in bridging the gulf of language and tradition and meeting in utter intimacy’, he wrote. The meeting, where just six words were exchanged, later became a poem. ‘The thing that I saw in your face / No power can disinherit / No bomb that ever burst / Shatters the crystal spirit’, he wrote in ‘The Italian soldier shook my hand’ (1939).

Orwell, or rather Blair, was of the British upper class, but he could clearly see that human equality was a fact. It transcended class and nationality, and was palpable even in the briefest of encounters between people. It was the ‘crystal spirit’ that had bought a young Italian, and Orwell, to fight for democracy in Spain, just as it was the same human quality that made life in a slum unbearable. Equality for Orwell was not a merely a measure or a statistic; it was a quality that all living humans have, a resistance to fate even at its most blind.

These two encounters also reveal a man with a deep belief in the character and qualities of living humans, something that Robert Colls understands in his excellent ‘intellectual biography’ of Orwell. No book about Orwell can be perfect; the man was too contradictory, too contrarian and too bloody minded to be an easy study. But Colls (with some limitations) really gets it. Orwell refused ideology in a century defined by it, and that was his strength and brilliance. Setting out his stall, Colls, a professor of Cultural History at De Montfort University, puts his finger on why Orwell despised ideology as a ‘form of abstract knowledge which, in order to support a particular tendency or regime, has to distort the world and usually does so by drawing off, or separating out, ideas from experience. Ideology, in Orwell’s eyes, could never afford to get too close to the lives of the people. The more abstract the idea and the language that that expressed it, the more ideological the work and vice versa’, he writes at the book’s beginning.

‘[Orwell] knew that if he was saying something so abstract that it could not be understood or falsified, then he was not saying anything that mattered’, Colls continues. ‘He staked his reputation on being true to the world as it was, and his great fear of intellectuals stemmed from what he saw as their propensity for abstraction and deracination – abstraction in their thinking and deracination in their lives. Orwell’s politics, therefore, were no more and no less than intense encounters turned into writings he hoped would be truthful and important. Like Gramsci, he believed that telling the truth was a revolutionary act. But without the encounters he had no politics and without the politics he felt he had nothing to say.’

Orwell was on a collision course with the intelligentsia to which he, as a rebel and a modernist radical, instinctively belonged, but which, due to its embrace of social engineering, the state and Stalinism, he was starting to oppose. His dissidence appears early in The Road to Wigan Pier where, as Colls wisely remarks, ‘Socialism emerges not as the solution but the problem, and the unemployed and exploited emerge not as a problem but the solution’. Colls paraphrases Orwell: ‘The battle of the classes… will not be won in the abstract, or in some future state, but in the present, in how people actually are and what they actually think of each other.’ Orwell despised the ‘Europeanised’ intellectual British Left because they had become wilfully displaced and removed, uprooted from the lived life of their country. Even worse, the deracinated intellectuals, divorced from the majority, wanted to refashion the people in their image. In the world of Beatrice and Sidney Webb and Fabian socialism, gaining political power also meant using the state to engineer the people, through eugenics and public health.

‘The basis of their diet… is white bread and margarine, corned beef, sugared tea and potatoes – an appalling diet’, wrote Orwell in 1936, on the dining habits of the northern unemployed. ‘Would it not be better if they spent more money on wholesome things like oranges and wholemeal bread or if they even, like the writer of the letter to the New Statesman, saved on fuel and ate their carrots raw? Yes, it would, but the point is that no ordinary human being is ever going to do such a thing. The ordinary human being would sooner starve than live on brown bread and raw carrots. And the peculiar evil is this, that the less money you have, the less inclined you feel to spend it on wholesome food. A millionaire may enjoy breakfasting off orange juice and Ryvita biscuits; an unemployed man doesn’t… When you are unemployed, which is to say when you are underfed, harassed, bored, and miserable, you don’t want to eat dull wholesome food. You want something a little bit “tasty”. There is always some cheaply pleasant thing to tempt you.’

Orwell is right, it’s a terrible diet; but liberation from the ‘dreadful destiny’ of the slums does not come through being lectured, hectored or badgered about eating brown bread and raw carrots. For Orwell, life as it is actually lived by people is more important and more real than the whim of ‘every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal wearer, sex maniac, Quaker, Nature Cure quack, pacifist and feminist’ ‘who come flocking’ to the left ‘like bluebottles to a dead cat’. It is better to eat food that is bad for you than to lose the autonomy of choosing something ‘a little bit tasty’. How the unemployed choose to eat, within their narrow means on the dole, is a more important truth about their humanity for Orwell than the dietary exhortations of public-health types ‘who know best’. Those who believe that poor people cannot, or should not, be able to eat what they want do not believe in equality. In fact, the ‘faddish middle classes’, whose outlook is best expressed today by the Guardian, assume that they are superior to the mass of people; hence they feel able to tell them what they should be eating.

It is in Spain that Orwell was to become caught in the middle of a real life-or-death clash between ideology and lived experience. Without Orwell’s book Homage to Catalonia, our understanding of twentieth-century European history would be completely different, certainly if it was based on the accounts then being churned out by the Stalin-loving New Statesman or the fascist Daily Mail. Orwell’s book was born in the May days of 1937, when the POUM and anarchist militias became embroiled in armed clashes on the streets of Barcelona with the hated Civil Guards, as well as the professional and Stalinised Republican army units which were seeking to disarm the militias. While there was typical Stalinist provocation, in terms of the broader rights or wrongs of it all, Orwell’s sympathies were with the republic rather than the POUM. He had rightly seen the limitations of the militias, as they fell well short of the disciplined army needed to fight and win a civil war against Franco’s better trained and commanded fascist troops. So much so, in fact, that Orwell intended to leave the POUM and join the Communist International Brigades. But events overtook him after he returned to the front on 10 May 1937 and was shot by a fascist sniper through the throat.

He left hospital in mid-June just as the Stalinist-dominated republic banned the POUM and issued an indictment against him for ‘high treason and espionage’. Many of his comrades and the POUM’s leadership were in jail, and many would be murdered. To justify the purges, the Stalinist and European-left press began a campaign of falsification and lies to present the POUM as ‘Trotsky-fascists’, traitors and Fifth Columnists who were working for Franco. So estranged from truth was official Marxism and left ideology that the POUM and the anarchists had to be presented as worse than fascists in order to justify their elimination. Orwell took the POUM side though, as Colls notes correctly, ‘not so much [because] he believed the line but because he believed in the men who believed the line’. He might have doubted the twists and turns of the POUM political line, but he could not stomach the lies and stand by while men, like the Italian soldier, were slandered as traitors. ‘The POUM were declared to be no more than a gang of disguised fascists, in the pay of Franco and Hitler, who were pressing a pseudo-revolutionary policy as a way of aiding the fascist cause’, wrote Orwell:

‘This, then, was what they were saying about us: we were Trotskyists, fascists, traitors, murderers, cowards, spies, and so forth. I admit it was not pleasant, especially when one thought of some of the people who were responsible for it. It is not a nice thing to see a Spanish boy of 15 carried down the line on a stretcher, with a dazed white face looking out from among the blankets, and to think of the sleek persons in London and Paris who are writing pamphlets to prove that this boy is a fascist in disguise. One of the most horrible features of war is that all the war-propaganda, all the screaming and lies and hatred, comes invariably from people who are not fighting. The people who wrote pamphlets against us and vilified us in the newspapers all remained safe at home, or at worst in the newspaper offices of Valencia, hundreds of miles from the bullets and the mud. One of the dreariest effects of this war has been to teach me that the left-wing press is every bit as spurious and dishonest as that of the right.’

Orwell returned to Britain in time for the beginning of the Second World War. Apart from taking up the cudgels on behalf of the truth in Spain, without which the historical record would have been badly damaged by the falsifiers, he was not immune to much of the confusion that plagued the left in the run up to hostilities. Should socialists refuse to take sides in a conflict between imperialist powers? Should socialists sabotage the war efforts and oppose rearmament in the face of the threat from Nazi Germany? George Orwell was as confused as anyone else and his writings of 1939 and early 1940 are full of the turmoil and contradictions of the day.

But then in 1940, Orwell took another one of his leaps away from the lines and orthodoxies of leftish ideology which had led many intellectuals into pacifism or the defeatism of toeing the Stalinist line on the Soviet Union’s 1939 pact with the Nazis. In a way, Orwell’s experiences in Wigan and Barcelona prepared the ground. In the Second World War, he would side with the British people, and an imperfect British state, because Britain’s political and wider culture reflected a way of living better than the fascism or Stalinist communism preferred by many of the intelligentsia. He reserved and exercised his right to criticise British imperialism, which he continued to attack throughout the war and his life. Again, his instincts were right or, at the very least, less wrong than most on the left. Instead of abstract ideology, distorted and twisted to suit either a Marxism that was synonymous with Stalinist tyranny, or the elitist social engineering of the Fabians, Orwell advocated a patriotic defence of a way of life that could not be trusted to intellectuals or, by implication, the state.

‘We are a nation of flower-lovers, but also a nation of stamp-collectors, pigeon-fanciers, amateur carpenters, coupon-snippers, darts-players, crossword-puzzle fans’, he wrote in his superb pamphlet, The Lion and Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius, published in 1941. ‘All the culture that is most truly native centres round things which even when they are communal are not official – the pub, the football match, the back garden, the fireside and the “nice cup of tea”. The liberty of the individual is still believed in, almost as in the nineteenth century. But this has nothing to do with economic liberty, the right to exploit others for profit. It is the liberty to have a home of your own, to do what you like in your spare time, to choose your own amusements instead of having them chosen for you from above.’

‘The most hateful of all names in an English ear is Nosey Parker. It is obvious, of course, that even this purely private liberty is a lost cause. Like all other modern people, the English are in process of being numbered, labelled, conscripted, “co-ordinated”. But the pull of their impulses is in the other direction, and the kind of regimentation that can be imposed on them will be modified in consequence. No party rallies, no Youth Movements, no coloured shirts, no Jew-baiting or “spontaneous” demonstrations. No Gestapo either, in all probability.’

As ever, Orwell took the particular character of British people to make a wider, more general point about life versus the ideology of intellectuals and the elite. People don’t need engineering. With some adaptation, his point could equally apply to the French, the ordinary Italian or the vast majority of Germans. It is worth remembering that the extermination of Europe’s Jews did not take place at the hands of popular mobs, but followed the collaboration or ‘realism’ of ruling elites, and was often justified by intellectuals. ‘The power-worship which is the new religion of Europe, and which has infected the English intelligentsia, has never touched the common people. They have never caught up with power politics’, he wrote.

As Colls remarks, Orwell charges the British intelligentsia with being ‘Europeanised’, infected with the cult of power, of the state, marked by their ‘severance from the common culture of the country’. This is not power to reorganise the economy, or to redistribute wealth – all programmes of which Orwell heartily approved – but ‘power over men’, the instinct to remake the people in the image of ideology or the intellectual’s view of the world.

In his greatest novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell creates a dystopia where the identity, the common culture and life of the people is in danger of being obliterated by a totalitarian state that is an amalgam of the Nazi and Stalinist ‘power-worship’ he attacked in the 1930s. The book, as Colls understands well, ‘is not so much a prophecy as a deduction’. It is speculative fiction, where Orwell follows through the logic of a deracinated ideology’s drive to achieve power over man, to socially engineer the soul.

In total contrast to the British popular culture that Orwell sided with, in the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four the state and party are against any private human relationship because it creates bonds that are stronger than ideology, ‘loyalties that it might not be able to control’. To break down bonds, party members (the middle class) are constantly monitored through ‘telescreens’ in their homes, and the state encourages a culture of informing so widespread that ‘it was almost normal for people over 30 to be frightened of their own children’. Winston Smith, the book’s main protagonist and an intellectual, notes sadly: ‘You did not have friends nowadays.’ Later, he mourns that ‘the terrible thing the party had done was to persuade you that mere impulses, mere feelings, were of no account, while at the same time robbing you of all power over the material world’.

The premise of Nineteen Eighty-Four is the near obliteration of what Orwell called ‘the crystal spirit’, in a world where social engineering was refashioning man. One of the book’s great strengths is how Orwell shows that the quest for power over men, and the denial of the space people need to live, drives the state and intellectuals to ignore or suppress facts, even natural laws. ‘The real power, the power we have to fight for night and day, is not power over things but over men’, O’Brien, the sinister party intellectual, tells Smith. ‘Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together in new shapes of your own choosing… Already we are breaking down the habits of thought that have survived from before the Revolution. We have cut the links between child and parent, and between man and man, and man and woman. No one dares trust a wife or a child or a friend any longer. But in the future there will be no wives or friends. Children will be taken from their mothers at birth.’

As well as the nightmare vision of a ‘boot stamping on a human face – for ever’, the cult of power over man leads to a ‘solipsism’ where natural laws can be ignored at the whim of the state. Indeed, by seeking to overthrow life, as it is lived through a common culture of independence and privacy, the state ends up defying physical reality. ‘We control matter because we control the mind. Reality is inside the skull… You must get rid of these nineteenth-century ideas about the laws of nature’, O’Brien tells Smith. ‘Outside man there is nothing.’

Smith is defeated. His doom is predestined because he believes liberation lies in a book written by a party intellectual (modelled on Trotsky) rather than life. At one point, believing O’Brien to be an opponent to the state, Smith swears an absurd and obscene oath to throw sulphuric acid into the face of a child to achieve his ends. Ultimately, Smith is an idiot because he forgets that truth is found in life, not in the ideology of power. The hero of Nineteen Eighty-Four, as Colls understands, is Julia, Smith’s lover. ‘She would not accept it as a law of nature that the individual is always defeated’, muses Smith at the start of their relationship. ‘“We are the dead”, he said. “We’re not dead yet”, said Julia prosaically.’

Julia, like Orwell, understands that life, autonomous, free, even if circumscribed, with self-defining loyalties and bonds between people who value their private relationships, is the highest law. ‘The liberty to have a home of your own, to do what you like in your spare time, to choose your own amusements instead of having them chosen for you from above’, is part of our nature. To try to stamp it out is to stamp on a human face. But even in the tyranny of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Julia not only finds space to live, she makes room for her and Smith to find an intimacy that asserts humanity in a world organised to snuff it out.

Colls gets Orwell, but falters when he tries to fit him into the pigeon holes of left and right, and he badly stumbles when he tries to predict where he would stand on the issues of twenty-first-century British society. Like John Stuart Mill a century before him, Orwell was primarily concerned that ideology was in danger of circumscribing life to the extent that it limited autonomy and damaged people’s capacity to decide for themselves how best to live – the source of human equality. His work is essentially the same project as Mill’s On Liberty, refashioned in the debates over twentieth-century power and politics. The woman in Wigan knew herself that her destiny should not lie in a slum, and that capacity for self-knowledge is what led the Italian soldier, and Orwell himself, to join the POUM militia. Equality is a matter, a law even, of the human spirit – not the abstract measures of a spirit level, as some contemporary social scientists would have it.

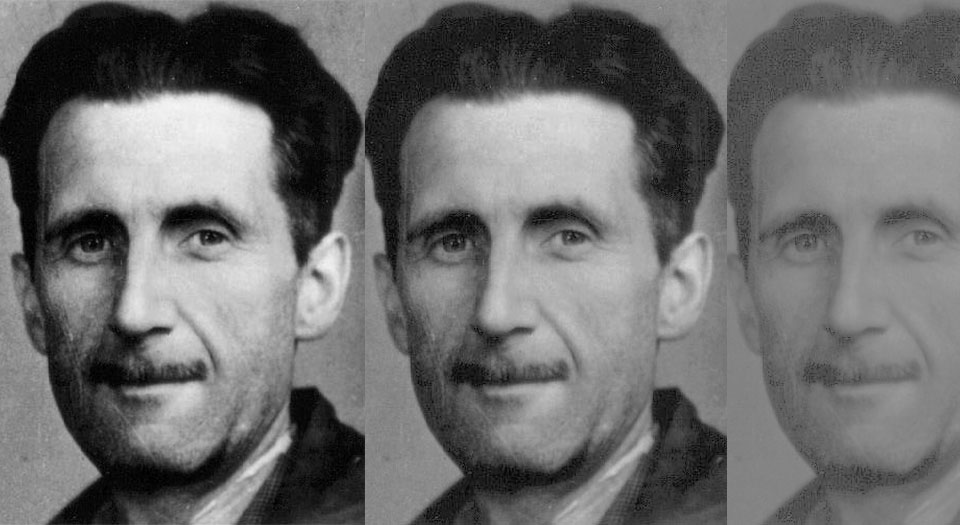

Orwell provides us with a vision of the man he would like to be at the end of his 1939 essay on Charles Dickens, a wonderful piece of literary criticism and something of a personal manifesto. ‘It is the face of a man who is about 40’, writes Orwell of his image of Dickens. ‘He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry – in other words of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.’

Bruno Waterfield is Brussels correspondent for the Daily Telegraph and author of E-Who? Politics Behind Closed Doors, published by the Manifesto Club.

George Orwell: English Rebel, by Robert Colls, is published by Oxford University Press. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.