Why JFK still haunts America

In our cynical, downbeat era, we long for some Kennedy positivity.

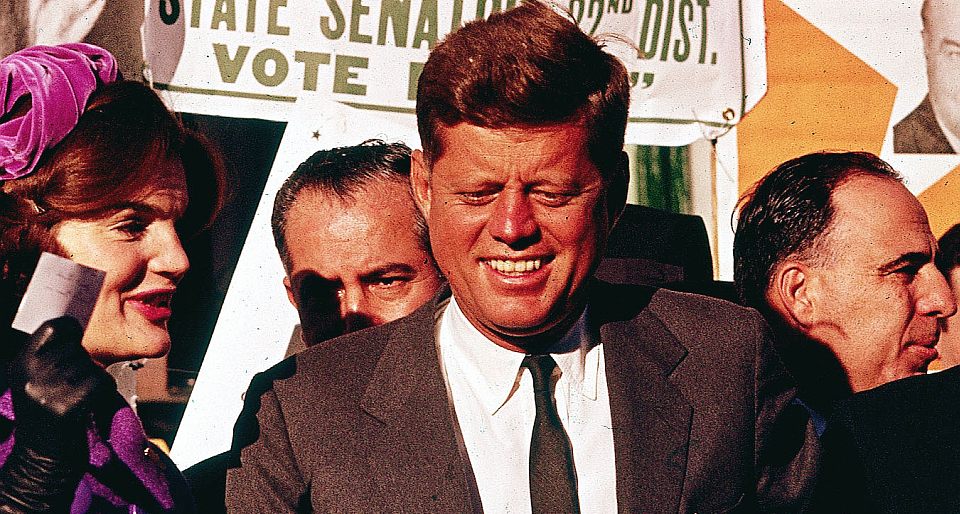

Fascination with John F Kennedy – his life story, his presidency, his death – is something of an American obsession. This Friday, 22 November, marks the fiftieth anniversary of his assassination in Dallas. The images of that day, famously captured on film by Abraham Zapruder, are still able to shock.

To mark the anniversary, America has been flooded with dozens of books, magazine features, movies and TV specials. In one sense, this is nothing new: there has been ongoing interest in JFK, especially concerning the question of who killed him, since that day in 1963. But the character of the discussion about JFK has changed over time.

Kennedy was arguably the first US president who appealed directly to voters on an individual basis, over the heads of the party. The 1960 election was the first one in which television played a major role, and Kennedy was skilful in his use of the new medium. That is perhaps why many people at the time reported that they felt a personal connection with Kennedy. This perceived tie meant that his killing, which itself was a stunning public event, was felt by many to be a personal blow. For years, ‘where were you when JFK was shot?’ was a defining reference among the generation that came of age in the early 1960s.

But as the years go by, the interest in JFK has less to do with shared experience. Today’s stories find it harder to locate eye witnesses to tell how they felt. NBC news anchorman Brian Williams recently told of what it was like for him on the day – but he was four years old at the time.

In the years immediately after the assassination, there was a concerted effort to mythologise the Kennedy years. This began on the weekend following the state funeral in 1963, with Theodore White’s interview with JFK’s widow Jackie, who likened the Kennedy White House to King Arthur’s Camelot. ‘There will be great presidents again, but there will never be another Camelot’, she said. Pro-Kennedy historians such as Arthur Schlesinger wrote favourable books about the man and his record, building on a sense that the era was special, and the man and his record unique.

Fifty years later, you hardly hear about Camelot. Sure, hagiographic accounts continue to be written; for example, Thurston Clarke unpersuasively argues in JFK’s Last Hundred Days, published earlier this year, that JFK was becoming a great president before his life was tragically cut short (to do so, Clarke has to speculate that Kennedy would not have escalated US involvement in Vietnam, and would have successfully introduced civil-rights legislation). But rose-tinted views are much rarer. As a New York Times review of high-school history textbooks found, ‘the portrayal of [JFK] has fallen sharply over the years’: ‘The picture has evolved from a charismatic young president who inspired youths around the world to a deeply flawed one whose oratory outstripped his accomplishments.’

While it is good that uncritical accounts of the JFK years were challenged, some go too far in the other direction, and see Kennedy as nothing more than an empty suit. There is a strain of revisionist US history that views all of the past as a crime, from the mistreatment of native Americans and the slave-holding of the founding fathers up to the present, and Kennedy thus becomes just another step in a long journey of national failure.

Of course, there have always been questions about the events of the day, including whether Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, which have fed Kennedy mania. Conspiracy theories first took off in 1966 with the publication of Rush to Judgment by lawyer Mark Lane, the first notable book to challenge the Warren Commission’s conclusions about Kennedy’s assassination. These were given a fillip by a House of Representatives study in 1978 that claimed (without much evidence) that there was a conspiracy involving two gunmen. Over a thousand books have been written citing a conspiracy, with a variety of organisations accused, including the CIA, the Soviet Union, Cuba and the mafia. Conspiracy theory became prominent in popular culture with the release of Oliver Stone’s JFK in 1991 (highlighting that conspiratorial theories, which at one time were mainly found on the right, had now become mainstream on the left).

What’s notable today is how the discussion of what really happened in Dealey Plaza on 22 November 1963 (the book depository, the grassy knoll, the ‘magic’ bullet, number of gun shots heard, etc) is far less feverish. Yes, many still believe we haven’t been told the full story behind JFK’s assassination. An Associated Press poll earlier this year showed that about 60 per cent of Americans still suspect a conspiracy. And even current secretary of state John Kerry said recently that he has ‘serious doubts’ that Oswald acted alone. But as Marin Cogin writes in the National Journal, the ‘JFK truthers’ peddling alternative theories ‘are regarded as a little bit crazy by the anti-conspiracy writers, the media – and sometimes by each other’. Cogin notes that Stone’s JFK had the unintentional effect of sparking ‘a serious backlash against the conspiracy theorists’. As one complained, ‘they treat us as essentially the same people who believe Elvis lives’. At this stage, it would take some strong new evidence to reinvigorate the ‘who killed JFK?’ debate.

While personal ties, Camelot-mythologising and conspiracy theories are not driving today’s continued interest in JFK, some are trying to use this year’s anniversary to promote their own pet concerns, which have far more to do with current prejudices than events 50 years ago. The new book Dallas 1963, written by Bill Minutaglio and Steven Davis, attempts to pin the blame for the Kennedy assassination on the ‘climate of hatred’ in Dallas, created by right-wing extremists. Of course, this is nonsense, as Oswald was a marginal figure who sympathised with the Soviet Union and Cuba, not a right-wing ideologue. Such arguments clearly try to utilise the past to make points about today’s politics.

Discussing the Dallas 1963 book, George Packer of the New Yorker says the ‘nut country’ of Dallas in the Sixties has ‘migrated from the John Birch bookstores to the halls of Congress’, and while ‘Dallas would like to move on from Dealey Plaza… what’s holding it back is the Republican Party’. This clumsy attempt to link JFK’s assassination with today’s Republicans really doesn’t have much purchase beyond liberal hacks.

With some of the obvious reasons for interest in JFK dropping away over time, why does his story still retain its allure? With the ageing of the population and the removal of JFK’s halo, you might have assumed that the JFK story would no longer captivate, but it does.

Fifty years on, we’re still struck by Kennedy’s youthfulness and glamour, and the contrast with the horrible events of his assassination. It is like he is forever frozen at the age of 46. We tend to think of a certain Kennedy ‘aura’ rather than the specific events in office, like the Cuban Missile crisis. But the fact that youth and glamour still spring to mind when thinking about JFK is not because we’re fascinated with the style of the time (as if we were talking about Mad Men). It’s more a reflection that we continue to recognise that period as one of promise.

The early Sixties were a pivotal period in American history, a time when the US sought to consolidate its postwar hegemony and take the country (and the world) into a new era. Kennedy recognised that America’s purpose needed to be renewed, and he consciously spoke in terms of physical vigour and strength. He himself sought to embody that vigour (even though, we now know, he was suffering from many ailments), and thus did not mind the references to his youthful appearance.

Most of all, Kennedy injected a sense of dynamism and optimism into politics, and people were willing to believe in him. He encouraged public activism and responsibility, in his call ‘ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country’. He aimed high, urging a manned flight to the moon before the end of the decade (even though the technology to do so was hardly evident). Americans were problem-solvers, and there were few limits to what could be achieved – that was his message.

JFK came to symbolise optimism and idealism (even if he didn’t ultimately live up to it), and his assassination appeared to be the death, not just of the man, but of what he symbolised. People hoped Kennedy would bring a new era of prosperity and innovation; but as the years passed, his assassination appeared to mark the beginning of an era of decline. Reagan, Clinton and Obama attempted to reintroduce optimism into American politics, but all paled in comparison with the genuine optimism that greeted JFK, and all ultimately proved to be let-downs.

Today in the US, and elsewhere, we have the opposite of the Kennedy ideal. We stress the need to respect limits (such as environmental limits) and how vulnerable we are (rather than seeing ourselves as resilient problem-solvers). Many are cynical about what can be achieved, especially in relation to politics and politicians.

And yet, the fascination with Kennedy’s demise reflects a semi-conscious desire to recapture a sense when politics could reflect purpose and high aspirations. Until there is a political movement that can convincingly speak with optimism about our human potential, there will be the temptation to look backwards to an earlier time when the possibilities seemed limitless.

Sean Collins is a writer based in New York. Visit his blog, The American Situation.

Picture by: AP/Press Association Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.