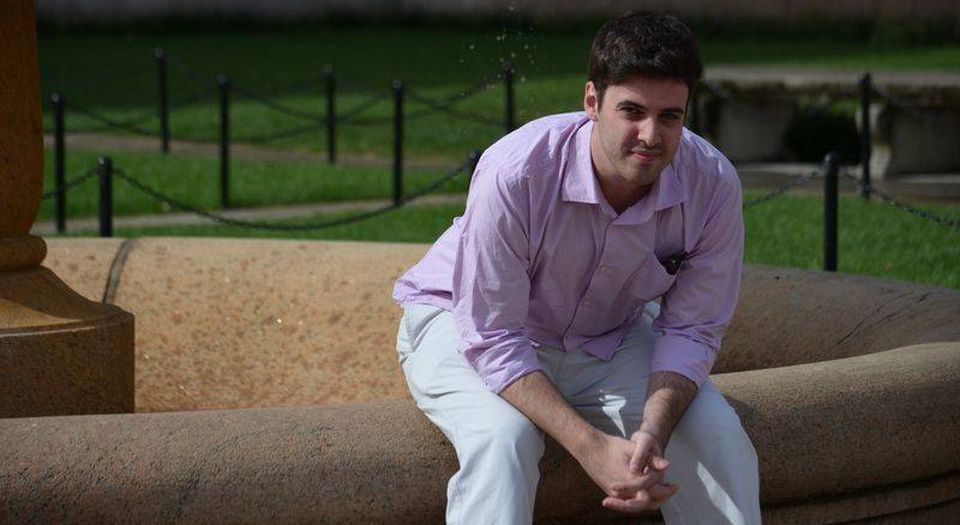

Meet the student who turned his dorm room into an unsafe space

Columbia student Adam Shapiro on why uni should be dangerous.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

A blob is spreading through British universities, devouring once chatty, free-speaking students and pooping them out the other end as self-policing offence-avoiders. It turns every bit of campus it touches into staid zones in which nothing fun ever happens and nothing foul, or even just naughty, is ever said. The blob is called the Safe Space Policy. And as spiked’s Free Speech University Rankings revealed this week, 13 per cent of UK unis now have one. Rolling uncontrollably across campuses, colonising more and more spheres of student life, the Safe Space blob crushes everything from ‘unsafe and unwelcoming’ words to ‘offensive behaviour’, and demands from its quarry that they hold only ‘non-judgemental and non-threatening discussions’ and never tell off-colour jokes, play off-message pop songs, or read off-putting redtop papers. To be Safe Spaced is to be zapped of free thought and turned into a nodding dog of niceness.

But some students are taking a stand against the cult of safeness. Well, in America they are. At Columbia, the Ivy League, super-supposedly-liberal university in NYC, one student rebelled against a request that he, and every other student, hang a sign in their dorm-room windows declaring that their living quarters were ‘safe spaces’ in which ‘homophobia, transphobia, transmisogyny, racism, ableism, classism and so on’ will not be permitted and everyone who enters will be expected to ‘not be oppressive in [their] interactions’. Most students dutifully displayed the Safe Space sign, but one Adam Shapiro, a junior majoring in history, refused. In fact, he hung up a different sign, his own one, declaring his room an unsafe space.

‘People call them safe-space zones, but actually they’re censorship zones, that’s exactly what they are’, Shapiro tells me. ‘Students need to fight back and have dangerous spaces.’ Towards the end of last year, Columbia — home to some of the most PC, word-watching students in the modern West — had at least one ‘dangerous space’: Shapiro’s room. Instead of hanging up the sad ‘safe space’ sign shoved under his and every other students’ dorm door, Shapiro wrote and displayed a sign headlined ‘I do not want this to be a safe space’. His room, the sign said, is a place where all who enter will be expected ‘not to allow identity to trump ideas [or] emotion to trump critical thinking’. ‘Whether you’re black, white, Latino, Asian, Native American, gay, straight, bi, transgender, fully abled, disabled, religious, secular, rich, middle class or poor, I will judge your ideas based on their soundness and coherence, not based on who you are’, his sign declared. Then there was the sign-off, in bold, a warning to anyone who thought they could pop into this student’s room and arrogantly expect that certain things would not be thought, said, or argued out: ‘This is a dangerous space.’

‘I came to university because I wanted to be in a dangerous space in which controversial ideas could be explored’, Shapiro tells me. But safe-space policies, he says, militate against such open-ended, free-wheeling and, yes, sometimes difficult thought-excavation by chilling what can be thought and discussed. ‘The idea behind them seems noble: to be kinder to each other — I’m all for that. But the underlying principle is that there are certain rules that you can’t break and certain things that, if you say, the discussion will be closed.’ Once a safe-space is created, he says, anyone can say to anyone else ‘That’s really offensive, and shut an idea down and not engage with it’. So what is presented as a morally upstanding stab at keeping students safe from harm is in fact more about cushioning them from controversy, from ideas. ‘That isn’t what I came to university for’, Shapiro says.

In many ways, Shapiro’s self-made ‘dangerous space’ sounds a lot like the ideal of the university itself — a space in which, as he put it in his college magazine the Columbia Spectator, ‘we can be relaxed enough to be embarrassed by our ignorance… we can be embarrassed and embarrass each other’. He tells me he often thinks of the words of US philosopher Cornel West, who said education is a process through which you’re ‘unearthed and unsettled’. College should be about ‘giving up old ideas and challenging assumptions’, Shapiro tells me, but ‘this isn’t happening now, because as soon as someone is uncomfortable, the discussion is quickly shut down, whether that’s in a student group, a dorm or a classroom’. Yet despite standing up for the pretty historic and Enlightenment-bolstered notion of the university as a place where one is made precisely uncomfortable — by books, by words, by ideas that call into question what we think we know and think is good — Shapiro received a load of flak for his ‘dangerous space’ sign and the article he wrote about it. Angry students played the privilege card, saying it was typically arrogant of a straight, male, white student — ‘what they presumed to be my identity’, says Shapiro — to say ‘let all ideas be heard’. The safety-worshipping students never stop to think how insulting they are being to ethnic-minority students and other identity groups when they say that free and open debate is too difficult for them and is something only the white and middle class can properly cope with.

Shapiro recognises the danger to coming out in favour of ‘unsafe spaces’ — which is that people will paint you as someone who thinks students should be physically unsafe, forced to negotiate their way through insults and maybe even a bit of argy-bargy. But he makes clear that he’s challenging the nonsense idea of ‘mental safety’. ‘No one should be threatened physically or insulted purposefully’, he says. ‘But anything which explores an idea should be preserved. There’s a difference between calling someone a faggot and saying “I wonder if a family is best raised by a mother and a father?”. I happen to think that position is wrong, but I think it’s a position that should be fully explored in a university. Right now, though, if you were to bring that up in a classroom, you would be eaten alive.’ Of course students, like all citizens, have a right to be free from physical harm. But a right to feel mentally comfortable, and never truly challenged? ‘That isn’t a right’, says Shapiro, and if instituted, it would threaten university life, he says.

Even though, late last year, the Columbia student body were asked to make their personal zones ‘safe spaces’, Shapiro recognises that ‘the goal is not really the dorm — the goal is the classroom’. New PC, intolerant, controversy-allergic student leaders, and some academics, too, ultimately want to make learning zones ‘safe’, by which they mean censored, strangled, bereft of difficulty. Shapiro tells me of his media studies professor who showed his class a film about perspective, about how important the eye of the beholder is in filmmaking, which contained a shot of a father shoving his son. At the follow-up class, the professor had to apologise — for ‘showing the film without a trigger warning’. Shapiro sees trigger warnings, in which students expect to be warned in advance about potentially upsetting class content, and microaggressions, where pretty much any kind of speech can be treated as aggressive to a certain group of people, as standing alongside safe-space policies to form a kind of Holy Trinity of anti-intellectualism, debatephobia, hostility towards difficult ideas. He thinks this infantilisation of students will impact hard on the content of intellectual life in the West. ‘It will be interesting to see the quality of thought that comes out of Columbia, Yale, Harvard, Cambridge and Oxford 20 years from now, because right now people are being infantilised and are not being pushed beyond their limits, to truly think.’

Shapiro says one of the most frustrating things about the response to his creation of a dangerous space — of a small corner of old-style university life on an otherwise safety-colonised, trigger-warned campus — is that some students accused him of defending prejudice and hate. Not so. In fact, as he made clear in his Columbia Spectator piece, he wants freedom of thought and openness to controversy on campus precisely as a means to defeating backward ways of thinking. ‘We need dangerous spaces where bad ideas can die and good ones can flourish’, he wrote. He tells me: ‘When someone says something hateful and heinous and it makes us feel awful, it also actually makes us stronger for having to interact with it and deal with it. And we should deal with it, not hide from it.’

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.