In defence of the dark Seventies

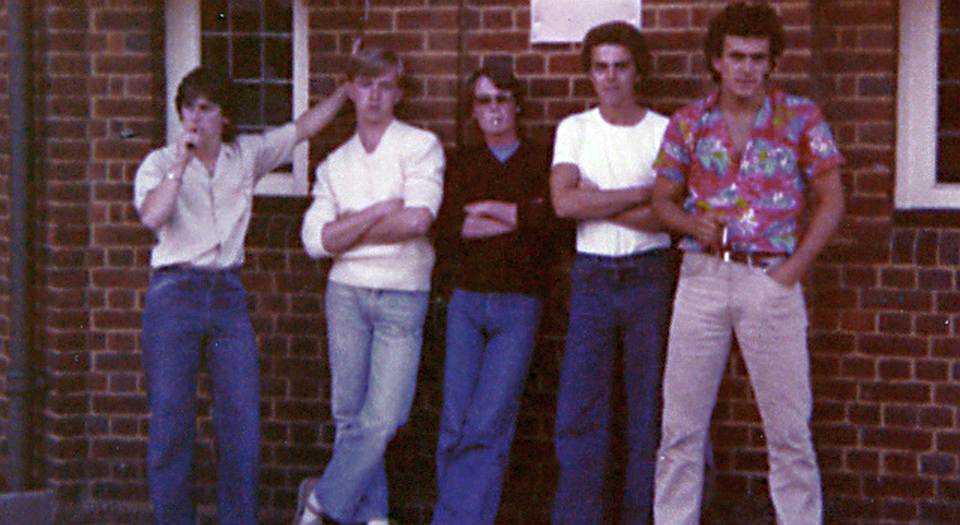

It wasn't all paedos and power cuts says Mick Hume (above, in white jumper).

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Society, it seems, has decided to disown an entire decade of its own recent history – the 1970s. In the UK, we are now supposed to view the Seventies as a dark age of sexual abuse, national crisis and all that, like recovering addicts looking back in bewilderment on our own drug-addled years. When it comes to the Seventies, it seems that the past is not just a different country but another planet, ruled by aliens in beards and flares.

On the other side, the only ‘positive’ things we hear about the Seventies are whimsical celebrations of that decade’s kitsch-kool cultural ephemera, from curly-wurly chocolate bars to chopper bikes.

All of which might say more about society’s disorientation in the present than the sins of the past. It is surely time for another take on the decade that time forgot, or misremembered. In the confessional spirit of today, however, we better start with an admission: I am a Seventies man, shaped by my teenage decade, in a Slade/Sex Pistols, Players Number Six/Watney’s Party Seven, Sta-Press/stack wedges (not to be worn together), You-talking-to-me?/We’re-the-Sweeney-son-and-we-haven’t-had-our-dinner sort of way.

There was certainly much that was grim about the 1970s, to which we would never want to return. But there were things worth defending, too – often the same things that are sneered at today. So, in that spirit, I offer some random observations on the legends of the 1970s. You might think these are guilty of nostalgia, historical amnesia and wild generalisations. I couldn’t possibly comment.

S is for STRIKES. The Seventies, it now seems, was a time of industrial unrest that brought misery to millions, from the power cuts caused by the 1972 miners’ strike, to the 1978-9 ‘winter of discontent’ among public-sector workers that saw streets piled with rubbish and, the headlines cried, ‘the dead left unburied’. Some of that was true; it was no fun finding your home suddenly plunged into darkness on winter evenings, though the three dull TV channels then available were no great loss, and power cuts did provide a novel excuse for the non-appearance of school homework – ‘the miners [rather than the cat] ate it, sir…’

More importantly, however, the mass strikes of the 1970s were about giving millions of people more power, not cutting it off. Collective action in support of better pay and conditions helped to drag many working people out of relative hardship and into the modern age. It wasn’t just the miners striking against the Tories for a £9-a-week pay rise, or the public-sector unions challenging the Labour government’s pay restraints, but also building workers fighting against the casual labour system known as ‘the lump’, and poverty-waged Asian women workers at the Grunwick factory in London striking for two years for the right to organise a union. If there was a problem with the strikes, it was often that trade-union leaders were too timid and entrenched in the system to fight hard enough.

Nor is it true that the strikers were universally unpopular. Apart from the millions involved in the action, many others showed their support and solidarity in spite of the useless union leaders. In popular culture, as Alwyn Turner notes in his history of the 1970s Crisis? What Crisis?, Alan Price had a hit record with ‘The Jarrow Song’ (which advised the unemployed to march on Westminster and ‘burn them down’), while the union-bashing ‘comedy’ film, Carry On at Your Convenience, went down the toilet. Another hit, the Strawbs’ ‘Part of the Union’, was apparently intended as a parody of trade-union power, yet became an unofficial anthem for militant workers. Its lyrics – ‘So though I’m a working man/I can ruin the government’s plan/Though I’m not too hard, the sight of my card/Makes me some kind of superman’ – do indeed seem a world away from today, when real pay is falling and an extended two-hour lunch break passes for industrial action among what remains of the unions.

E is for EDUCATION. The 1970s began with Alice Cooper singing that school was not only ‘out’ but had been ‘blown to pieces’, while a chorus of schoolchildren cheered. It ended with Pink Floyd chanting that ‘We don’t need no education/We don’t need no thought control’, backed by another school choir. Education in the Seventies, it seems, was a dark world of corporal punishment and rote learning before more ‘progressive’ ideas took hold in the classroom.

Well, yes and no. Of course Seventies pupils hated being shut up in school (what right-minded teenager doesn’t?), and the old educational regime could be harsh. But for many bright kids from an ‘ordinary background’, it was the last time they got the chance to experience a proper liberal education, by passing the dreaded 11-plus and going to grammar school. True, we Seventies grammar-school boys did have to put up with the odd stroke of the cane – as the traditionalists say, it never did us any real harm, though it is hard to see how it did us much good, either.

Thanks to the legacy of the grammars, the 1970s were the first decade when no UK prime minister had been to public school; as the grammar schools closed (education secretary Margaret Thatcher shut more than anybody), the 1980s would be the last such decade before the private-school elites took over. Whatever one thinks of selective education, the lowering of expectations for ‘ordinary’ pupils means that the educational gap is larger today than it was 40 years ago, despite the political obsession with ‘social mobility’.

V is for VIOLENCE. ‘Violence, violence/It’s the only thing that will make you see sense’, sang Mott the Hoople in 1973. The Seventies might look like a crazed decade of violent turmoil, from IRA bombings in Britain to US carpet bombings in Vietnam and Cambodia and war in the Middle East. Yet much of the violence of the decade might also be seen as making more sense than today’s conflicts.

In 1974, in the wake of the Birmingham pub bombings that left 21 dead, the Labour government rushed the Prevention of Terrorism Act into law in one day. This draconian act defined terrorism as ‘the use of violence for political ends’. That definition could actually describe the use of force by both governments and opposition movements through much of the Seventies. It was the use of violence for definite and specific political ends. So the IRA bombed Britain in pursuit of Irish unity (though many found it hard to reconcile that political end with blowing up civilian pubs in 1974), the Vietcong fought for national liberation from US imperialism, and Israel and the Arab states fought the Yom Kippur war over clear competing territorial claims. Meanwhile, under the constraints of the Cold War, the great powers refrained from turning every local dispute into a global showdown.

The Seventies was no pacifist picnic. But it does not look quite so mad set against the irrational outbreaks of force and permissive, purposeless interventionism of today. It was the fringe petit-bourgeois terrorist groups of the Seventies such as the Red Brigades, the Baader-Meinhoff gang and the Angry Brigade who more set the tone for the nihilistic terrorism of the twenty-first century – the use of violence effectively as an end in itself. As Francis Wheen observes, the slogan with which the Simbionese Liberation Army ended every communique – ‘Death to the fascist insect that preys upon the life of the people!’ – captured the ‘nihilist hyperbole and exaggerated fury’ of all such Western terrorist groups, whose members were really ‘suffering from little more than existential angst, bourgeois guilt and a nagging discontent at the soullessness and shallowness of consumer society’. Sound familiar?

E is for ENLIGHTENMENT. They might have had some trouble keeping the lights on in the 1970s, but in other ways the ‘dark decade’ looks quite enlightened. Of course, in much of Seventies Britain racism was not so much acceptable as obligatory. But building on the gains of the 1960s, big strides were made in the struggle for female emancipation and gay liberation, and for rights and freedom of expression more widely. It was in this pro-freedom atmosphere that, as Brendan O’Neill has argued on spiked, it would have been weird if a civil-liberties group such as the NCCL had not defended free speech for the odious Paedophile Information Exchange (which is in no way the same thing as defending child-sexual abuse).

The Seventies brought the last set-piece showdowns between the old moral pillars of the British Establishment and the new wave unleashed in the Sixties. The two most notorious of these were the 1971 obscenity trial of the editors of the alternative publication, Oz – which involved the spectacle of the children’s cartoon character, Rupert Bear, standing trial after Oz pictured him having sex with a naked granny – and the 1977 private prosecution for blasphemy brought by Mary Whitehouse against Gay News, over a poem in which a Roman centurion fantasised about having sex with the crucified Jesus Christ. Both trials initially went the way of the prosecution – the Oz editors were jailed, the Gay News editor given a suspended prison sentence – but in the longer run, the public response to the harsh sentences served only further to discredit the old censorious laws.

The irony is that while these battles for freedom of expression were being won, in the student unions the new strand of politically correct No-Platform censorship was growing. Twenty years later, those student union prigs were running the country.

N is for NUTTERS. There was no shortage of Seventies characters who might look like total nutcases today, as Francis Wheen describes in often hilarious detail in his book Strange Days Indeed: the Golden Age of Paranoia. When serious science journalists could suggest the spoon-bending illusionist Uri Geller was actually rewriting the laws of physics, you knew something had become unhinged. But the key factor in the apparent madness of those years was that the British establishment lost its senses – its traditional sense of authority, control and self-confidence.

As society shifted beneath their feet, those at the top saw conspiracies everywhere. Sir Robert Mark, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, said the striking building workers, who were imprisoned for ‘conspiracy to intimidate’ and became known as the Shrewsbury Two, had ‘committed the worst of all crimes, worse even than murder’ and were guilty of ‘the very conduct’ that brought the Nazi Party to power. (One of the jailed men, the now-famous left-wing actor Ricky Tomlinson, later observed that it must have been some ‘conspiracy’, as he had supported the far-right National Front while his fellow prisoner, Des Warren, had been a member of the Workers’ Revolutionary Party.)

Meanwhile, MI5 investigated Labour prime minister Harold Wilson as an alleged Soviet agent, while serious movers in politics and the City of London discussed support for a British military coup. Wheen quotes one gun-hoarding middle-class character from the Seventies sitcom, The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, listing who he is preparing to shoot when ‘the balloon goes up’: ‘Forces of anarchy. Wreckers of law and order. Communists, Maoists, Trotskyists, neo-Trotskyists, crypto-Trotskyists, union leaders, Communist union leaders, atheists, agnostics, long-haired weirdoes, short-haired weirdoes, hooligans, football supporters, rapists, papists, papist rapists…’ and so on and on. It was the British elite that seriously lost it in the 1970s, and its members have never really got it back.

T is for TEENAGE RAMPAGE. If teenagers were invented in the 1950s, and refined and often radicalised in the Sixties, in the Seventies they were often seen as going on a riot rather than a demonstration. Distanced from their parents’ way of life by more than simply years, yet disillusioned by the failures of Sixties radicalism, the teenagers of the Seventies tended to do their own thing, whether as skinheads, punks or football hooligans, in nebulous ‘movements’ that were blown out of proportion by the media, and struck exaggerated fear into the panicky heart of authority.

As the glam rock band Sweet sang in ‘Teenage Rampage’, ‘All over the land/The kids are finally startin’/To get the upper hand/Imagine the sensation/Of teenage occupation/At thirteen they’ll be learnin’/But at fourteen they’ll be burnin…’ All hyperbolic nonsense perhaps, and there was little political about those teen rampages, including punk, which soon fizzled out.

Yet there was something about being a teenager in the 1970s that seems missing now. Sure, we were bored out of our tiny minds, and lacked all the money and fantastic gadgetry enjoyed by the youth of today. But there was also a sense of fuck-you freedom and independence and wanting to leave home for a life of your own, even if it meant living in a hovel. It might be good if we could combine the best of both, and let hi-tech teenagers now embrace and adapt not just the odd song or fashion item from the Seventies, but something of the spirit of the age.

I is for INTERGENERATIONAL RELATIONS. And no, I am not talking about PIE. There was certainly a ‘generation gap’ in the Seventies. But there was also still a culture of contact and interaction between young and older people, that did not involve inappropriate relations.

Before the culture of fear and loathing towards young people completely took hold in UK society, there was a residual sense of adult authority and adult solidarity that proved important in socialising the young. It was not only that neighbours were willing to chastise and give direction to other people’s errant children – something that even parents are often unsure about today. It was also that adults helped young people negotiate the rocky path to some semblance of maturity. One important example of this was the ritual of drinking in pubs. Teenagers would be tolerated in the bar, on the understanding that they learned to drink and behave like grown-ups. Being barred from pubs, and getting smashed and puking in the park, is unlikely to involve any such intergenerational education for life.

E is for the EIGHTIES. Despite all the obvious shortcomings of the Seventies, the defence of that decade would like to enter into evidence the 1980s. I rest my case.

S is for SEX. Contrary to recent reports, in the changing world of the 1970s, there was a lot of sex that involved young people, but not necessarily with dirty old djs, other groping celebrities or predatory paedophiles. As I recall, in those days most people also understood the difference between somebody being a bit of a creep and a sex criminal. Though having spent much of that decade in suburban Surrey, perhaps I am not qualified to comment too much; as our local post-punk heroes the Jam recently recalled, the sexual revolution never really reached Woking.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, There is No Such Thing as a Free Press… And We Need One More Than Ever, is published by Societas. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).) Visit his website here.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.