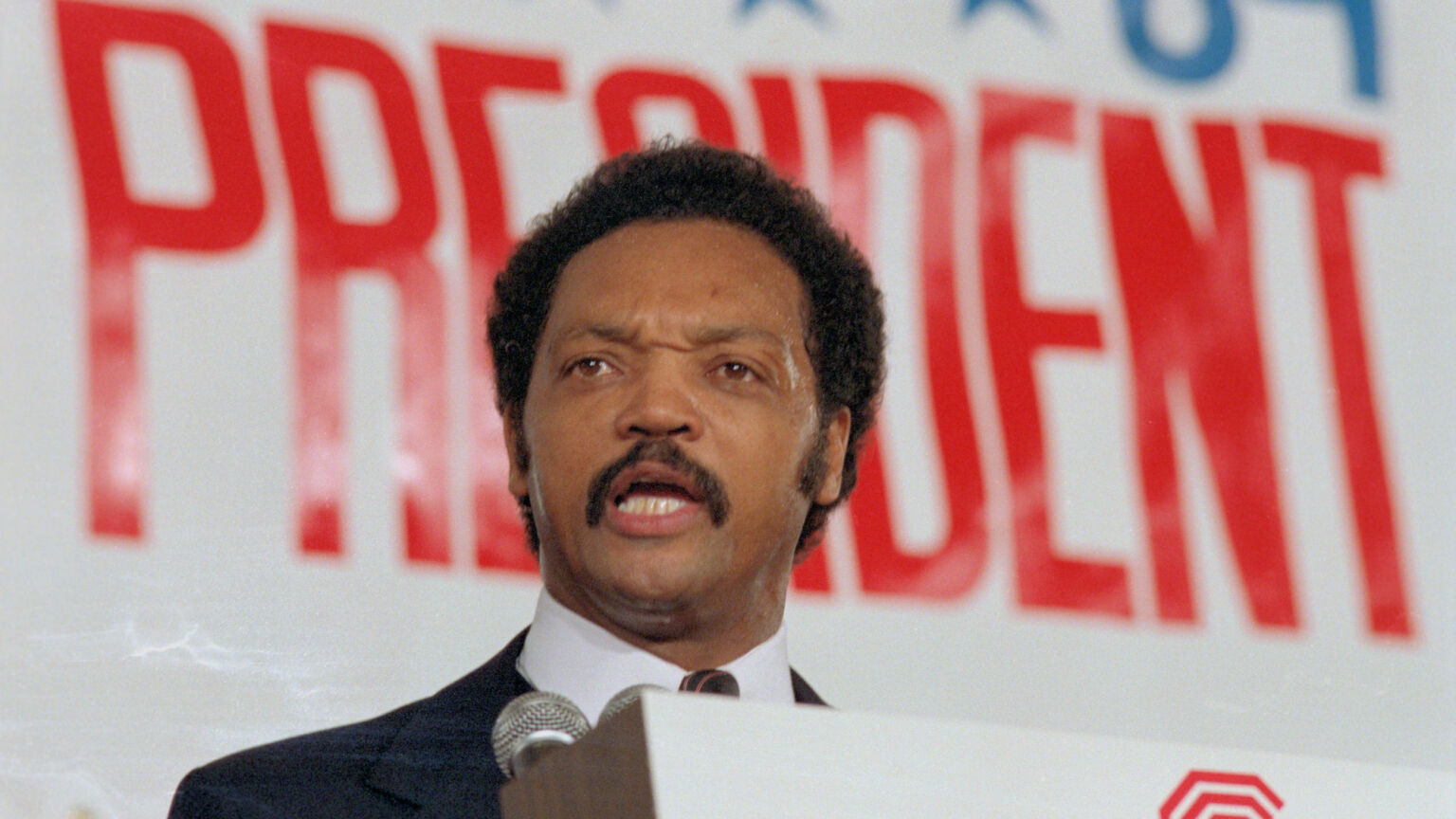

Jesse Jackson: a true political trail-blazer

The one-time civil-rights leader stormed the bastions of American politics.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Reverend Jesse Jackson, who was one of the last living connections with the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, has died at the age of 84. Having been diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy in April 2025, Jackson was admitted to hospital in November last year. He died on Tuesday surrounded by friends and family.

An associate of Martin Luther King Jr and later a Democratic presidential hopeful, Jackson was a hugely important figure. He bridged the gap between civil-rights activism and the subsequent absorption of black civil-rights leaders within local, state and national politics in the 1970s.

Jackson was born Jesse Louis Burns on 8 October 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina. His mother was 16-year-old Helen Burns, and his father a 33-year-old married neighbour of hers. She later married Charles Jackson when Jesse was two. His stepfather was a religious man, and Jackson was brought up in the church – a traditional centre for African-American resistance to repression in the South.

Growing up during the segregation era, Jackson remembered his childhood fondly, stressing the strength of the community. With characteristic eloquence, he recalled his neighbourhood:

‘Mother, grandmother here – teacher over here – and church over here. Within that love triangle, I was protected, got a sense of security and worth. Even mean ole segregation couldn’t break in on me and steal my soul.’

A tall, handsome youth, Jackson did very well at high school. He was elected as class president, excelled in nearly every kind of team sport and was extremely hard-working. One teacher remembered him being ‘almost abnormally conscientious‘. He was loquacious, too, as school-friend Leroy Greggs recalled: ‘He could talk a hole through a billy goat.’

Jackson gained a football scholarship to the University of Illinois in 1959. He claimed his white coaches wouldn’t let him play quarterback, although records show the team already had a black quarterback. This was characteristic of Jackson. Sensitive to any perceived criticism, he often blamed racism for his inability to achieve his goals. Sometimes, it was justified. Other times, it was not.

He left Illinois after a year to attend North Carolina Agriculture and Technical State University, a historically black university. The college at Greensboro, North Carolina, was at the centre of anti-segregation sit-ins, but Jackson was slow to join. He seemed less compelled by the moral necessity of civil rights than by his eventual sense that his leadership was needed. But once he engaged with the protests, he was all in. In 1960, he was arrested with seven other students after a silent demonstration in a whites-only public library, which led to the library being desegregated.

After graduating with a degree in sociology in 1964, he won a scholarship to train as a religious leader at the Chicago Theological Seminary. Having joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which King founded in 1957 to promote a non-violent path to civil rights, his talent was noted by an impressed but slightly sceptical King. Still in his twenties, he was asked to head up Operation Breadbasket, which promoted businesses that hired blacks and boycotted those that did not, first in Chicago and then nationwide.

Jackson’s star rose just as the civil-rights movement began to disintegrate. And in 1968, his life changed. He was with King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, when King was assassinated.

King had held together the SCLC’s quarrelling group of leaders, including Jackson. Some resented the brash newcomer with his eye on leadership. After King died, the resentments surfaced. Jackson aggressively assumed the mantle of leadership, telling reporters that he had cradled King’s head as he died – something disputed by other witnesses. He even appeared on television the day after King’s murder, with his clothes still stained with King’s blood.

Jackson left the SCLC in 1971 to found what was initially called People United to Serve Humanity (PUSH), which campaigned for voting rights, job opportunities, education and healthcare. During the 1972 presidential election, Republican Richard Nixon discussed financing Jackson, as a ‘spoiler’ to divide the Democratic vote. It didn’t work. Instead Jackson went on to campaign for Jimmy Carter by registering those who had never voted before. A huge national figure by 1983, he launched his own unsuccessful bids for the Democratic presidential candidacy in 1984 and 1988, attracting seven million votes during the latter race.

Jackson’s brilliance was attended by flaws. He called the Israeli prime minister a terrorist and, in 1984, referred to New York as ‘Hymietown’, a derogatory reference to its large Jewish population. He also refused to repudiate Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan (even while denouncing Farrakhan’s anti-Semitism).

Like King, his marital infidelities caught up with him. And he was all too quick to attribute both personal and political setbacks to racism – which, as his sympathetic biographer, Marshall Frady, pointed out, was not always the case.

By far the most common charge, however, was that he was an egotist. That he craved the limelight, and was gripped by overwhelming ambition.

Such attacks misunderstand the genius of American politics. Political figures from humble backgrounds – like Abraham Lincoln, Huey Long, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton – required extraordinary self-belief to raise their heads above the crowd. Like them, Jackson was on a perpetual quest for recognition and respect. He was always struggling to ‘be somebody’ – a phrase that, along with ‘keep hope alive’, will forever be associated with Jackson.

Ambition is a key element of political leadership. It takes ambition to transform mediocre men like Franklin D Roosevelt or John F Kennedy into great presidents. The most ambitious American political figure, perhaps, was Lincoln. As his law partner described him: ‘He was always calculating, and always planning ahead. His ambition was a little engine that knew no rest.’ The same could be said for Jackson.

He was socially conservative, the illegitimate child who opposed abortion and prescribed family togetherness for the problems of black America. It was an unpopular message during the socially liberal 1970s and 1980s. But Jackson also encapsulated the liberalism of a bygone age:

‘Liberals liberate – that’s what the word means. Liberation is inherently a liberal process. Moses, Jesus, they were liberals, and Pharaoh, Herod, Pilate, Nero, they were the conservatives. Conservatives want to conserve it all like it is. Liberals liberate and expand what is into what ought to be.’

Jackson was a nearly-man, which must have hurt him. The tears streaming down his cheek at Barack Obama’s inauguration in the famous photograph certainly expressed his joy. But they surely also said something of his disappointment at not becoming America’s first black president himself. He was arguably the man who made Obama’s presidency possible.

There is no question that Jackson helped storm the bastions of American politics, opening it to black Americans. He should be remembered for his political and tactical shrewdness and his eloquence – he once talked young African-Americans out of rioting: ‘If I am somebody, I don’t go out and burn up and tear down. People who are somebody gather up their strength for another fight for the good of the people.’

Jesse Jackson may not have reached the heights he dreamed of, but he blazed a trail for others to follow. His achievements will live on.

Kevin Yuill is emeritus professor of history at the University of Sunderland and CEO of Humanists Against Assisted Suicide.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.