The enduring vitality of Samuel Pepys

Modern outrage at his diaries misses the wit, humanity and insatiable curiosity that make them so compelling.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The recent cancellation of Samuel Pepys by his old school is by no means the first time the diarist’s sexual proclivities have got him into trouble. In the summer of 1663, after bumping into Mrs Lane at Westminster Hall and entertaining her in a local pub with a lobster and some light foreplay, he records similar outrage: ‘Somebody, having seen some of our dalliance, called aloud in the street, “Sir! why do you kiss the gentlewoman so?”, and flung a stone at the window, which vexed me.’

The sex is one of the many joys of the diaries, not least the cod-Spanish and French he uses to try to disguise these moments for posterity. However, it is his insatiable curiosity, rather than his other appetites, that make his diaries so entertaining to read – 360 years after he first stole upstairs to write down his daily jottings.

But according to his former school, the Hinchingbrooke School in Cambridgeshire, Pepys was nothing more than a deviant misogynist. Last week, Hinchingbrooke confirmed it had removed his name from one of its pastoral houses after ‘revelations’ about his ‘treatment of women’ – by which the school no doubt means his occasional violence and notorious philandering. His ‘harmful, abusive and exploitative’ behaviour, the school said in an email to parents, ‘do not align with the values we hold as a school’. It is hard to avoid the suspicion that someone at the school has finally read his work for the first time. His diary has been public for more than 200 years – his behaviour is hardly a ‘revelation’.

Such a narrow view of the great diarist is a tragedy. Indeed, students today could learn much from him. Pepys was writing at the dawn of the Enlightenment and his diaries capture the enterprising spirit of the age. His interests extend to detailed discussions of minting coinage, public dissections, learning geometry and how to use a slide ruler, the latest ship arrived from India or Archangel. He collects the works of Robert Hooke and meets Christopher Wren. He provides commentary on Rubens and some of our earliest critique of Shakespeare. ‘The most insipid, ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life’ was his verdict of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Even to view Pepys as merely an eyewitness to the classic trifecta of the 1660s – Restoration, Fire and Plague – misses the enduring value of his work. Pepys, both a scholar and a rake, loved Londoners as much as he loved London. His vivid portrait of the people and the city, at such a fascinating time in its history, is the work of a humane and curious writer.

‘Lord!’, he begins a passage about a cock fight he has watched in Shoe Lane, ‘to see the strange variety of people, from parliament-man to the poorest ’prentices, bakers, brewers, butchers, draymen and what not; and all these fellows one with another in swearing, cursing and betting’. He also offers advice on how to wear a periwig and on the value of a good turd to start your day (an even more sublime moment incidentally if you happen to have a copy of one of Pepys’s diaries nearby).

Pepys’s story is overwhelmingly a story of London. The energy and happenstance he finds – bumping into people in the street, sharing lifts, meeting in pubs and coffee houses – is still one of the joys of living in such a large city today. It is also striking how familiar Pepys’s London often feels. He buys books in St Paul’s churchyard, haggles over insurance contracts in the City and takes his wife people-watching in Hyde Park.

Arriving on a commuter train to London Bridge today, it is not difficult to imagine what Pepys would have made of London now, with its skyscrapers, low-flying aircraft, tourists and Uber boats. None of it would have escaped his eye – at times humorous, despairing and affectionate. The London our current King Charles perceptively describes as a ‘much-loved and elegant friend’ is the same we find in Pepys’s chronicle.

The behaviour that got Pepys cancelled is undoubtedly beyond the pale today. In an entry from 1664, for example, he recalls hitting his wife, Elizabeth, with ‘such a blow as the poor wretch did cry out and was in yet great pain’. But no man in 17th-century England would meet modern standards of morality.

His contemporary detractors are viewing him through the wrong lens. And so they miss the humanity of his writing. The diaries contain numerous moving passages, particularly those concerning his wife. They become even more poignant when you realise she died at the age of 29, shortly after Pepys gave up chronicling their lives together.

Historians may prefer the recollections of famous kings Charles II, James II or Louis XIV, but the reader today will find Pepys’s record of the tender moments with Elizabeth just as powerful, and probably more interesting. The jokes, worries over money, sulking and fights would feel relevant to plenty of modern marriages. And he often saves the harshest lines for himself. When Pepys develops unbearable, raging jealousy over Elizabeth’s dancing lessons with Mr Pembleton, he writes: ‘God knows that I do not find honesty enough in my own mind but that upon a small temptation I could be false to her, and therefore ought not to expect more justice from her.’

Pepys was enough of an observer of the fallen state of man and an honest critic of his contemporaries to understand that the candid view of life expressed in his diaries would not be to everyone’s taste. Presumably, this was why he also wrote his diary in shorthand. He never intended for his diary to be made public, which is no doubt why it is so fascinating.

But we are lucky it is public. Pepys would be nearly 400 years old if he were alive now, and all those vital characters mentioned in his diaries have long since turned to dust. Yet as a source of inspiration, gossip, social commentary, pathos, and now controversy, they are and remain still very much alive.

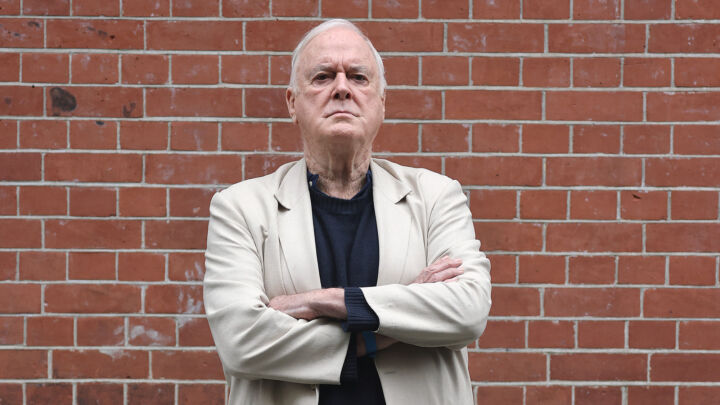

Henry Williams is a writer based in London.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.