When Foucault met the ayatollah

Why the radical postmodernist championed a reactionary Islamist cleric.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

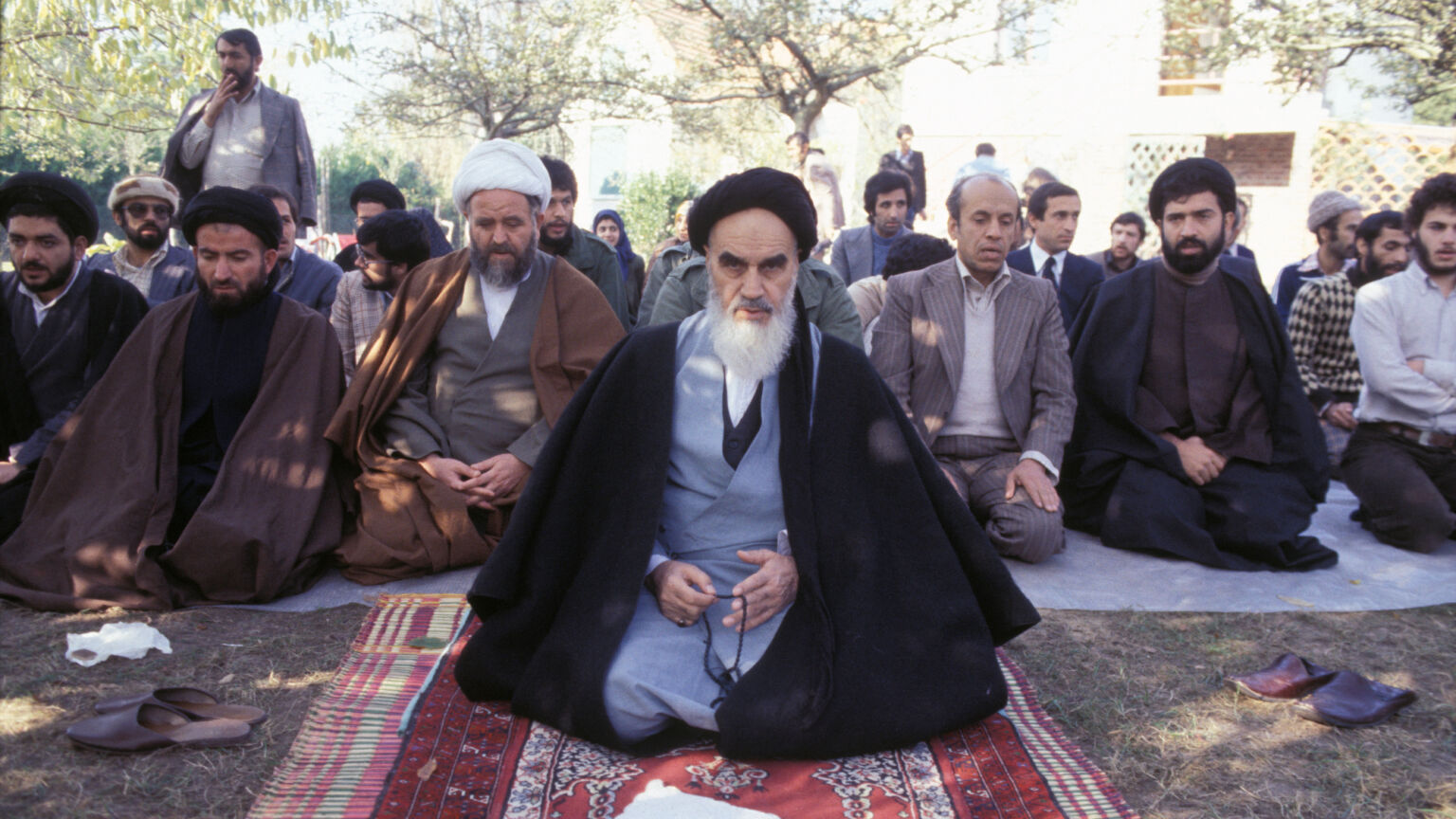

In October 1978, the radical Iranian cleric, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was addressing an audience of Western reporters and intellectuals in Neauphle-le-Château, a village outside Paris. It’s fair to say that most of those present as Khomeini quietly held forth were impressed by this aged opponent of Iran’s sclerotic, corrupt monarchy. But perhaps none more so than one particular French intellectual. He would call Khomeini ‘the old saint in exile’, and praise him as a ‘man who stands up bare-handed and is acclaimed by a people’.

Khomeini’s champion-in-chief was none other than Michel Foucault. Then 52 years old, Foucault was no political naif. He was at the peak of his intellectual powers. He had just published his seminal Discipline and Punish (1975) and his History of Sexuality: Volume One (1976), and was busy writing volumes two and three – works that would go on to cement his reputation as one of the most influential radical thinkers of our time (at least, on university campuses).

This darling of the post-class New Left, this radical critic of modernity, lavished praise on Khomeini – a man who was soon to establish one of the most repressive, brutal regimes on Earth.

Earlier that year, Foucault had been commissioned by Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera to write a regular ‘Michel Foucault Investigates’ column – and other pieces for several French papers, too. The original focus was supposed to be America under its new president, Jimmy Carter. But as the Iranian people began rising up against the shah’s autocratic reign, Foucault’s focus shifted eastwards. And so, between the summer of 1978 and early 1979, he visited Iran twice, and contributed a series of op-eds, features and interviews on what, come early 1979, would culminate in the Iranian Revolution and the birth of the Islamic Republic.

By the time Foucault sat in awe before Iran’s future supreme leader, under the shade of an old apple tree, he had already become a full-throated supporter of the revolt against the shah. Plenty of leftists in the West had. But Foucault’s stance was different. Unlike those Western left-wingers at the time, who supported the revolt in spite of its religious character, Foucault supported it precisely because of its religious character.

At first glance, this may look like a very odd coupling – the Western radical, libertine and poststructuralist, and the Islamist reactionary. But dig a little deeper, and it’s an alliance built on a shared, anti-Western animus. Foucault’s radicalism, drawing deep on a counter-Enlightenment tradition of thought, rested on a profound critique and rejection of modernity as a whole. He conceived of Western society along the lines of Max Weber’s ‘iron cage of rationality’, a spiritless, disenchanted system of domination in which ‘individuals’ are little more than the effects of power. And in Islamism, Foucault effectively saw a solution – a spiritual alternative to the supposedly empty, prison-like rationalism and materialism of the modern West. Indeed, an interview with Foucault published in March 1979 is even called, ‘Iran: the spirit of a spiritless world’.

His embrace of Islamism is clear from a 1978 piece in Nouvel Observateur. There, he talks up ‘Islam[ic] values’: that ‘no one can be deprived of the fruits of his labour’, that liberties will ‘be respected to the extent that their exercise will not harm others’, and that ‘minorities will be protected and free to live as they please on the condition that they do not injure the majority’. But, recognising how close that all sounds to various Western political ideologies, he then criticises the blandness of ‘these formulas from everywhere and nowhere’.

It’s the Islamist character of revolt that lights Foucault’s fire, not the supposed socialism or liberalism of ‘Islamic values’ – something observers of today’s kleptocratic, illiberal Iran would struggle to spot. He claims that it’s the dream of an ‘Islamic society’ that is in ‘the hearts’ of the shah’s opponents. He praises the revolt against the shah as a movement that aims to give ‘a permanent role in political life to the traditional structures of Islamic society’. And he celebrates it for introducing ‘a spiritual dimension into political life, in order that [political life] would not be, as always, the obstacle to spirituality, but rather its receptacle, its opportunity, and its ferment’.

Here, Foucault was drawing on the work of French-trained sociologist Ali Shariati, the so-called intellectual father of the Iranian Revolution, who died in 1977. In his later works, Shariati called for Iranians to throw off the veil of Western modernity, imposed by the shah, and rediscover their authentic cultural selves, their Shia Islamic essence.

Similarly, in a piece written in February 1979 (after the fall of the shah, but before the March referendum that ushered in the Islamic Republic), Foucault talked up the ‘singularity’ of the Iranian revolution, praising it for bringing into being ‘an entire way of life’, reviving ‘a history and a civilisation’. And in the ‘singularity’ of this Islamist revolt, creating a radical alternative to the materialism and rationalism of the West, Foucault identified an immense spiritual ‘force’, a ‘power of expansion’ that could mobilise ‘hundreds of millions of men’.

Foucault was enthusiastically predicting the emergence of Islamism as a transnational force. A movement drawing on pre-modern Islamic histories and cultures, which, as he saw it, would establish a genuinely radical alternative to Western modernity. The growth and emergence of countless, often violent Islamist movements in the Middle East and beyond lends Foucault’s writing a dark prescience.

But that was February 1979. At that point, Foucault could still believe in his own visions of the Iranian Revolution. He could still imagine the Islamic society as a ‘utopia’, as he called it in 1978. By March, Foucault had to reckon with the harsh reality. Within days of Khomeini and his supporters taking control, all women had been ordered to veil themselves and left-wing dissenters were slowly but surely being silenced. On 8 March 1979, protesters came out on to the streets, chanting against the mandatory veils, and ‘Down with the dictatorship’. Pro-Khomeini forces answered the protests with knives and bullets.

Within weeks, and amid a lot of domestic criticism, Foucault had stepped back from his support for Khomeini’s vicious Islamist movement. The brutally repressive reality of its ‘semi-archaic fascism’, as one of Foucault’s critics called it at the time, had shaken him awake. He wrote a desperate letter to the then Iranian prime minister, registering his anger, and then retreated, shame-faced, from the fray.

By embracing radical Islamist reaction, Foucault succumbed to the temptation that still confronts today’s decadent bourgeois anti-modernists. He at least realised his mistake very quickly. Today’s ‘progressives’ should take note.

Tim Black is associate editor of spiked.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.