Long-read

The trouble with the Nuremberg Trials, 80 years on

They exposed the unparalleled crimes of the Nazis – but also reduced them to products of individual psychopathy.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Eighty years ago, at 10 o’clock on 20 November 1945, the courtroom in the Palace of Justice, Nuremberg, Germany, was crowded. Present were lawyers, generals, soldiers, white-helmeted US military police, photographers, movie cameras, journalists and locals. Punctually, the four judges began the proceedings of the International Military Tribunal.

It was ‘International’ because of the four Allies – America, the Soviet Union, Britain and France. And it was ‘Military’ because they were occupying powers. There was no German government.

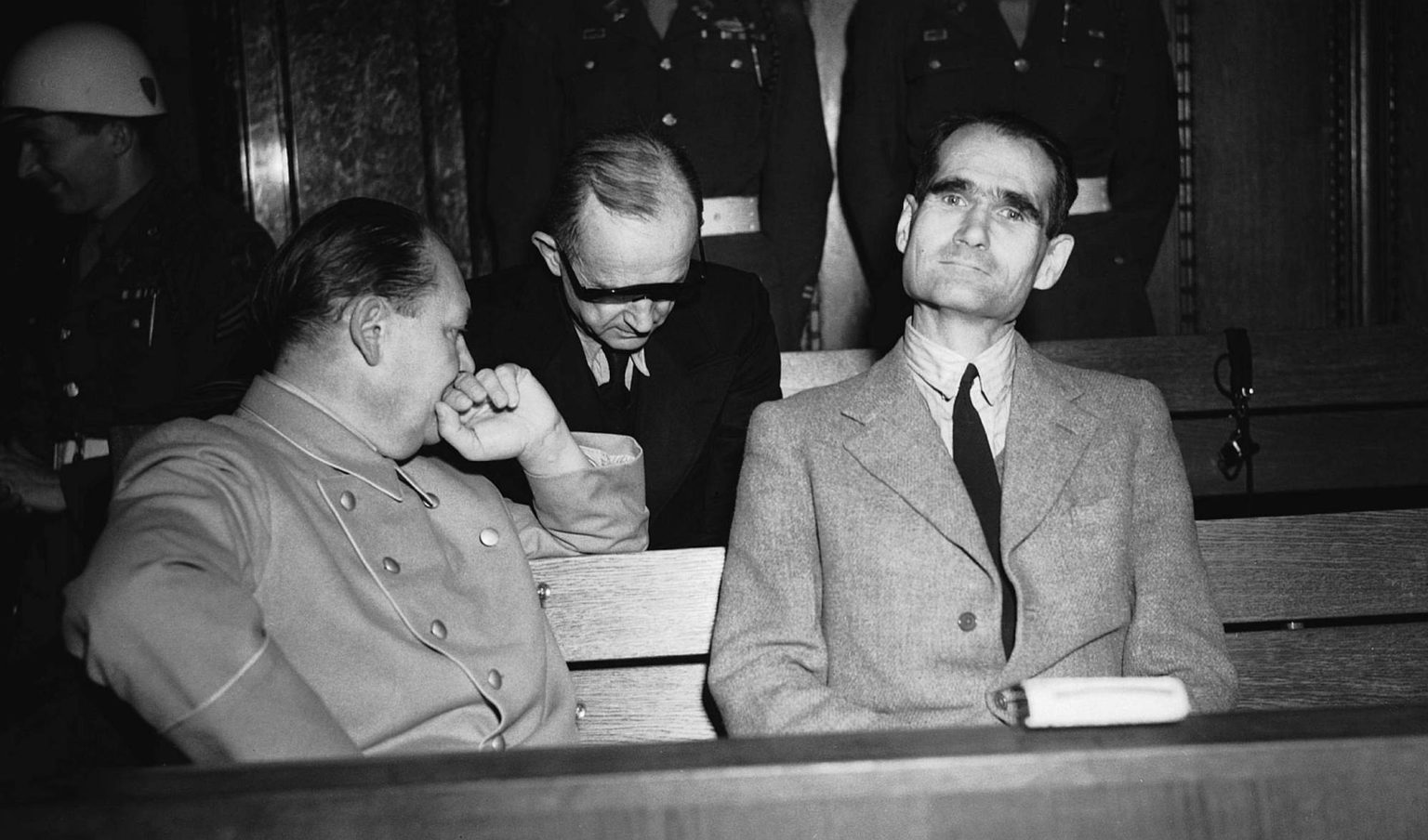

A procession of more than 20 top Nazi officials, led by former Luftwaffe chief Herman Goering, came up from dank, windowless solitary confinement elsewhere in the building, and took to two rows of serried seats. The lights in the panelled room were almost as intense as those shone by each black-helmeted GI as he inspected his own personal captive – known by just a number – in the cells.

And so began what soon became known as the Nuremberg Trials. There’s plenty of largely black-and-white footage and photography of the trials. They show the indicted Nazi leaders wearing headphones, enabling them to hear the proceedings by means of a then novel system: simultaneous interpretation. Goering and one or two others are shown in uniform; the rest, in suits and ties. Sometimes, perhaps because of the bright lights, Goering, Admiral Doenitz and the odd accomplice would don dark glasses which, compounded by headphones, make them look spookier than ever. Throughout, Goering was contemptuous. Albert Speer maintained a calm bearing. Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s party deputy, looked madder and madder.

Nuremberg was more than a courtroom drama. For more than 10 months, the Allies not only ensured that some kind of justice was done there. They also contained the populist and radical worldwide atmosphere of anti-fascism immediately after the war, by making justice seen to be done.

They had alighted on Nuremberg as the venue for the trials, because it was the historic seat, with Munich, of Nazism. Nuremberg had been where the architect and wartime Nazi arms chief Albert Speer had organised Hitler’s famously full-on annual party rallies. It was also where Hitler’s deputy, Rudolf Hess, first promulgated the 1935 Nuremberg Laws. These deprived Jews of the right to intermarry and have sex with Gentiles, stripped them of citizenship and, beyond the Jews, threatened ‘even those who silently distanced themselves’ from the Nazis by their ‘lack of enthusiasm’ with the same lowly status.

In Nuremberg, the Allies hoped that a sober judicial ritual would act as a cool riposte to the hysteria that had always surrounded Hitler in this particular city. The trials were a huge gamble, but, by and large, the Allies pulled it off. They were succeeded by 12 separate trials, from December 1946 to April 1949. These subsequent hearings covered Nazi generals, doctors and judges, as well as ministerial officials and major companies (IG Farben, Krupp) associated with the Nazi regime.

The legacy of the Nuremberg Trials hangs heavy over the past eight decades. One reason is that in Nuremberg we have a template for postwar declarations, principles and conventions that came to define much of today’s international law on war. Though times have changed since 1945-6, and the Nuremberg legal approach has been widely and seriously distorted, contemporary international institutions and tribunals on war crimes often still invoke Nuremberg to claim legitimacy.

Indeed, in all respects, the times have changed beyond recognition. The distance is vast between then and now. In 2025, it remains important to realise just what those in the dock in 1945, who had outlived the suicides of Hitler, Himmler and Goebbels, had done. It is important because the term ‘fascist’ is used so liberally today to refer to anyone from Donald Trump to Nigel Farage. This completely relativises what happened in the 1930s and 1940s, and obscures the horrific dimensions of the Holocaust.

And the Nazis’ deeds, captured to some degree at the trials, were horrific. At a later Nuremberg trial, Otto Ohlendorf, appointed by SS chief Reinhard Heydrich as commander of the death squads (Einsatzgruppen) in the Ukraine and Crimea, described one feature of Nazi rule. To save money and the feelings of his executioners, the SS developed lorries with airtight space behind their cabs. They were mobile gas chambers, using the exhaust fumes lorries produce to deadly effect. The lorries ‘looked very harmless, so there was no panic when the victims were loaded… there was no excessive stress for the truck driver or his mate, as the engine noise drowned the cries of the dying’. The lorries were equipped with a ‘rapid discharge device’, or tipping mechanism, so as to more swiftly unload bodies into freshly dug pits.

In October 1941, one engineer noted that no fewer than 97,000 victims were ‘processed’ in just three vehicles, ‘without any faults appearing’. At that time, victims were crammed into lorries at the rate of nine or 10 per square metre. By 5 June 1942, however, the same engineer looked forward to squeezing still more Jews and communists into the same space (1). In Mogilev, Belarus, gassing by lorries took place after midnight, for cover, and lasted just 10 minutes; after it was over, Jewish prisoners would clean the lorry’s space of vomit and faeces, before themselves being shot (2).

At Nuremberg, the defendants were charged on four counts: Nazi common plan or conspiracy; crimes against peace (waging aggressive wars and / or wars that broke treaties); war crimes (killing of prisoners of war etc); and crimes against humanity. The latter category included concentration camps and other mass exterminations, medical experiments (children included), deportations for slave labour.

The last count, the rather blurry ‘crimes against humanity’, had not been defined at all before Nuremberg. It drew attention to the exceptional horror of the Holocaust. But it also tended to strip the Nazis’ methods of their historical and political context.

But that was just the point. It was not so much fascist politics that were put on trial, but, ironically, humanity itself. As Ann and John Tusa’s old but much-acclaimed account, The Nuremberg Trial (1983), has it, ‘It was part of the search for a better way to control strong human impulses, aggression and revenge. It was an attempt to replace violence with acceptable and effective rules for human behaviour.’

At the same time, the left-liberal writer Rebecca West, observing parts of the trial toward its end, opined that its task was ‘to prove that victors can so rise above the ordinary limitations of human nature as to be able to try fairly the foes they vanquished, by submitting themselves to the restraints of law’ (3).

Nuremberg, then, amounted to a juridical attack on evil. To its credit, the tribunal recognised the extraordinarily monstrous deeds of the Nazis. To its discredit, and despite its key charge of conspiracy, it tended to convert the historical experience of fascism into a timeless morality play – indeed, Robert Jackson, the chief US prosecutor, invoked ‘the moral sense of mankind’ in his opening address. The impulse was to portray the Nazi leaders as criminals able to dupe a pliant German population. The focus was on individual sinners, their psychology and their blind group loyalty to Hitler.

It could be argued that the focus of Nuremberg on Nazi evil excused the crimes of the Allies, from the blanket bombing of Dresden to the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nevertheless, it should be clear that the size, ferocity and duration of Nazi exterminations was of a different nature to the actions of the Allies. And the Nazi barbarism completely dwarfed anything that might be cast as fascism today. To even suggest that Donald Trump’s presidency is akin to the Nazis’ reign of horror is moral ignorance.

The origins of the Nuremberg Trials are knotty. In the run-up, there was much indecision about what to do with the defendants. Three months after the success of D-Day, Roosevelt joined Churchill in initialling a programme drawn up by US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau. This sought simply to identify Nazi ‘arch-criminals’ whose guilt was ‘obvious’, and ‘put them to death forthwith by firing squads made up of soldiers of the United Nations’.

But by the time of the Yalta ‘Big Three’ conference in February 1945, Stalin came out in favour of a trial – before, that is, the dispatch of defendants, again by firing squad. The founding of the United Nations at the San Francisco Conference in April 1945 confirmed America’s hegemony in the world and its revised plans to go to trial, which Britain had no choice but reluctantly to accept.

There was a wider political context to the push for a tribunal. The Allies were keen to play to and contain mass anti-fascist sentiment. A great fear, after D-Day, was that Allied soldiers and others would visit revenge on the remnants of fascism, and so create disorder. Nuremberg took the sting out of populist anti-fascism. It took the whole nine yards of fascism, reduced them to man’s inhumanity to man, and depoliticised them.

This was not just a victory for lawyers over politics. It was also where the character analysis beloved of the burgeoning wartime discipline, psychology, came into its own. Thus prosecutor Jackson reminded Hjalmar Schacht, appointed by Hitler as Reichsminister of economics in 1934, of the opinion about Goering that he had shared with British intelligence interrogator Major Edmund Tilley. According to Schacht, Goering was:

‘Endowed by nature with a certain geniality which he managed to exploit for his own popularity, he was the most egocentric being imaginable. The assumption of political power was for him only a means to personal enrichment and personal good living. The success of others filled him with envy. His greed knew no bounds. His predilection for jewels, gold and finery, et cetera, was unimaginable. He knew no comradeship. Only as long as someone was useful to him did he profess friendship.’

This was an early and influential form of the personalisation of politics. It rests on the assumption that politics can be reduced to and explained away by an individual’s putative psychopathology. So it is notable that both Schacht, a placeman for the Nazis, and Jackson took this psychological explanation of Goering as good coin.

That was not by chance. Lieutenant colonel Douglas Kelley, a US Army military intelligence officer who served as chief psychiatrist at Nuremberg, claimed to have spent no fewer than 80 hours with each of the prisoners he assessed. US Army first lieutenant Gustav Gilbert, a Jew with flawless German, was also appointed psychologist to the prisoners.

Before and during the trial, the two men played soft-cop listeners to the defendants in their confinement, with Gilbert using the results to help guide Jackson with his case. Like Jackson in court, Gilbert coached Speer in his cell. That way Speer’s acceptance, at the trial, of personal and collective responsibility for fascist misdeeds could undo Goering’s combative oratory for and leadership of those in the dock, and work to the Allies’ maximum advantage.

Interestingly, Kelley and Gilbert also administered the newly trendy Rorschach inkblot test to the defendants. ‘Psychiatry and psychology’, in the words of one Californian academic,

‘were oddly central to the trial in ways that are largely forgotten. First of all, the trial was not so much “who done it” as it was a “why did they do it”… This was an enormous and unusual effort in the history of medicine. Never before, have we studied so closely leaders who had steered a country into such an abyss.’

Indeed, never before had inkblot marks on a piece of paper been used to provide an explanation of barbarism.

The rise of psychology during the war had, back in June 1945, allowed American professional associations dedicated to mental deficiency, neurology, psychiatry and unrelated disciplines to write a letter to Jackson saying that ‘detailed knowledge of the personality of these leaders… would be valuable as a guide to those concerned with the reorganisation and re-education of Germany’. Significantly, General William J Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (forerunner of the CIA), backed the letter – and the Rorschach tests.

Then the shrinks got another break. At the trial, Rudolf Hess appeared increasingly dotty. If he was deemed unfit to stand trial, Nuremberg itself would come into question. So when, under pressure from the psychologists, Hess owned up to faking it, it boosted the legitimacy of the trials and the shrinks’ methods. Once again, and despite the charge of conspiracy, the politics of Nazi rule were reduced to egocentrism and other personality disorders.

The legacy of the Nuremberg Trials is all about us today. It is still lauded as an eternal model for how the ‘global community’ should deal with national dictators. It was preceded by the UN’s hope that ‘respect for international law’ could ‘save succeeding generations from the scourge of war’. And it was succeeded, in 1950, by the UN’s seven Nuremberg Principles, which hold both heads of state and juniors ‘following orders’ to account for their deeds in wars. Yet the overall and time-bound social legitimacy of the trial should warn us against attempts, made 80 years later, to repeat it. Conditions now are very different from Nuremberg: any international court on wars can rely on much less cohesion or popular support.

More broadly, the Nuremberg Trials have played a key role in dehistoricising and psychologising the historical phenomenon of fascism. They have helped fuel, in recent years, the constant anti-populist refrain of today’s establishment – namely, that in Donald Trump’s election victories and the populist revolt throughout Europe we are witnessing the rise of fascism again. That the psychopathology of fascism is alive and well in the shape of MAGA and Reform UK. Indeed, ahead of this month’s release of Nuremberg, a new film about the trials, one of its stars, Remi Malek, who plays the shrink, Douglas Kelley, drew a clear parallel between Trump’s rise and the rise of the Nazis.

There we have it. Instead of political analysis of fascism, we get glib analogies. Instead of understanding what fascism was, we get swipes at the perennial gullibility of the masses. Instead of a true reckoning with the evils of the Nazism, we get anti-populist, anti-democratic prejudice dressed up as anti-fascism. This is the dubious legacy of the Nuremberg moment.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University. He tweets at @jameswoudhuysen.

This is an edited version of an essay that first appeared in November 2020.

(1) Data and quotations from Justice, not Vengeance [1989], by Simon Wiesenthal, Mandarin, 1990, pp71-2

(2) Hitler’s Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder, by Helmut Langerbein, Texas A&M University Press, 2003, pp115-116

(3) Both quotations from The Nuremberg Trial, by Ann Tusa and John Tusa (1983), Papermac, 1984, p14

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.