Long-read

The book-burners have taken over the publishing house

Sensitivity readers and ultra-woke staff are censoring works that deviate from 'progressive' dogma.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

In the mid-2010s, people began to notice something strange happening on college campuses. In the past, wealthy donors tried to censor professors and students. But then the demands started coming from the students themselves. More interestingly, the demands were being expressed in the language of public safety. It was ‘dangerous’ for Bret Weinstein, a professor who criticised the tactics of an anti-racist protest, to teach at Evergreen State College. It was ‘harmful’ for Erika Christakis, a professor who questioned the wisdom of banning certain types of Halloween costumes, to retain her position at Yale University. It was ‘violence’ for Charles Murray, author of The Bell Curve, to give a talk at Middlebury College. The Great Awokening, as it would later come to be called, had transformed America’s colleges.

Something similar has been happening inside America’s publishers. One vice-president at a Big Five publisher, who did not want to be identified in this piece, told me that there have been ‘more changes in the past five years than the previous 20 to 25’. The changes have been fuelled by the rise of Bookstagram, BookTok and Twitterature (a portmanteau of Twitter and literature) – and, of course, by the Great Awokening. Today, anyone with an internet connection can accuse a book of racism, sexism or transphobia. Across the board, American publishers have reshaped their editing policies in response to social-media outrage.

Sensitivity readers, individuals who are hired to eradicate potentially offensive material from books, were largely unknown until 2016, the same year young adult (YA) author Justina Ireland built a database of sensitivity readers. Uncoincidentally, this was the same year Donald Trump was elected to the Oval Office. In less than a decade, sensitivity readers have become a routine part of the editing process. Whether it’s picture books or adult novels, and even the pages of Science magazine, the most extreme people on the ‘progressive’ left now have an important, and frankly unprecedented, role inside American publishers. Indeed, Ireland and other sensitivity readers’ attacks actually fuel the demand for their services.

‘We’re now using sensitivity readers a great deal’, one president at a Big Five publisher explained to me:

‘The sensitivity readers that we’re employing are at the very, very, very farthest edges of the cultural police. They are over vigilant to a large degree. It’s great to have the most extreme possible reaction to a book, which catches even the most apparently neutral points and casts a severe light on them.’

As a vice-president at a different major publisher put it to me:

‘We are very interested in trying to suss out what books might cause a problem on social media, which can come back in our faces in terms of sales. Nobody wants to publish a book that social media is going to cancel. It’s unpleasant, it can be hurtful, it’s upsetting and it’s not good for business.’

While publishers are focussed on their bottom line, many literary agents are more focussed on protecting their authors from edits. If you can imagine a National Book Award winner edited against their will by a 22-year-old sensitivity reader, who just graduated from a gender-studies programme at Yale, then you can imagine the frustration of the agents I talked to, many of whom have been selling books to the Big Five for decades.

As one literary agent told me:

‘Someone will say, “Oh, I’m a little concerned about this. This character’s misogynist.” And I say, “He’s misogynist. They exist. They existed at the time. They exist now.” It was set in 1920. That’s how they spoke. We’re not going to give them the vocabulary of 2022. It’s just not going to happen, and it shouldn’t happen.’

Another agent, who represents a veritable who’s who of contemporary authors as well as the estates of many deceased canonical authors, put it this way: ‘You can’t say Cormac McCarthy is a butcher because his main character is a murderer.’ But today, you really can. And the biggest publishers in the world will listen. As one Pulitzer Prize finalist lamented, ‘This is the silly season’.

To be sure, not everyone inside the Big Five publishers is on board with what I have called the ‘sensitivity era’ in American publishing. One vice-president, in our interview, spoke plainly when pondering those who want to restrict the kinds of characters who can be included in fiction: ‘it’s a fucking novel.’

Yet this same vice-president would not let me record our interview. While one might expect genuflection from interns faxing memos, brewing coffee and struggling to keep up with New York City rent, it is a sign of the times that even the rich and powerful are afraid to say what they think.

Indeed, the most frequent admission I heard while conducting interviews for my new book – That Book Is Dangerous! How Moral Panic, Social Media and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing – was ‘I wouldn’t have done this interview if it wasn’t anonymous’. If you had heard the fear in these people’s voices, you would think we were discussing official secrets.

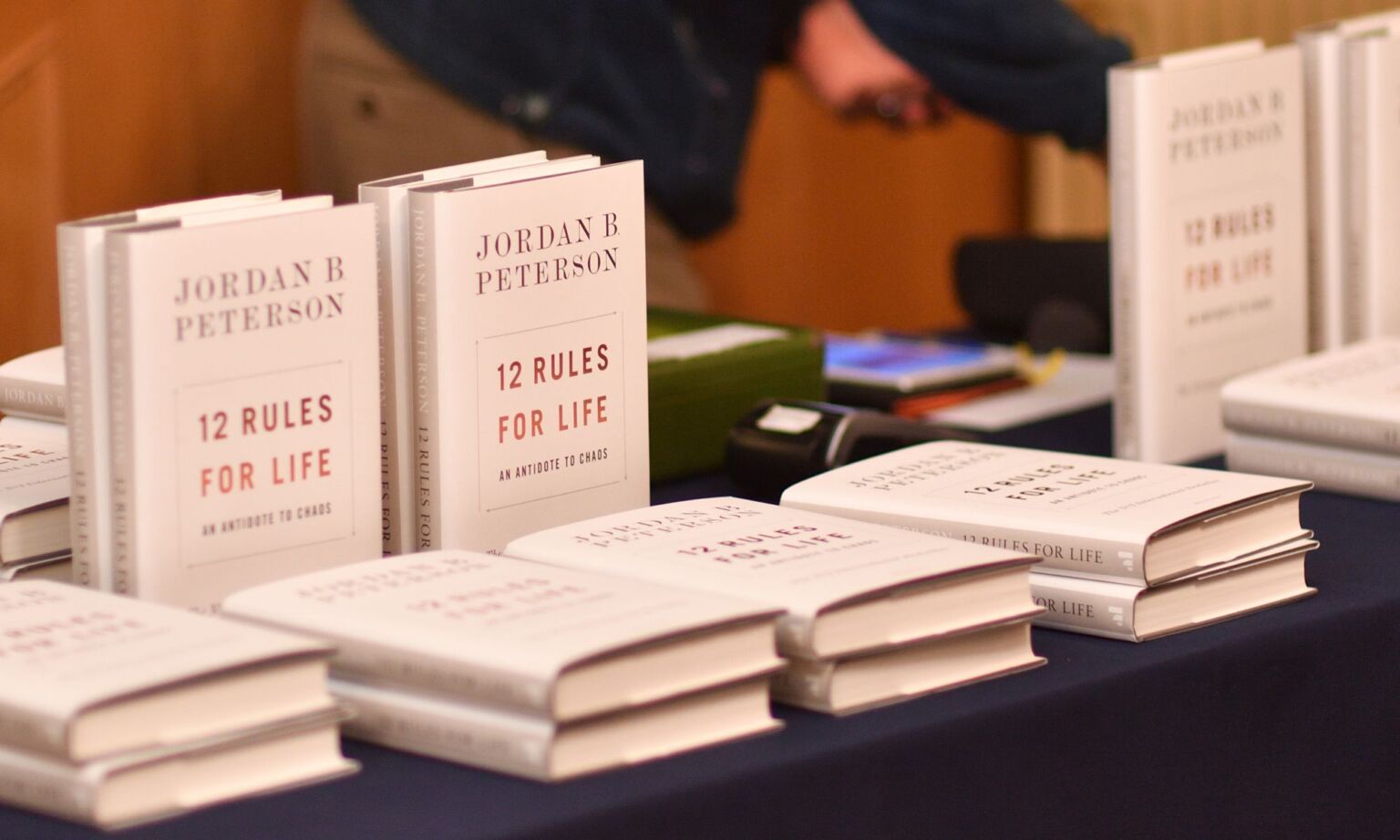

Ironically, this culture of fear inside the Big Five publishers is silencing the very ‘marginalised people’ who, we are repeatedly told, need to be protected from ‘dangerous’ books. As one female editor of colour, who supported her publisher’s decision to publish Jordan Peterson’s Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life, despite an internal protest from her colleagues, explained to me:

‘I’m a feminist. I’m a woman of colour. I’m an editor. I feel a responsibility to respond to things that are wrong. I’ve been in this business a long fucking time. I get it. Times change. We need to evolve. I benefit from that evolution myself. My daughter will benefit from that. But this just feels a bit insane to me now. It feels very frightening. I wish I could just use my voice and say what I feel and publish what I want to publish.’

Around the time agents and their authors began to confront the growing army of sensitivity readers inside American publishers, they also began to notice a new clause that is appearing far more frequently in book contracts. To quote a recent HarperCollins contract, this publisher may terminate a contract if the author’s ‘conduct evidences a lack of due regard for public conventions and morals’.

Much like the language of the 1954 Comics Code, which American publishers created and enforced themselves, the language of this clause is so vague that it gives HarperCollins the right to terminate contracts for virtually any reason. Similar clauses have also appeared in contracts written by Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House and other publishers. The Society of Authors is rightly ‘alarmed at the proliferation of these clauses in publishing contracts’.

As has been the case with sensitivity readers, these clauses seem to have first appeared in contracts for children’s and YA books, under the guise of protecting young readers from harm. They then spread to contracts for adult fiction. Since then, even journalists have been pressured to sign them. Condé Nast, which publishes the New Yorker and Wired, asked its contributors to sign one.

Jeannie Suk Gersen, a law professor at Harvard University, refused to sign hers. As she put it, ‘no person who is engaged in creative expressive activity should be signing one of these’.

Not to be outdone by Condé Nast, the journalists’ trade union, the New York Times Guild, pressured the US paper of record to hire sensitivity readers. Among others, Glenn Greenwald, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who worked with Edward Snowden to expose the National Security Agency’s domestic-surveillance programme, rebuked their demand. A gay progressive, he had choice words for the self-appointed protectors who purport to protect ‘marginalised people’ like him from harm: ‘As creepy as “sensitivity readers” are for fiction writing and other publishing fields, it is indescribably toxic for journalism.’ To put it simply, this ongoing moral panic over literature and non-fiction treats all readers like children.

The Nation forecasted what this would look like. In a 1949 issue, it argued that ‘comic books are an opening wedge. If they can be “purified” – that is, controlled – newspapers, periodicals, books, films, and everything else will follow’. Much like the 1950s, when concerned adults pressured American publishers to self-censor comic-book authors and illustrators, today’s progressives appeal to the overreaching power of big business. When literature is treated as an immoral disease that is spreading like the plague, censorship is seen as the only answer.

In the eyes of many, the Great Awokening is now over – in the first episode of South Park’s 27th season in July, the writers even declared that ‘woke is dead’. But the Great Awokening inside literary culture has shown no signs of slowing down. If anything, things seem to be getting worse. A few months ago, Bloom Books was scheduled to publish Sparrow and Vine by Sophie Lark. This romance novel is about as provocative as a bake sale. However, a controversy still erupted. The readers who had advance copies were outraged about passages in which a fictional character praises Elon Musk. In one passage they hated, the character says, ‘I was inspired by Elon Musk. I use his five-step design process.’ The book was the first in a new romance series. In response to the outrage, Bloom Books cancelled the whole series.

It’s not just America that’s affected, either. The same month Trump was re-elected last year, Norwegian publisher Verbum stopped selling the short-story collection, Christ Legends, by Selma Lagerlöf, a Swedish writer who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1909. Christ Legends, originally published in 1904, has been decried as racist. Halvor Moxnes, a professor at the University of Oslo, said that reading that book felt ‘like a punch in the stomach’. Literary scholar Kari Løvaas said that the book was written ‘in a racist age’. As reported in the Nordic Times, ‘the fact that older works are either censored or not reprinted at all is not unique to Lagerlöf’s works, but is now almost standard procedure when allegedly sexist or racist passages are found’.

Following this Norwegian book controversy from my office in the US, I was reminded of something Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said back in 2020. ‘I think in America the worst kind of censorship is self-censorship, and it is something America is exporting to every part of the world.’ Her remarks at the New Yorker festival were meant to be a warning, not a roadmap.

As one UK agent put it to me, ‘Whatever happens in the US eventually ends up in London because these are global companies’. It eventually ends up in Paris, Melbourne and Berlin, too.

Just last month, a New York Times bestselling author emailed me about That Book Is Dangerous!. This author, who wrote a bestseller about US president Barack Obama, was shocked that my book ever saw the light of day. ‘How the hell did you ever get this published?!’, the email asked me. ‘Thinking about any of this crap just makes me want to vomit… And then on yet another hand, it’s impossible not to think about. Because let’s face it – this stuff is not going away.’

This is sadly true. This climate of censorship is increasingly entrenched within publishing.

In a 1994 essay on the emergence of political correctness during the era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, British cultural theorist Stuart Hall noted that there is a direct correlation between right-wing political power and left-wing cultural power. It is hardly a coincidence that the concern over purportedly racist, homophobic and otherwise insensitive books exploded like a volcano around the time the right in America controlled the Oval Office, the Supreme Court, the Senate, the majority of state governorships and the majority of state chambers and legislatures.

With Donald Trump once again back in the Oval Office, this time with a governmental trifecta, and the desire to bludgeon DEI with a sledgehammer, I imagine the book controversies are going to explode again. The woke might not be able to do anything about the Oval Office, the Supreme Court, the House or the Senate but you can fight the ‘racism’ in that romance novel. In the ashes of the left’s political defeat, cancel culture flourishes.

For those of us who are truly committed to free speech, we now have to contend with legislative censorship from the right and cultural censorship from the left.

As Ray Bradbury put in his coda to Fahrenheit 451, ‘There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches.’

Adam Szetela has a PhD in English from Cornell University. He writes for the Washington Post, the Guardian, Newsweek and other publications. He is the author of That Book Is Dangerous! How Moral Panic, Social Media and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.