Long-read

Sir Stephen Fry: court jester for the cultural elite

This product of the 'alternative' comedy scene is now firmly ensconced in the establishment.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

At 68, Stephen Fry is finally the age he was meant to be. Even though he subscribes to the argument Cyril Connolly advances in Enemies of Promise, that privately educated schoolboys remain locked in a permanent adolescence, he has always been old. At least that’s how it strikes those of us now in our sixties, who have aged with him. As dispassionate observers, we have watched him achieve ‘national treasure’ status, an honour bestowed on such disparate figures as Joanna Lumley and the Windrush generation, by those who decide such things. To them, Fry is as much an institution as the literary giants and characters that formed him: Oscar Wilde, Evelyn Waugh, Agatha Christie, Sherlock Holmes and PG Wodehouse. Of the latter, Fry wrote, ‘in my teenage years, his writings awoke me to the possibilities of language’.

This year, Fry received a knighthood. It was inevitable but perhaps later than he, and the rest of us, expected, given he has been acquainted with the current monarch longer than his tenure as a national treasure. In the 1990s, a joke did the rounds at the BBC: Stephen Fry’s head is so far up Prince Charles’s arse he can see Jonathan Dimbleby’s shoes.

The king and Fry are similar: learned, erudite men to some, yet superior, even arrogant, to others. ‘You have to have arrogance as a comedian in the same way you do as a writer’, Fry said earlier this year. ‘One of the primary arrogances of any writer is to assume that their experience is general and worth sharing.’ In the decades since he came to prominence as Wodehouse’s Jeeves with Hugh Laurie, his comedy partner from Cambridge Footlights days, as Bertie Wooster, there have been many experiences he deemed worthy of sharing on page and screen.

So we know him, and we know so much about him: his teenage kleptomania that led to a stint in prison, his manic depression, his erudition, his celibacy, his homosexuality, his marriage to a spouse 30 years younger who, to us dispassionate observers, could have been his son from a previous marriage. Oscar Wilde, who he portrayed on film in 1997, alerted him to his sexuality during his formative years – ‘his nature was the same as mine’, Fry later reflected. It’s Wilde with whom he’s been compared by those who decide on our national treasures and knighthoods. A comparison Fry rightly dismissed in an interview with the New York Times: ‘To combine Wilde’s insight, acuity, kindness, breadth of reading, wisdom, human folly and divine talent is asking too much of anyone in our culture.’

We know him. Even those of us with no desire to read Stephen Fry’s six novels, 10 works of non-fiction and three autobiographies, or tune in to the abundant BBC projects that helped him amass his millions. This is more from disinterest than dislike. There were other performers that struck us as funnier than Fry and those of a similar pedigree, who came to prominence with the generation of ‘alternative’ comedians who rode a wave in the 1980s.

Speaking of those with a similar pedigree, French and Saunders were provincial middle-class trainee teachers in the right place at the right time, who built a career on camp parody that tickled gay execs in the BBC’s comedy department. Despite the mockney inflection, Ben Elton was the well-connected nephew of historian Sir Geoffrey Elton. As a stand-up comedian he was locked in his own state of arrested development – the hectoring student clinging to the causes and the catchphrases that saw him through his twenties, even though he too is now in his sixties, and old.

It was class that separated this new breed of comedy act and the purveyors of the outmoded humour they replaced. Those of us reared on ITV in the 1970s remember Benny Hill in the background as our mothers flicked through Avon brochures and our fathers licked Green Shield stamps. On weekends, from Granada’s fictional Wheeltappers and Shunters Social Club, Bernard Manning’s blue jokes sent us off to bed on a Saturday night. As a puerile, passive viewer, I felt little affection for the northern comics and the saucy slapstick then popular, but none at all for the student politics and RAG-week-style routines that were seeing the old guard off.

The working-class comedians who commandeered light entertainment at the time had honed their craft at northern social and working men’s clubs. The emerging generation of comics were graduates who rose rapidly from London’s Comedy Store or Cambridge Footlights to front series for the BBC and a nascent Channel 4, where their peers at university had taken up roles as producers and commissioning editors. Despite the ‘alternative’ tag, they were very much a product of the establishment. This was particularly true of Stephen Fry and Emma Thompson – the latter undoubtedly being the most entitled of this new order, with her mother an actress, her father a BBC veteran (he adapted and narrated The Magic Roundabout), and the obligatory high-end Hampstead upbringing before Cambridge called.

Fry and Thompson are inextricably linked by elite schools, Hampstead (Fry’s place of birth, too), Cambridge, the BBC and an affiliation with the man who would be king. Now Fry is a Sir, Thompson is a Dame and the views they proffer on issues of the day have become more noteworthy than the work they produce.

This is true of their fellow travellers from that distant age who, in any other industry, would be retired and receiving their pension. Dawn French can be found giving her take on Hamas and Israel on Instagram. Jennifer Saunders will be airing her views on Nigel Farage and Reform UK on Channel 4’s Gogglebox.

In a slow week for Armageddon earlier this summer, Dame Emma Thompson took a break from climate-change activism to suggest that sex should be available on the NHS. She even adopted that fretful Lady Bountiful look that’s as evident in her roles as Forster’s Margaret Schlegel, Austen’s Elinor Dashwood, as it was when acting in a Marks & Spencer ad alongside Doreen Lawrence. At roughly the same time, Stephen Fry accused JK Rowling of being radicalised by ‘TERFs’ for challenging the motives of the transgender lobby.

His use of the ugly ‘TERF’ was an odd choice for one so enthralled by the beauty of the English language (he examined etymology in the BBC series, Fry’s Planet Word in 2011). I guess it’s in keeping with the fluffy phrases he falls back on during chat-show interviews, when referring to sex or genitalia.

Like the BBC, Rowling helped Sir Stephen top up his millions. He narrates the Harry Potter audiobooks and previously commended her on her Potter fable, as it taps into the stories and ancient myths that captivated him as a child. Fry has written about these in Mythos (2017) and in several books since, the most recent being Odyssey (2024). He maintains that by understanding ancient myths, we appreciate the eternal truths central to human behaviour. ‘Morals are not eternal verities’, he says. ‘They are what we think of as right now.’ This could explain his reaction to critics of transgenderism, hinting that they are simply following contemporary conventions and morals. But surely biological sex is an eternal verity and gender identity isn’t?

The ancient past and near future are each an obsession for Fry. He was early to the World Wide Web, and first among his friends to embrace email. He jettisoned Twitter after Elon Musk took the helm and transformed it into X. While Fry is a vocal champion of free speech, it’s a courtesy he doesn’t extend to everyone. As he put it in an interview last year, social media are responsible for ‘all kinds of beastly and horrific things that coloured this utopian dream of an internet connecting people and gave it nothing but horror and despair’.

But beyond the trolls and the conspiracy theorists, it provides a platform for the voices of a marginalised majority who interpret major events differently from the establishment Fry is loyal to: the BBC, the monarchy, the Labour Party. For the latter’s leaders, from Neil Kinnock to Gordon Brown, he wrote speeches. These institutions belittle or ignore the issues central to the lives of a disgruntled public heading towards the Howard Beale moment in Network: ‘I’m mad as hell, and I’m not taking it any more.’ And who knows, something like a revolution will not be televised, but it might be forged on social media and on the streets of London and Essex.

The English language Stephen Fry loves is being doctored. The illegal immigration that is proving catastrophic is now ‘irregular immigration’. Those murdered by Islamists have ‘lost their lives’. The ideology behind the murders is secondary to the need for our multi-faith community to heal, and not be divided by hate. Seldom has this been more offensive and overt than with the feeble commemorative notices marking the 20th anniversary of the London bombings in 2005 this July, from the prime minister, the king and the London mayor. The language we use, and which Fry gestured towards with his attack on Rowling, is also under threat with Labour’s planned ‘banter ban’, intended for pubs and offices, as well as its proposed Islamophobia definition, which aims to silence criticism of Islam.

‘I am a lover of truth’, Fry tells us, ‘a worshipper of freedom, a celebrant at the altar of language and purity and tolerance’. Yet, we have heard little of his reaction to these developments, despite his willingness to speak out on other issues of the day.

He did provide Jordan Peterson with some brilliant back up at Toronto’s Munk Debate in 2018, when they argued against ‘political correctness’ – a term that doesn’t sufficiently sum up the moronic mindset it addresses, and the lethal moment it has led us to. When Fry takes time away from the past and the future to comment on the present, is it an attempt at relevance or simply part of the performance, part of the public persona that will persist even if the projects dry up? ‘I am always for an audience’, Fry said not so long ago. ‘Every time I write a phrase – even when I’m speaking now, I’m thinking of people at home listening… I’m so aware of it.’

To his audience he, like the current king, remains a quaint character from another age – the crusty don, the confirmed bachelor, or the eccentric uncle, funny to some, unfunny to others. Fry maintains, modestly, that he has never had the capacity to be an intellectual or an academic. When The Times described him as an ‘avuncular public intellectual’ in 2021, he responded with: ‘Oh my lordy lord. Avuncular gives me great pleasure. But I disavow “intellectual”, just as I disavow “artist”. I am, I think, an entertainer, impure and simple.’

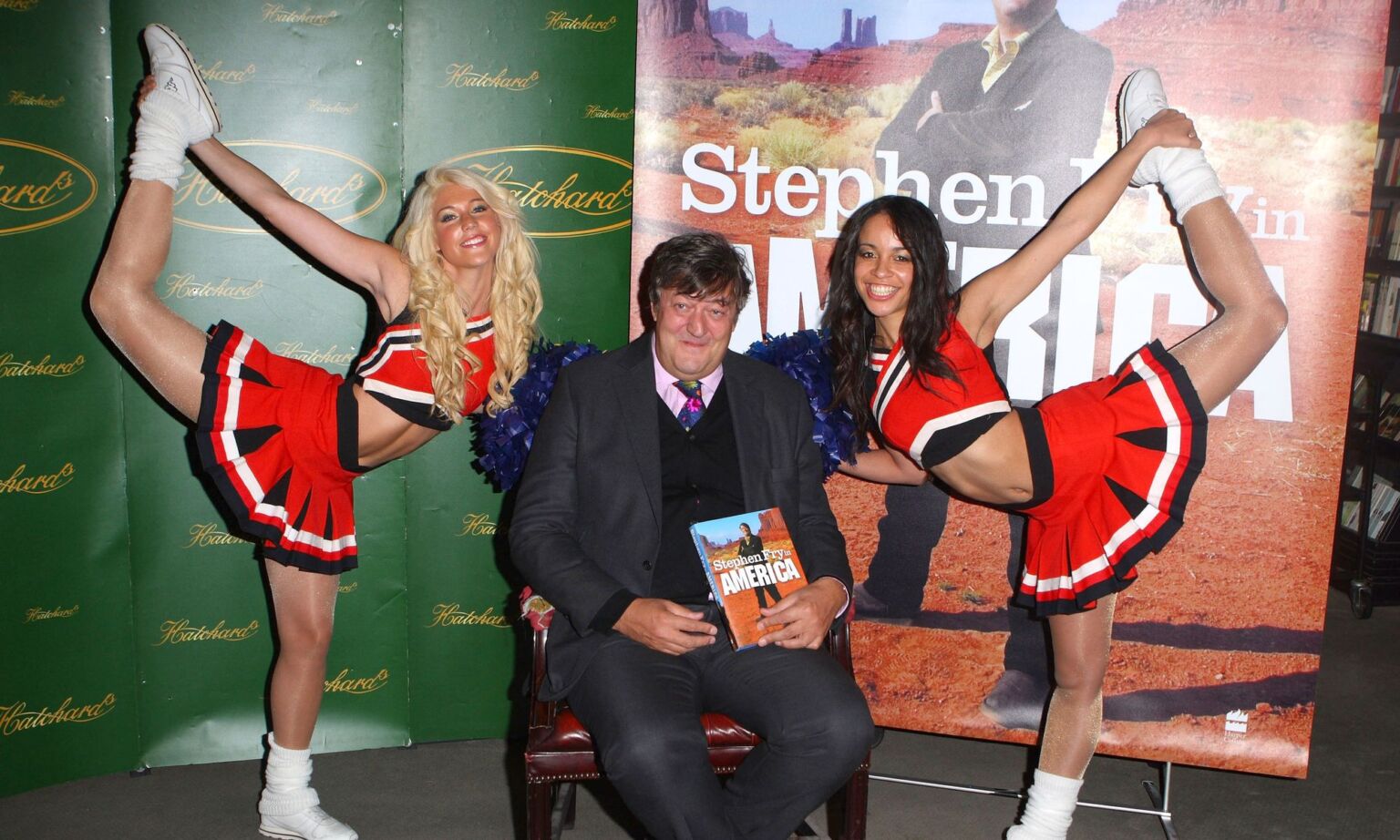

This has enabled him to write, act, and front series and documentaries on travel (Stephen Fry In America), depression (Stephen Fry: The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive), homosexuality (Stephen Fry: Out There) and maybe one day Stephen Fry on ‘hats’, a project that has been a work-in-progress for a while, and an ambition for longer. Whatever the whim, a prominent publisher or our public broadcaster will be willing to finance it as a book, radio series or television programme. He has, in marketing speak, ‘reach’. Before Fry made his excuses and left Twitter, he had 13million followers.

He had flounced off Twitter on several occasions because he was frequently criticised and challenged by the public. But it was that pesky democracy that irked him over Brexit. In 2023, he referred to it as ‘a clown car crash and you can’t help being amused by it’. Prior to the EU referendum, Emma Thompson said we should be opening borders rather than closing them, an issue that concerned her as much as the prospect of Tesco Metro opening in her Hampstead village, which, naturally, she campaigned against. Thompson informed us that Britain was ‘a cake-filled, misery-laden, grey old island’, as she bought a home in Venice. Yet like Fry, she is a product and a champion of a certain type of England, one in which the BBC, Oxbridge and – despite her paternalistic, leftish leanings – the monarchy holds sway. Such an England appealed to the young Stephen Fry when he was a proud old school, one nation Tory, attending Conservative fêtes and whist drives. This was before the wind changed – ‘The wind’s name was Margaret Thatcher’, he says. After Thatcher, supporting the Labour Party became obligatory, expedient and a career move for the comic performers of Fry’s generation.

Class is therefore central to the England that appeals to Sir Stephen and Dame Emma. One far more immersed in nostalgia than the Britain of Brexit supporters, who are responding to very contemporary challenges. For many Leave voters, England has become ‘misery-laden’ because of the migration crisis, among other things. For many natives it remains the only home they have known, and the only home they may ever know. Which is why they are angry at those intent on destroying it, and their relation to it.

A home in Albion’s pastoral idyll features in the fantasy that Fry has often allowed himself, when musing on the life he might have led in a house, a very big house in the country – ‘not necessarily a grand house, certainly not Downton Abbey or anything, but enough to have hens who laid eggs and that every year I would make pickles and jams and that my only career would be a writer’. It’s the society he longed to join when he first encountered the worlds Evelyn Waugh and PG Wodehouse were writing about. Fry never became the lord of the manor, but having arrived at the age he was always meant to be, two years away from 70, consolation has come by way of a knighthood. An honour that wasn’t conferred on Wodehouse until the month before his death, aged 93, and one that Waugh expected but never received.

In that, at least, Fry has surpassed his heroes.

Michael Collins is a writer, journalist and broadcaster. He is the author of The Likes Of Us: A Biography of the White Working Class.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.