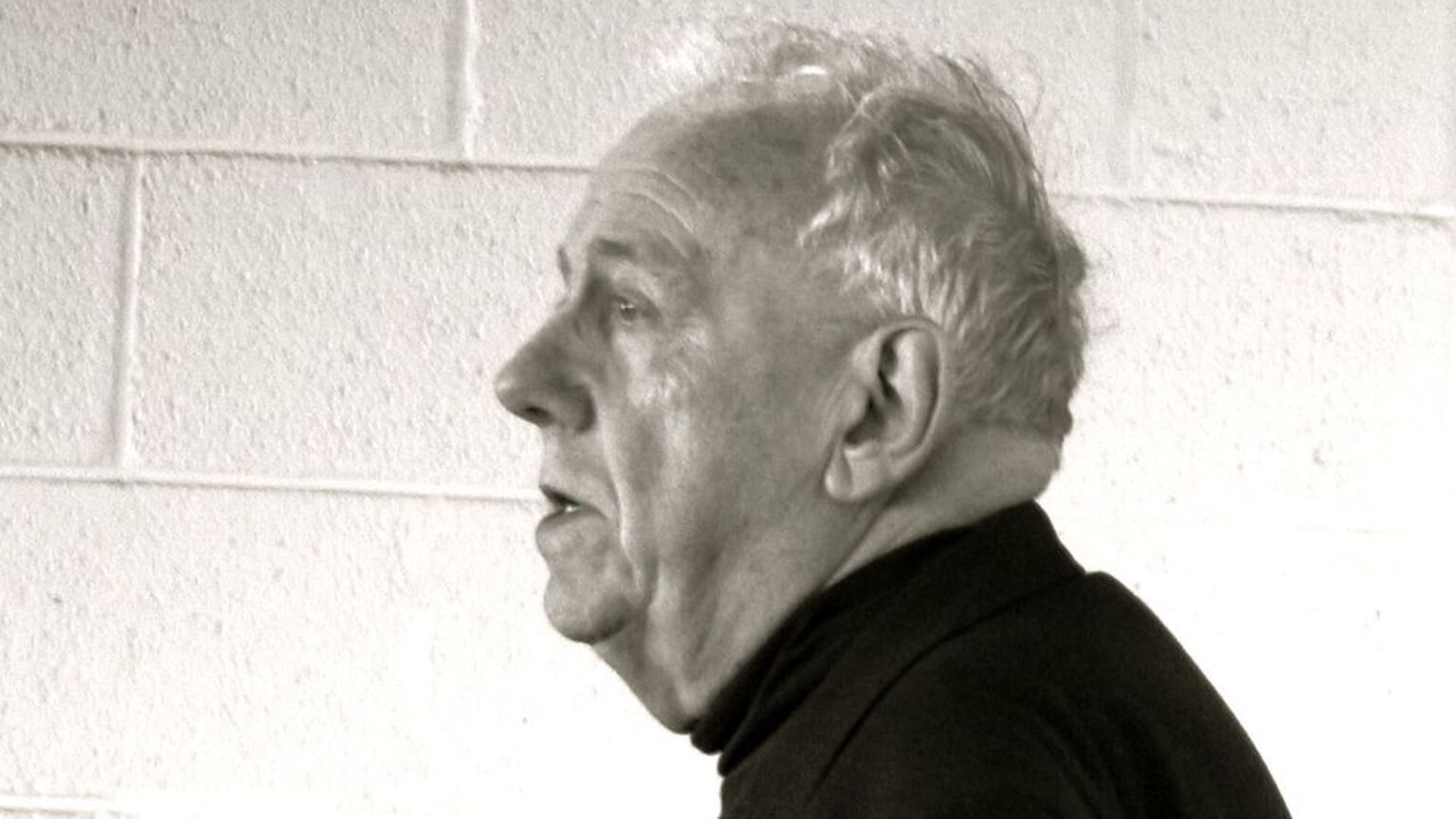

Alasdair MacIntyre: a thinker for our disillusioned times

The late philosopher gave form to our innate yearning for shared values and a common sense of purpose.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Alasdair MacIntyre was a philosopher of his time and, on the occasion of his death last week at the age of 96, a thinker for our times. His writings came to prominence in an era in which the tenets of the Enlightenment, and their realisation in modernity, were coming under fierce attack. His belief that complacent liberalism and amoral capitalism had each exalted individualism at the expense of a sense of community still resonates today.

His signature work, After Virtue, was published in 1981, and articulated sentiments then emergent in Anglophone academia. Informed by the work of a remarkably influential constellation of French thinkers, such as Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, there was a growing belief that the Enlightenment had been a mistake on two counts. Firstly, it was judged to have been hopelessly ambitious in its belief that objective truth could be attained, or that universal ethics could even exist. Secondly, it was deemed to have had catastrophic consequences. Colonialism, racism and even the Holocaust were believed to be rooted in the Enlightenment compulsion to rationalise and classify, to arrange the world into hierarchies and categories.

MacIntyre largely agreed with this judgement. He felt that the Enlightenment’s notion of universalist ethics was ahistoric and baseless, and that its belief in ‘good’ and ‘evil’ was an illusion, insofar as there was no objective standard on which to base morality. Its conceitedness and myopic materialism had resulted in exploitation, alienation and spiritual impoverishment. MacIntyre honed in especially on the pernicious influence of bureaucracy and scientism. An emphasis on individual freedom had descended into atomised individualism and the dissolution of a collective self.

He was a chief exponent of the derisory term, ‘the Enlightenment project’ – a go-to phrase for advocates of postmodernism in the 1980s. And like so many of postmodernism’s leading lights, MacIntyre had himself been a Marxist in the 1950s and 1960s, only for events inside and outside the academy to throw into doubt the Enlightenment principles on which Marxism had been built. An earlier work, Against the Self-Images of the Age (1971), had criticised both Christianity and Marxism for their failure to establish adequate foundations for morality, or ‘to provide the light that our individual and social lives need’.

As with Foucault and Derrida, MacIntyre was an assiduous reader of Friedrich Nietzsche. Like them, he followed the German in asking: with the death of God, who is there to tell us what is right or wrong? On what authority do we base our system of morality? In A Short History of Ethics (1966), MacIntyre replied with the uncomfortable but inevitable answer – that systems of ethics are inevitably particular to their time and place, and thus morality is necessarily subjective and contingent.

While some ethical philosophers such as Richard Rorty embraced the new postmodern reality of the 1980s as a liberation, others, especially MacIntyre, despaired. He spoke of a grim fate should we continue on the same forlorn trajectory that left us now teetering on the abyss of nihilism. As he wrote in After Virtue: ‘either one must follow through the aspirations and the collapse of the different versions of the Enlightenment project until there remains only the Nietzschean diagnosis… or one must hold that the Enlightenment project was not only mistaken, but should never have been commenced in the first place.’

In order to rectify the defects of modernity, he argued that we ought to reject the ‘ethos’ of the modern world, with its ‘liberal individualism’ and ‘emotivist culture’ – a culture that reduced ethics either to utilitarian instrumentalism, judging actions on account of their effectiveness, or as a mere expression of personal preference and choice.

The unfettered individualism and hedonism of modernity that MacIntyre derided might, superficially, explain his conversion in later life to Roman Catholicism. But there was more to it than that. It was a decision also informed by his life-long interest in St Thomas Aquinas and, in turn, the inspiration both had taken from Aristotle.

MacIntyre’s response to the failure of the Enlightenment project was to return to the Ancient Greek principle of virtue, to a life founded on the principle of telos, a word that denoted both meaning and aim. In order to live a good life, said Aristotle, the individual should proceed with a sense of purpose, cultivate the faculty of wisdom, and conduct himself or herself in accordance with the innate (albeit unspecified) ‘good’ characteristics endowed by nature.

In MacIntyre’s interpretation, this necessitated living according to custom and tradition, through education, participation and mutual deliberation in one’s ineluctable social setting. The Enlightenment had misunderstood the human subject by reducing it to no more than a rational agent, thereby stripping man of his social identity, including his superstitions, rituals and embeddedness in history. Indeed, it is often in the realm of stories and untruths that we grasp reality more fully. Humans are creatures who look to narratives to make sense of the world: ‘man is in his actions and practice, as well as in his fictions, essentially a story-telling animal. He is not essentially, but becomes through his history, a teller of stories that aspire to truth.’

Although he rejected the terms, MacIntyre came to be associated with communitarianism and virtue ethics, with their eschewal of individualism and liberalism. His ostensible revolt against reason and his exaltation of tradition made him appear, more simply, as an anti-modernist. Bernard Williams called After Virtue a ‘brilliant nostalgic fantasy’, and MacIntyre was often accused of moral relativism. While he did contend that different conceptual frameworks and ethical systems were incommensurable, some modes of seeing the world could be nonetheless more successful, worthy and persuasive than others. Indeed, he sought to show how the Aristotelian perspective could teach us why Enlightenment thinking had failed.

In this, After Virtue caught the spirit of the age, as did its successors, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988) and Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990). His thinking continues to resonate, albeit in two rather different settings: among both hyper-liberals who inherited a postmodern rejection of Enlightenment reason, and reject it as little more than a Eurocentric power-knowledge system; and, even more strongly, among those engaged in the populist revolt against the malign aspects of a modern world that MacIntyre decried. A world, that is, that seems to be arranged in the interests of liberal universalists and free-marketeer globalists, who regard societies foremost from a macro-economic perspective.

Alasdair MacIntyre’s work did not so much hark back to ancient values, but to timeless ones. And therein lies the source of his appeal and importance. He gave form to our innate yearning for shared values and a common sense of purpose.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, is published by Societas.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.