The Gregg Wallace scandal has revealed the media’s skewed priorities

Why is obnoxious banter being lumped in with allegations of groping?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

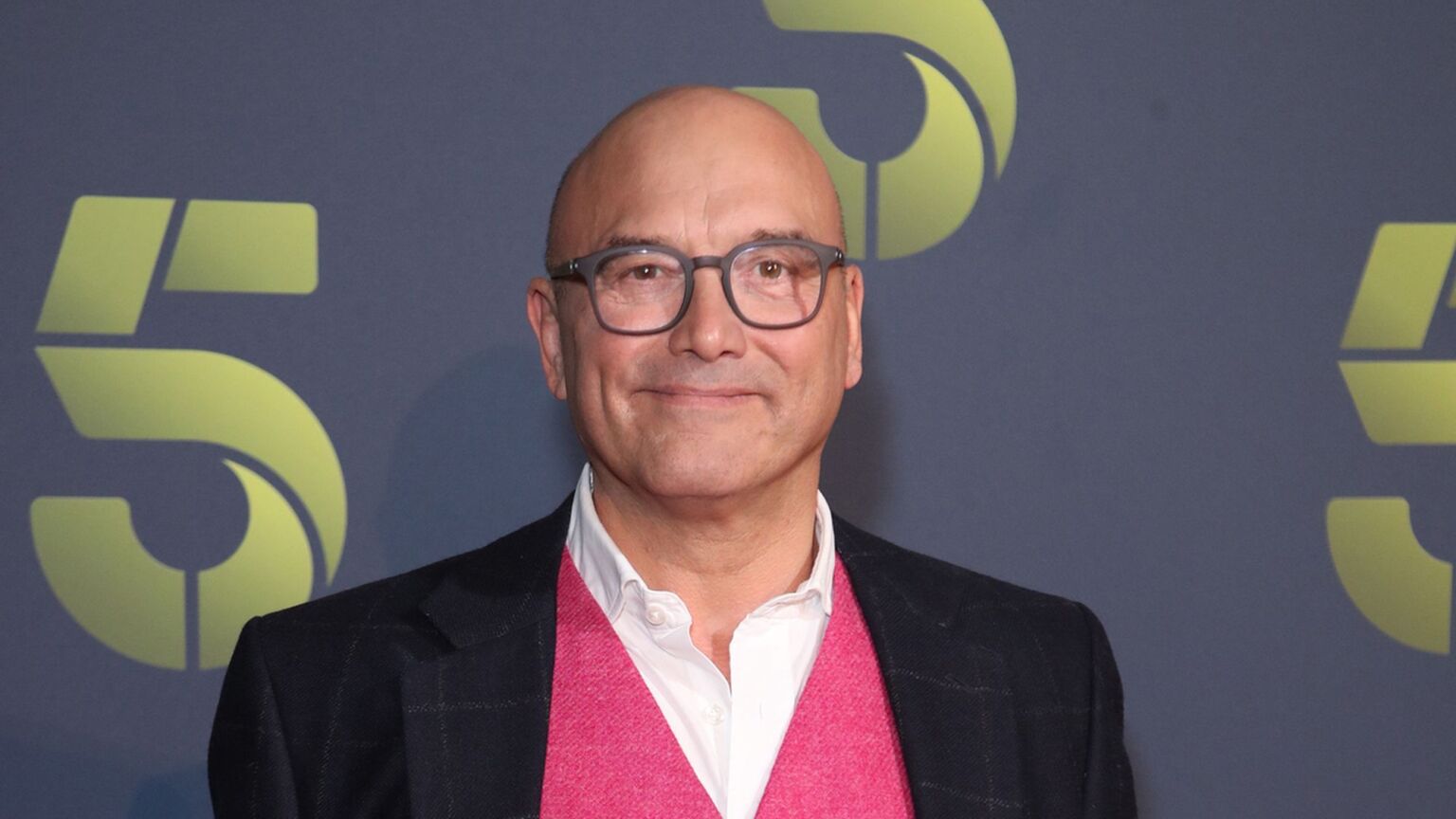

So that’s it. Following days of round-the-clock coverage of all the ways in which presenter Gregg Wallace makes women feel uncomfortable, the BBC announced on Tuesday that it has pulled the plug on two MasterChef Christmas specials (while still allowing the current series of MasterChef: The Professionals to finish its run as planned).

Downing Street’s condemnation of Wallace’s cack-handed non-apology as ‘completely inappropriate and misogynistic’ seems to have been the final straw for the beleaguered corporation. How fortunate for us viewers that UK government ministers have nothing better to do with their time than comment on the latest sex scandal. Only, in Wallace’s case, this is all scandal and, seemingly, no sex.

As Luke Gittos explains on spiked this week, the most serious allegations against Wallace are that he ‘groped’ three women on the set of MasterChef, ‘while the cameras were rolling’ and then ‘yelled abuse’ at them. This needs to be investigated thoroughly and, if found guilty, Wallace should face the consequences of his actions.

Yet it’s notable how little this alleged ‘groping’ offence features in the acres of press interest his behaviour has generated. Instead, the media have focussed mainly on accusations that he behaves in a way that is ‘unprofessional’ and ‘inappropriate’.

There are claims Wallace joked about rape, danced naked – save for a strategically placed sock – and mimed a sex act. If this is supposed to be humour, it’s not to my taste. Even in his own Instagram videos, Wallace comes across as a sleazy, sexist, insensitive boor.

Being on set with him ‘felt like you were around a dinosaur’, according to Ulrika Jonsson. Former TV presenter Melanie Sykes called out Wallace’s ‘sexually inappropriate conduct’ in her autobiography published last year. She writes that her experience with the presenter ‘finally helped me decide to end my television career once and for all’. In a recent YouTube video, she explains: ‘I didn’t really like him being around really because it’s all about vibrations and energy.’

Most of the complainants take a similar line. They say the guy’s a creep. That he makes women feel ‘uncomfortable’. Certainly that’s not nice, but it’s hardly illegal.

Horrible bosses and unpleasant colleagues – even ones who make people feel demeaned and humiliated, as Wallace is alleged to have done – are as old as the world of work itself. It’s one reason why trade unions developed, allowing employees to collectively deal with problems at work. It’s also why we have employment laws criminalising sexual harassment, discrimination and a host of other unfair workplace practices. But no unions or laws can protect against bad vibes, negative energy and making people feel uncomfortable. Unlike pay or working hours, feeling uncomfortable is entirely subjective.

The broader discussion about feeling uncomfortable in the workplace that the Wallace furore has unwittingly prompted says as much about changed attitudes to employment as it does about one presenter’s lewd sense of humour. Not that long ago, no one gave a toss about how people felt about their work. The idea that work was meant to be emotionally satisfying, or make people feel good about themselves, or even ‘comfortable’, was for the birds. Even today, work for most people means putting in the hours in order to get paid. Feelings don’t come into it. Sykes criticises Wallace for ‘barking orders’. She may not like it but having orders barked at you is an everyday occurrence for millions of people who work in restaurants, bars or on building sites.

In the past, talk of ‘safety’ at work meant physical safety. It meant not getting crushed down a mine or losing a limb on a production line. Now it means emotional safety, or being protected from anything deemed to be offensive or upsetting.

Furthermore, rather than employees banding together to demand better working conditions, they ask managers to protect them from each other. Bosses love this. They insist people ‘bring their whole selves to work’. Some branches of the civil service apparently start meetings with ‘lengthy emotional check-ins’ so people can divulge their inner-most feelings at the start of the working day. The problem is, some people’s ‘whole self’ is Gregg Wallace.

Once, people who made stupid remarks were told to belt up. Idiotic jokes warranted an eye-roll. Of course, banter could also make work just about bearable. But in today’s workplace, banter is out and emotional check-ins are in. Solidarity and standing up for yourself are frowned on, but running to the boss with a complaint against a colleague is considered brave.

Stranger still, accusations of ‘inappropriate’ behaviour are apparently worth days of front-page news coverage, but lay-offs of thousands of workers barely merit an inside column. ‘Is Gregg Wallace the most obnoxious man in Britain?’, asked one Telegraph journalist this week. That this question is being asked at all is a sign of our complete loss of perspective.

Joanna Williams is a spiked columnist and author of How Woke Won. She is a visiting fellow at Mathias Corvinus Collegium in Hungary.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.