We still need to reckon with the folly of lockdown

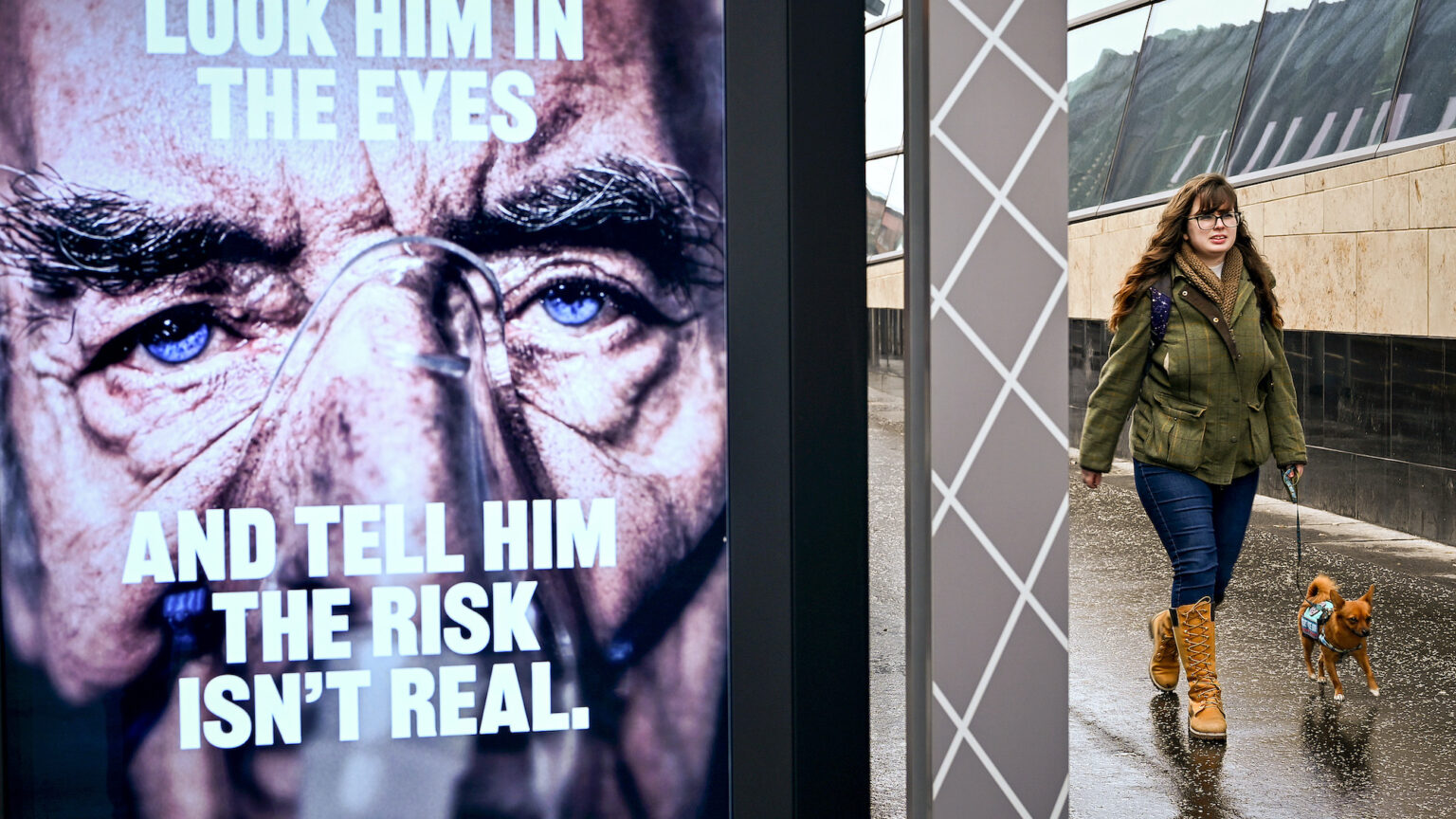

The Covid inquiry has exposed the widespread harm caused by the UK’s authoritarian restrictions.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In July, Lady Hallett’s Covid inquiry published its first interim report, examining the ‘resilience and preparedness’ of the UK in its pandemic response. Its publication was widely welcomed in the media, not least because it castigated former health secretaries Matt Hancock and Jeremy Hunt, former Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon and others who today enjoy little public sympathy.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the report was its open recognition of the harm caused by lockdown. It acknowledges that lockdown was not part of the UK’s planned pandemic response, but an untested policy adopted on the hoof. According to the inquiry, this meant that there was no time to scrutinise its potential consequences – consequences that we are still living with today. The economic cost of lockdown is estimated to be £376 billion. And that doesn’t account for the unquantifiable damage it has caused to healthcare, education, the arts and beyond. Fears that Lady Hallett would parrot the line that ‘we should have locked down sooner and harder’ have thankfully been allayed.

However, the report is far from flawless. Lady Hallett does assert another oft-heard claim: that the UK planned for the ‘wrong’ pandemic – for an influenza outbreak rather than a coronavirus – and that two Asian countries, South Korea and Taiwan, fared better than us. Their success in avoiding national lockdowns was achieved, we are told, because they closed their borders and had high-capacity test-and-trace systems ready to roll out from the start of the pandemic. This view ought to be challenged.

The UK’s pre-pandemic planning is detailed in the 2011 UK Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Strategy. It is very much a ‘keep calm and carry on’ approach, accepting that a pandemic will bring mass casualties and that, as in all past pandemics, these must be endured. It envisages the government’s role as simply to mitigate the harm and protect the vulnerable until the virus finds its own level. The notion that this plan was exclusive to influenza, the likelier pathogen, is easily dismissed. Virologists still debate whether the ‘Russian Flu’ of 1889-94 was an influenza or an emergent coronavirus. There would be no such debate if two respiratory viruses caused obviously different types of pandemics.

The 2011 strategy was briefly adopted in March 2020, with chief scientific adviser Patrick Vallance declaring the need to build up ‘herd immunity’ in the population. It was abandoned and replaced with a lockdown approach within a few weeks. Lady Hallett is sketchy on the reasons why, noting only Matt Hancock’s assertion that the earlier strategy was ‘woefully inadequate’. I recall several reasons for the sudden change of approach.

Firstly, there was the fear, exacerbated by modelling from Imperial College London, that the NHS was about to be overwhelmed. Secondly, France threatened to restrict transport to and from the UK unless we changed policy. Thirdly, a hysterical media demanded that we follow other European countries into lockdown. Then, when Boris Johnson’s government opted for a lockdown, it pivoted from encouraging calm to fuelling panic with its own propaganda. None of these crucial developments was even mentioned in Lady Hallett’s report.

Was the switch to lockdown warranted? This too remains unaddressed in the report. There is ample evidence that the UK’s first Covid-19 wave was already peaking in mid-March, before the first lockdown even began. We could have ridden out the storm. Sweden, which Lady Hallett does not mention, stuck with a plan resembling the UK’s 2011 strategy throughout the pandemic and emerged with the lowest total excess mortality of anywhere in Europe between 2020 and 2023. It also experienced less societal damage and accrued less pandemic debt per capita than the UK and the EU average.

As for Korea and Taiwan’s mass-testing strategy, does Lady Hallett seriously think that this strategy would work in Britain? As I’ve spelt out previously on spiked, South Korea’s scheme was particularly intrusive. Following a May 2020 outbreak in Seoul, 41,620 tests were performed on nightclub visitors and their contacts in order to identify just 246 cases. This includes Koreans who were five- or six-times removed from the original clubgoers. Back in early 2020, the testing infrastructure for this simply did not exist. Even now with the pandemic behind us, the cynicism many Britons feel towards the events of 2020 means that a lot of people would simply not comply in the event of a future outbreak.

What’s more, although Taiwan and South Korea avoided the spring 2020 death spike, they hardly escaped the virus unscathed. Excess deaths continued to rise in the following two years, in most months at higher rates than the UK. Excessive fear of the virus seems to have become permanent in both countries. My wife, who is Taiwanese Chinese and presently caring for her mother in Taipei told me recently:

‘In the past three weeks, Covid-19 has become a wide concern again. Case numbers are up, severe ones, too. It’s high in the news. The government recommends more vaccinations. Most people are wearing masks indoors, particularly on public transport. At the hospital, I was among a handful without a mask.’

Taiwan News corroborates this, stating last month that Taiwan is experiencing its ‘sixth wave of Omicron’. At least the UK has managed to move on from this kind of hysteria.

Despite these flaws, Hallett does make some good recommendations. She highlights the dangers of ‘groupthink’ and suggests that future pandemic responses should adopt ‘red teams’ – groups of dissenting non-experts trained in critical thinking. This is welcome, and will be particularly important when momentous decisions need to be made quickly. Also wise is Hallett’s recommendation that the government should be more open to ‘unconventional thinking’, though it is troubling that her Covid inquiry hasn’t always followed this advice. Just look at its shoddy treatment of leading lockdown-sceptic Carl Heneghan last year. His only involvement with the Covid response was a single Zoom meeting with Johnson in September 2020, in which he called for ‘focussed protection’ of the vulnerable and an end to lockdowns. Yet the inquiry’s questioning was hostile, adversarial and sneering.

Few would also dispute Lady Hallett’s view that too many different groups had overlapping responsibilities during the pandemic, complicating the response. But her solution to this issue is deeply troubling. Hallet proposes a ‘single, independent statutory body responsible for whole-system preparedness and response’. This organisation would presumably be pan-UK, with powers to ‘consult widely with experts in the field of preparedness and resilience, and the voluntary, community and social sector [to] provide strategic advice to the government and make recommendations’. In other words, another unaccountable quango.

All that said, the report could have been much worse. It could have supported the fantasists, like Matt Hancock, who believe that earlier and harsher lockdowns were the answer. But perhaps, and here’s a heretical thought, the 2011 strategy was at least honest, and we should have stuck with it. We are prey to these sorts of pandemics every two or three generations, and there really isn’t too much you can do about it – except at the margins.

After all, we cannot say for sure what the next pandemic will look like. But what is certain is that pandemics prior to Covid, when the government response was far less authoritarian, caused far less lasting harm to society.

David Livermore is a professorial fellow at the University of East Anglia.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.