Libraries are being destroyed from within

The public does not need protection from ‘problematic’ texts.

Libraries have always borne the brunt of censorship. Typically this has come from officials and members of the public who have taken issue with certain texts. However, in recent times the impulse to police a library’s collection has come from the inside. Librarians and curators are now taking it upon themselves to try to protect readers from the supposed threat posed by certain books.

The latest case of censorious librarians comes from the Cambridge University Library, which is one of Britain’s six legal-deposit libraries. Since 1662, readers have had the right to request and receive a copy of everything that has been published in the UK. However, this culture of open research seems unlikely to survive our identitarian era.

The Telegraph reported earlier this month that Cambridge University Library sent a memo to the librarians in Cambridge’s 31 colleges, telling them: ‘We would like to hear from colleagues across Cambridge about any books you have had flagged to you as problematic (for any reason, not just in connection with decolonisation issues), so that we can compile a list of examples on the Cambridge Librarians intranet and think the problem through in more detail on the basis of that list.’

The word ‘problematic’ is a self-conscious euphemism, which in this case refers to books that are deemed objectionable and offensive. The library memo explicitly mentions ‘decolonisation’ – the movement calling for fewer texts by white, Western and European authors to appear on university reading lists – but we can assume that a text would be deemed ‘problematic’ if it offends woke sensibilities for any reason.

The memo also called on Cambridge colleges to inform the main university library of ‘anything you are already doing in your library to address this or similar issues’ to be sent to a special ‘decolonisation’ email address. One of these libraries, that of Pembroke College, immediately complied and emailed staff promising that it was ‘working to better support readers’. The implication here is that readers (university students, no less) are unlikely to be able to cope with the threat posed by problematic texts.

It should go without saying that it is not a library’s job to designate which books in its collection are problematic. Academics and their students ought to have the moral and intellectual maturity to deal with the content of the books they read.

Responding to the Telegraph report, a Cambridge University Library spokesman insisted that this is not a form of censorship. ‘Cambridge University Libraries do not censor, blacklist or remove content unless the content is illegal under UK law’, he said. Instead, Cambridge says that its aim is to create a kind of catalogue of problematic texts, with the goal of drawing up materials to help ‘support’ readers who might be affected by them. So formally speaking, this is not censorship. Arguably though, it represents something even worse than that – it is an attempt to control how readers react to texts.

It suggests that librarians have started to behave like therapists, obsessed with micromanaging the thoughts and feelings of readers. Many have tried their utmost to present the collections for which they are responsible as a risk to the general public’s wellbeing.

Similar moves are afoot in the US, also in the name of ‘decolonisation’. In 2021, the American Library Association organised a webinar titled ‘Decolonising the Catalogue: Anti-Racist Description Practices from Authority Records to Discovery Layers’. This webinar aimed to discuss efforts to ‘remap problematic, outdated and offensive’ catalogue subject headings. In line with this approach, the library at Columbia University issued a statement later in 2021 titled ‘On Outdated and Harmful Language in Library of Congress Subject Headings’.

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, DC is taking a similar approach. NARA issued a statement in 2022 to warn that its ‘catalogue and webpages contain some content that may be harmful or difficult to view’. The document asserted that: ‘NARA’s records span the history of the United States, and it is our charge to preserve and make available these historical records. As a result, some of the materials presented here may reflect outdated, biased, offensive and possibly violent views and opinions.’

It is mind-boggling that NARA felt the need to remind its readers that a collection of historical documents may reflect outdated views. What else should one expect when inspecting centuries-old texts?

With important institutions like the National Archives and university libraries seeking to ward their readers away from ‘problematic’ texts, it was only a matter of time before ordinary public libraries followed suit. Already in England numerous local libraries have removed books that are critical of gender ideology, for instance.

The practice of hiding controversial books from the public has the full support of many officials involved in running public libraries. Guidance issued in 2022 by Calderdale Council, for example, advised that action be taken to stop LGBT people seeing ‘offensive’ gender-critical books, by hiding them from view and limiting the number of stock. It states that ‘we, along with many in the LGBTIQ+ community, find these books offensive’. Therefore, the twisted logic goes, no one else can be allowed to view them.

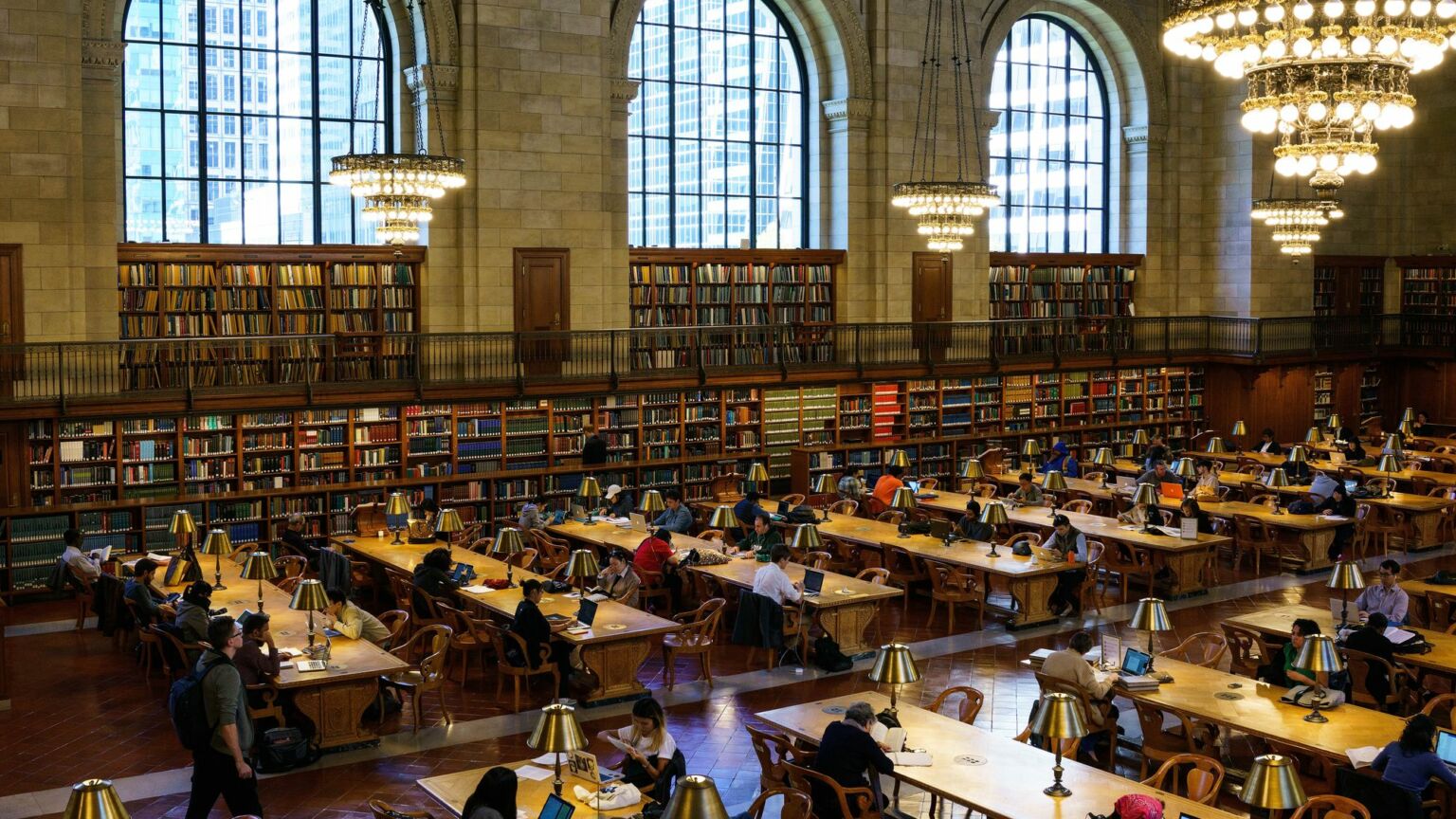

Once upon a time the library was a place of refuge, where readers could get away from the noisy conflicts of public life. Unfortunately, the library has become yet another battleground in the culture war. Not only does this kind of censorship infantilise readers, but it also threatens people’s freedom to choose which texts they read and what ideas they are exposed to.

Reading should be a journey of discovery, where people find out for themselves how they feel about the books that they read. There are no problematic books, only problematic censors.

Frank Furedi is the executive director of the think-tank, MCC-Brussels.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.