Andrew Malkinson: the end of the presumption of innocence

An obsession with driving up conviction rates has warped the priorities of the justice system.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

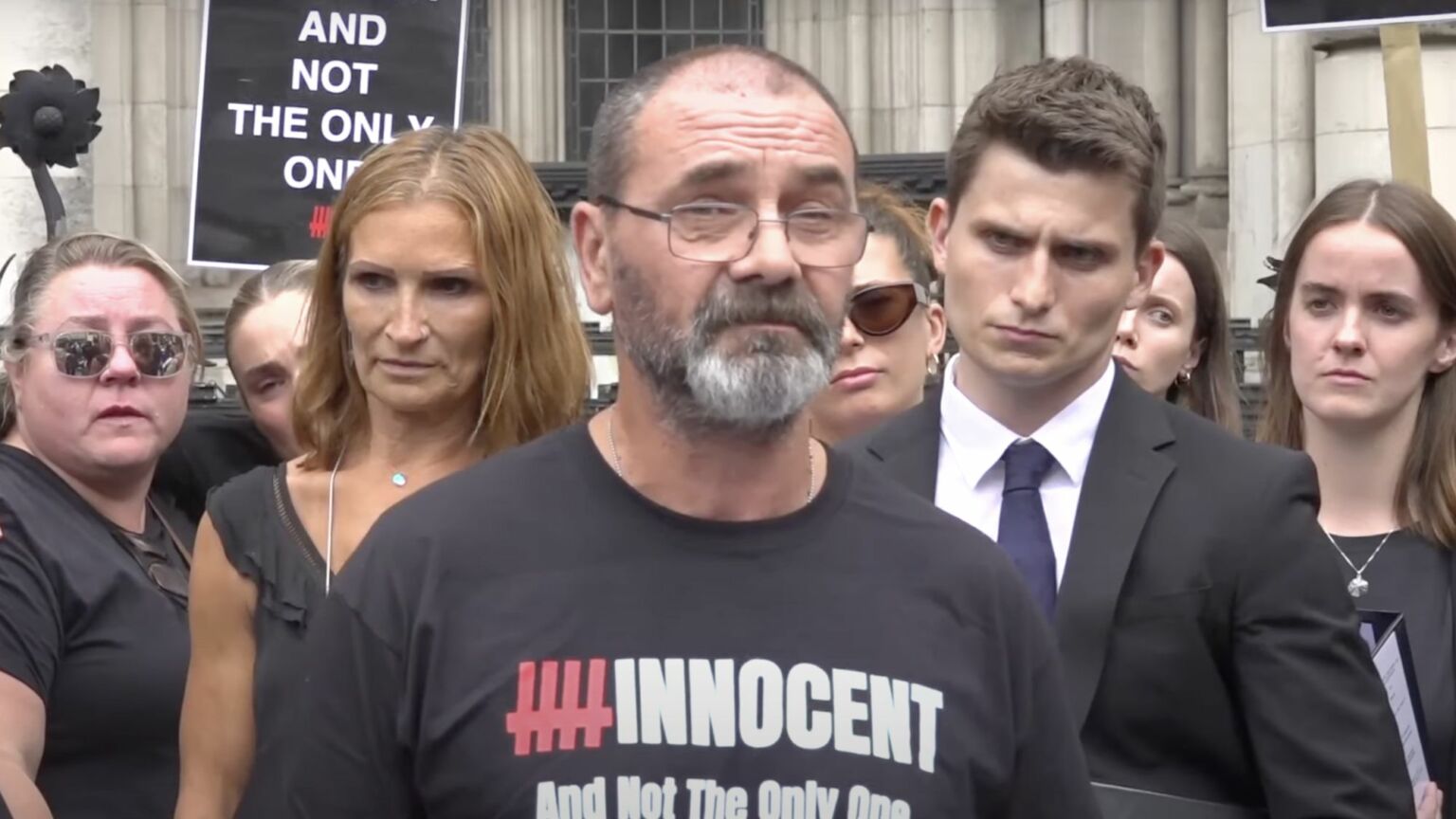

Andrew Malkinson was convicted in 2004 of the violent rape of a woman in Salford, near Manchester, in 2003. In January this year, the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) finally referred his case to the Court of Appeal. In July, after two decades in prison, Malkinson finally had his conviction overturned.

Malkinson’s campaign for justice has been long and tortuous. The grounds for his conviction had always looked shaky. The victim recalled causing a ‘deep scratch’ to her attacker’s face. Yet when Malkinson was visited by the police the day after the attack, he had no such scratch on his face. Nor was there any DNA evidence linking him to the crime. He was arrested and charged after being picked out of a video lineup.

After his conviction, new evidence calling Malkinson’s conviction into question was constantly downplayed by the CCRC. Indeed, the key piece of evidence that eventually led to his conviction being quashed was first identified in 2007. A male DNA profile in a ‘crime specific’ location on the victim’s vest top that did not match Malkinson or the victim’s then boyfriend had been found in a nationwide review of the forensics used in historic rape and murder cases.

The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and Greater Manchester Police were alerted and, in 2009, Malkinson applied to the CCRC to refer his case to the Court of Appeal. Incredibly, the CCRC did not think that the revelations were sufficient to have the case reviewed. One CCRC staff member wrote in a case-log entry: ‘Just because it appears there is someone else’s DNA on the complainant’s vest, not [the boyfriend’s] or the applicant’s, cannot surely produce a successful referral in view of all the other strong ID evidence.’ The CCRC later said in 2011: ‘The location of the DNA on the vest top does not make it any more likely to have been left by the attacker as opposed to a different individual.’

There is little doubt the CCRC failed Malkinson. Established in 1997 with the sole objective of investigating and reversing miscarriages of justice, the CCRC took far too long to do either in Malkinson’s case. Admittedly, it does face two problems. It suffers from a lack of funding and it is also overburdened with applications that have no chance of success. As it stands, anyone with a criminal conviction can apply to the CCRC, and every complaint needs to be investigated to some extent. Applicants do not need legal representation. They can apply while they are still serving their sentence.

This creates a lot of work on cases that may be less deserving of attention than others. And so the CCRC seeks to avoid generating too much work for itself, even if that means failing to follow up on important new evidence and revelations, as it appears to have done with Malkinson.

But this is not just a funding or a work-load problem. The attitude of the CCRC to Malkinson’s case shows a deeper disregard for the presumption of innocence. The dismissive approach of the CCRC caseworkers shows how the possibility that someone may be wrongfully convicted is no longer seen as an egregious wrong. Instead, it is as if the conviction of the innocent is simply an unfortunate part and parcel of the criminal-justice system.

This attitude is reflected in the wider discussion around rape and sexual violence. The police and the CPS have both consistently argued that we need to ‘drive up’ rape convictions. As if the whole objective of the system should be to find defendants guilty, rather than establish the truth in a case. Malkinson’s two decades-long incarceration for a crime he didn’t commit should remind us of the appalling folly of such an approach.

Benjamin Franklin once said that ‘it is better [that] 100 guilty persons should escape, than that one innocent person should suffer’. Today this principle is in danger of being inverted. Many seem to think that it would be better for innocent people to be sent to prison rather than allow conviction rates for certain crimes, especially rape, to remain relatively low. To lock up as many people as possible, whether they’re guilty or not, now seems to be the goal.

Malkinson’s case does reveal the inadequacies of the CCRC. But it also reveals the problem with disregarding the presumption of innocence in favour of ‘believing the victim’ and ‘driving up convictions’. We have allowed one innocent to suffer at the hands of an indifferent criminal-justice system. We should all see that as one too many.

Luke Gittos is a spiked columnist and author. His most recent book is Human Rights – Illusory Freedom: Why We Should Repeal the Human Rights Act, which is published by Zero Books. Order it here.

Michael Shellenberger and Brendan O'Neill – live and in conversation

Tuesday 29 August – 7pm to 8pm BST

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

Picture by: YouTube.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.