Why the AfD is on the rise again

German voters are furious with a tin-eared establishment.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Until last month, few Germans knew anything about the small district of Sonneberg in the eastern state of Thuringia. This changed, however, after the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) won its first ever district-council election there. The AfD candidate – a lawyer called Robert Sesselmann – was elected as Sonneberg’s district administrator, winning 53 per cent of the vote, with the incumbent Christian Democratic Union (CDU) candidate picking up 47 per cent of the vote.

Sesselmann’s victory was even more surprising given that all the other parties – from the Social Democrats (SPD) to the Greens and even the far-left Die Linke – urged their supporters to vote for the centre-right CDU. Indeed, the CDU and the other parties campaigned around one sole objective – keeping the AfD out.

Germany’s political establishment greeted Sesselmann’s victory with shock and borderline hysteria. One SPD politician called it a ‘day of shame’. Others said that a ‘red line’ had been crossed. It didn’t matter that district administrators – Germany has around 300 in total – play a limited, largely managerial role in local politics. For the AfD to hold even the tiniest amount of power clearly terrifies the political class.

A week later, the mood of the political establishment soured further, when the AfD managed to secure its first-ever full-time mayor. Last Sunday, Hannes Loth was elected in the small town of Raguhn-Jeßnitz in the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt. He won with 51 per cent of the vote.

Under normal circumstances, the results of provincial elections wouldn’t cause such a stir. But the AfD’s victories, especially in Sonneberg, reflect its growing popularity across Germany. In fact, the AfD is currently polling nationally at around 19 to 20 per cent, putting it in second place behind the CDU, and ahead of chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats. Its victory in Sonneberg is clear evidence that the political climate is shifting in Germany.

The AfD has always been a problem for the established parties. In the past, they have successfully ‘quarantined’ the AfD, by joining forces against it. But, as Sonneberg shows, this strategy is now failing. For the first time, they seem at a loss with how to deal with the rise of the AfD and with populism more generally.

After Sesselmann’s victory, journalists were sent off to interview the supposedly ‘strange’ people of Sonneberg. They wanted to find out exactly what kind of person would vote for the AfD. What they discovered were people of all ages and walks of life – craftsmen, workers, housewives and many more. ‘The new AfD protest voters are different than expected’, was the title of an NTV report. Indeed, looking at recent studies, it is clear that AfD voters are not all old, unemployed or angry, as they are often portrayed. According to a recent survey, 21 per cent of 30- to 44-year-olds say that they would vote for the AfD. More importantly, AfD voters all tend to have a clear idea of the things they are opposed to – namely, the government’s policies on immigration, energy, climate and the economy.

The establishment has always felt entitled to look down on AfD voters, mocking them as lunatics, racists or simpletons. The elites have long maintained that no respectable person would ever vote for this ‘far right’ party. But this strategy of demonisation is no longer working. Germans are beginning to feel at ease giving their vote to the AfD.

Sonneberg encapsulates this changing attitude. Here, the AfD triumphed, even though the Thuringia branch of the party is especially right-wing. It is headed by the notoriously far-right Björn Höcke, who has been accused of downplaying the Holocaust and, in 2022, was one of the most unpopular politicians in Thuringia. Yet such is voters’ disillusionment with the main parties that even the unsavoury Höcke cannot deter them from voting for the AfD.

Important elections are coming up next year in Thuringia and in other east-German states. And the AfD’s opponents are now starting to sound desperate. ‘Unless there is a dramatic change in mood, next year’s state and local elections could be a triumph for the AfD’, warned Dresden-based political scientist Hans Vorländer after the Sonneberg vote. ‘It is becoming more and more difficult to do politics against the AfD or to win elections against the AfD’, he said.

There is something the main parties could do to ‘win elections against the AfD’ – they could start addressing voters’ concerns. But they’re not interested in doing that. Instead, Germany’s political and media classes are blaming the voters for making the wrong choices and holding the wrong views. Just look at interior minister Nancy Faeser’s response to the Sonneberg election. She has warned against pandering to any of the positions of the AfD. In a recent press conference, she even suggested the idea of banning the AfD altogether.

Demonising the AfD won’t work. Its success rests on voters’ growing opposition to the worldview of the established parties. Many ordinary Germans are now rejecting their pursuit of Net Zero, the absence of border controls and the embrace of gender-identity politics. Refusing to ‘pander’ to those concerns won’t make them go away. If Germany’s political class doesn’t start listening and responding, the popularity of the AfD and other populist movements will only grow. And there will be many more Sonnebergs to come.

Sabine Beppler-Spahl is spiked’s Germany correspondent.

Picture by: Getty.

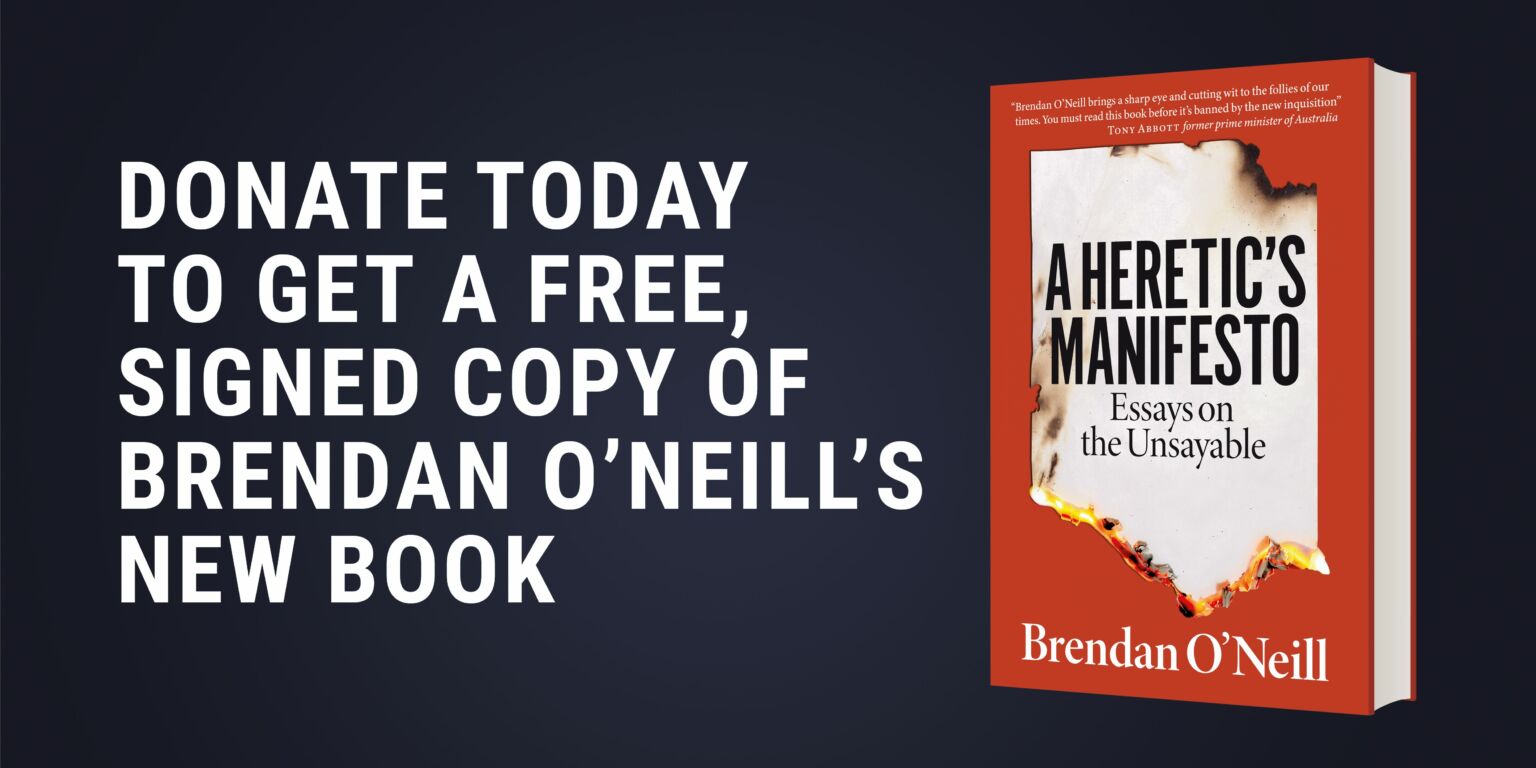

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.