Long-read

The problem with AI apocalypticism

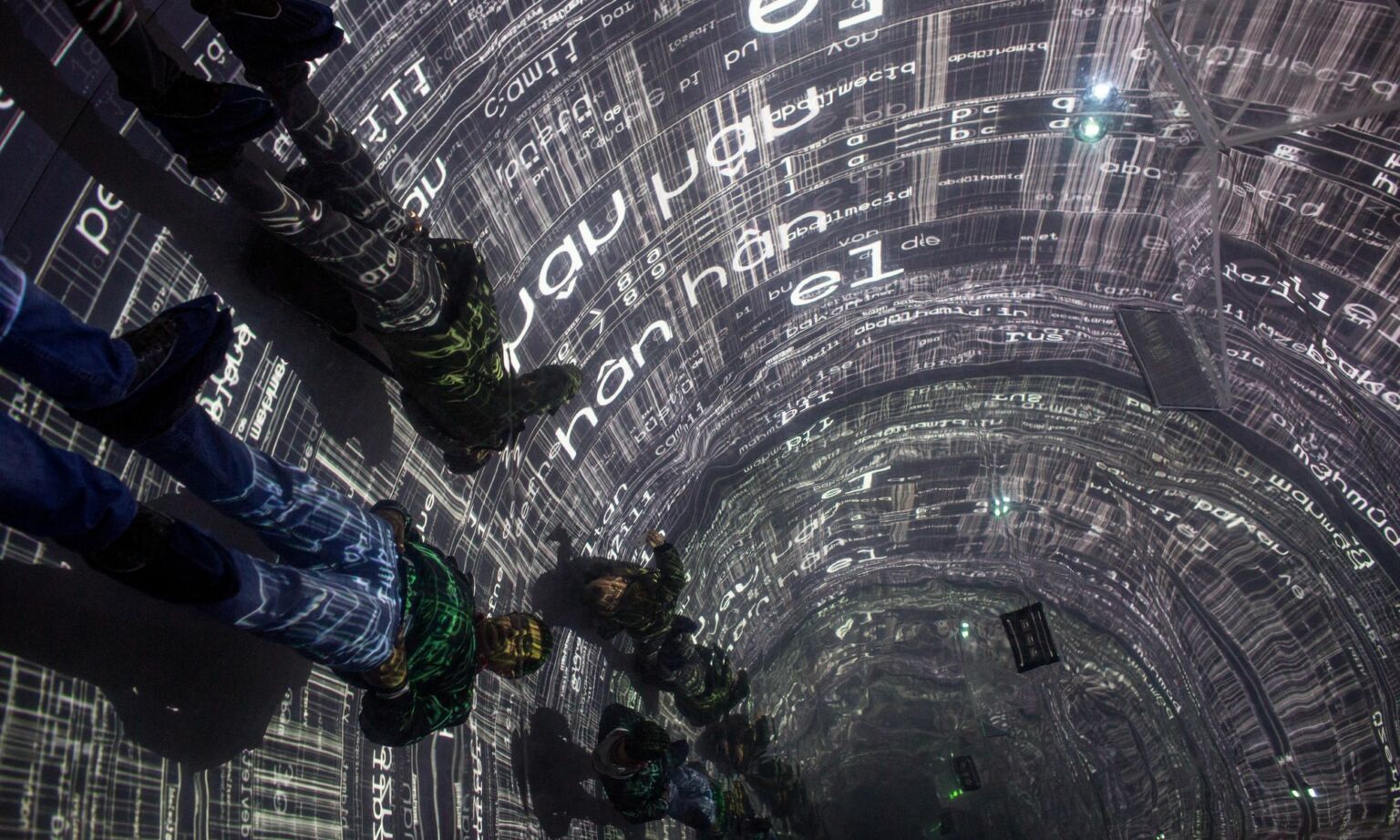

The elites’ fear of artificial intelligence betrays a degraded view of humanity.

Artificial intelligence (AI) was once a discrete topic earnestly discussed among a narrow band of computer scientists. But no more. Now it’s the subject of near daily public debate and a whole heap of doom-mongering.

Just this week, the Centre for AI Safety, a San Francisco-based NGO, published a statement on its webpage asserting that: ‘Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority, alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.’ This apocalyptic statement has been supported by some of the biggest names working in AI, including Sam Altman, the chief executive of OpenAI (the firm behind ChatGPT), and Demis Hassabis, chief executive of Google DeepMind.

There’s no doubt that AI is a major technological breakthrough that really could have a significant impact on our lives. But the predominant narrative that is emerging around AI goes much further than that. It massively overestimates its current potential and invariably draws absurdly dystopian conclusions. As a result, non-conscious AI assistants, from ChatGPT to Google Bard, are now regarded as potentially capable of sentience and of developing an intelligence far superior to our own. They are supposedly just a short step from developing independent agency, and of exercising their own judgement and will.

Some AI enthusiasts have allowed themselves to indulge in utopian flights of fancy. They claim that AI could be about to cure cancer or solve climate change. But many more, as the Centre for AI Safety statement attests, have started to speculate about its catastrophic potential. They claim that AI will turn on us, its creators, and become a real and mortal threat to the future of human civilisation.

By believing that AI will develop its own sense of agency, these AI experts, alongside assorted pundits and politicians, are indulging in an extreme form of technological determinism. That is, they assume that technological development alone determines the development of society.

The technological determinists have got things the wrong way around. Their narrative ignores the way in which society can mediate and determine technological development. Those technologies that have flourished and changed society have only done so because human beings have adopted them and then adapted them to their needs. In turn, those technologies, no matter how rudimentary, have allowed humans not only to meet our needs but to cultivate new needs, too. As Karl Marx wrote of the need to eat: ‘Hunger is hunger; but the hunger that is satisfied by cooked meat eaten with a knife and fork differs from hunger that devours raw meat with the help of hands, nails and teeth.’

The technologically determinist narrative that has developed around AI doesn’t just ignore the way in which human society mediates technological development. It also assumes that humans are utterly powerless before the might of emerging technologies. The AI fearmongers seem to think that human subjectivity no longer exists.

The apocalyptic AI narrative has emerged with incredible speed. At the end of March, 50 generative AI scientists, including key figures like Twitter CEO Elon Musk, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak and researchers at AI company DeepMind, issued a public letter through the Future of Life Institute. They called for a temporary halt in the training of AI systems, warning that we risk developing and deploying ‘ever more powerful digital minds that no one – not even their creators – can understand, predict or reliably control’. As far as they are concerned, we’re in danger of creating superintelligent AI that could potentially pose an existential threat to humanity.

Their call for something to be done picked up momentum in early May when Altman, alongside the CEOs of Microsoft, Alphabet (Google’s holding company) and Anthropic, met at the White House to discuss the threats posed by AI with senior US officials. Then Altman appeared before the US Senate on 16 May, demanding that AI be regulated. And so the doomsday narrative was set.

As ever, it is the European Union that has led the rush to regulate. Its Artificial Intelligence Bill, initially proposed in April 2021, has already passed its first parliamentary hearing. This law will likely set the bar for other legislatures to meet, as the UK and US consider how best to regulate AI.

This mass of prospective AI legislation, fuelled by an increasingly apocalyptic and fatalist narrative, reinforces the sense that there really is something to fear – that something must be done to stop AI before it’s too late.

One of the most significant interventions in this increasingly febrile debate came from the so-called Godfather of AI, Geoffrey Hinton. At the beginning of May, he resigned from Google, claiming that he now regrets his contribution to the development of AI.

Hinton won the equivalent of a Nobel Prize in computer science in 2018 for his work on AI neural networks. And yet there he was last month telling several news outlets that large technology companies were moving too fast on deploying AI to the public. He claimed that AI was achieving human-like capabilities more quickly than experts had forecast. ‘That’s scary’, he told the New York Times. What truly shook him was ‘the realisation that biological intelligence and digital intelligence are very different, and digital intelligence is probably much better’. Elsewhere, he told the Financial Times that ‘it’s quite conceivable that humanity is a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence’. And just in case we hadn’t got the point, he asked readers to imagine ‘something that is more intelligent than us by the same degree that we are more intelligent than a frog’. Scary stuff, indeed.

Hinton is overreaching here. It is a huge leap from developing algorithms that attempt to emulate the human brain to developing ‘digital intelligence’ that surpasses ‘biological intelligence’. He may well be a genius when it comes to developing artificial intelligence, but he is peddling absolute nonsense about human intelligence.

Sadly, claims from Hinton and others are being repeated as the uncontested truth. Historian, philosopher and best-selling author Yuval Noah Harari now claims that generative AI, like ChatGPT, has ‘hacked the operating system of our civilisation’. ‘When AI hacks language’, he warns, ‘it could destroy our ability to have meaningful conversations, thereby destroying democracy’. Anti-globalisation activist Naomi Klein fears that the wealthiest companies in history are seizing the sum total of human knowledge and walling it off behind proprietary products. Meanwhile, MIT economist Daron Acemoglu claims that AI will ‘damage political discourse, democracy’s most fundamental lifeblood’.

Amid so much pessimism from experts and commentators, who wouldn’t be concerned about AI? If a significant segment of our elites are to be believed, we are on the cusp of a Terminator-like world, where a sentient AI is about to oppress and even erase humanity.

It is worth asking why such intelligent people can only imagine the worst when it comes to this remarkable technology. Why would a superhuman intelligence, if that indeed is what is being created, seek to destroy us? Wouldn’t an AI system aim to surpass, rather than destroy, the achievements of human civilisation?

This fatalistic, dystopian view of AI has little to do with the technology itself. It comes from our elites’ diminished view of human agency. From their perspective, machines are agents, while humans are passive objects. This reflects a very 21st-century malaise, in which humans are thought to be subject to forces entirely beyond our control.

Dystopian visions involving anti-human robots are nothing new. Czech writer Karel Čapek’s 1920 play, RUR: Rossum’s Universal Robots, first introduced the word ‘robot’ to the world. It told the story of artificial humans (robots) revolting against their human creators, leading to the extinction of humanity. Fritz Lang’s remarkable piece of expressionist sci-fi, Metropolis, released in 1927, also presents a future in which robots tyrannise humans, manipulating people and maintaining control over a highly stratified society. Then there is Isaac Asimov’s ‘robot’ series of novels, beginning with I, Robot in 1950, which explored the implications of advanced robotics and the potential for robots to seize control over human society.

All these writers’ dark visions of an inhuman future, governed by a robotic bureaucracy, draw deeply on their experiences of industrial slaughter during the First and Second World Wars and the totalitarianism of fascism and Stalinism. But these writers and their dark visions were exceptions to a more general rule. As dark as their times were, they lived in societies in which people were still expected to take responsibility for the future. There was still a sense that people could harness technological advances to forge a better world.

Indeed, a very different vision for the future can be found in Vasily Grossman’s magisterial 1959 novel, Life and Fate. It was written from the trenches of the Russian front during the Second World War, one of the most barbaric chapters in human history. But, in the book, Grossman’s faith in humanity and technology persists. He is still able to dream of a future in which an ‘electronic machine’ can ‘solve mathematical problems more quickly than man, and its memory is faultless’. Grossman’s imagined machine of the future ‘will be able to listen to music and appreciate art; it will even be able to compose melodies, paint pictures and write poems’. It will surpass the achievements of man, he says.

The contrast with today is remarkable. Even in the aftermath of the barbarism of the Second World War, Grossman sees what we call AI today as something that would elevate humanity, not threaten it – that would carry forth the best of man, composing, painting and writing. His ‘electronic machine’ embodies what he terms the ‘peculiarities of mind and soul of an average, inconspicuous human being’. Grossman’s machine embodies and advances humanity. It will recall, he writes:

‘Childhood memories… tears of happiness… the bitterness of parting… love of freedom… feelings of pity for a sick puppy… nervousness… a mother’s tenderness… thoughts of death… sadness… friendship… love of the weak… sudden hope… a fortunate guess… melancholy… unreasoning joy… sudden embarrassment…’

Grossman’s AI does not seek to destroy or punish humanity. Instead, it expresses the human condition. His AI is born of a humanist vision. Machines, he thought, could enable humanity to elevate itself and go beyond its previous limits.

Compare that with the miserable vision of experts today. They envisage AI as a deeply inhuman force that will almost inevitably turn against us, degrade us and punish us. It won’t embody the best of us. It will embody the worst of us.

Moreover, the very fact that they see AI tools like ChatGPT as a massive step towards sentient intelligence shows how little they think of sentient intelligence. It took over 175 billion parameters of data, 285,000 processor cores and 10,000 graphics cards to develop ChatGPT-3. That’s roughly equal to the computing power of the 20 most powerful supercomputers in the world combined. And the end result is an machine that can only regurgitate language without understanding a single word. What ChatGPT does is impressive in its own terms. But, as it stands, it is not a patch on human intelligence.

Grossman’s machine would require so much more computer-processing power and energy than we can currently produce. And it would require a far more advanced society to realise it – a society in which the energy crisis would be a distant memory and quantum computing an everyday reality. It is unlikely that a society this advanced would be concerned about a chat bot plotting against us.

In their efforts to constrain and legislate against this emergent technology, today’s AI experts and their cheerleaders in the media are doing humanity a huge disservice. Their dark vision of AI reflects their lack of belief in humanity, their sense that we are at the mercy of forces beyond our control. And, as a result, they are shackling us to a culture of low expectations.

Hannah Arendt can help shed some light on our current impasse. In her masterpiece, The Human Condition (1958), she criticised modern theories of behaviourism. These theories conceive of human behaviour as either a reflex to certain environmental stimuli or as a consequence of an individual’s history. Arendt claimed that behaviourism reduces complex human experiences and actions to simplistic cause-and-effect relationships. And, as a result, they efface humanity’s capacity for spontaneity, creativity and freedom. The problem with behaviourist theories, she writes, ‘is not that they are wrong but that they could become true, that they actually are the best possible conceptualisation of certain obvious trends in modern society’. That is, in the bureaucratic society of Arendt’s lifetime, individual behaviour was increasingly being treated as something that could be managed and directed. Humans were being reduced to objects. She continues: ‘It is quite conceivable that the modern age – which began with such an unprecedented and promising outburst of human activity – may end in the deadliest, most sterile passivity history has ever known.’

Arendt’s words could have been written with the AI doomsday narrative in mind. In an era in which humans are viewed as the objects of inhuman forces, from climate change to pandemics, unleashed by our own actions, is it any wonder that AI is presented as a threat? The AI doomsday narrative is, as Arendt has it, the ‘conceptualisation of certain obvious trends in modern society’.

And so something as potentially useful as AI has become a means for politicians and experts to express their fatalistic worldview. It is a self-fulfilling tragedy. AI could enable society to go beyond its perceived limits. Yet our expert doomsayers seem intent on keeping us within those limits.

The good news is that none of this is inevitable. We can retain a belief in human potential. We can resist the narrative that portrays us as objects, living at the mercy of the things we have created. And if we do so, it is conceivable that we may, one day, develop machines that can represent the ‘peculiarities of mind and soul of an average, inconspicuous human being’, as Vasily Grossman put it. Now that would be a future worth fighting for.

Dr Norman Lewis is managing director of Futures Diagnosis and a visiting research fellow of MCC Brussels.

A Heretic’s Manifesto – book launch

Monday 5 June – 7pm to 8pm

Andrew Doyle interviews Brendan O’Neill about his new book. Free for spiked supporters.

Pictures by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.