The mindless absurdity of hate-speech laws

Ireland's plan to criminalise 'hatred' is a sinister attempt to control thought.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hatred and Hate Offences) Bill is working its way through the Irish parliament. It now seems inevitable that Ireland will become the latest country to make so-called hate speech a crime. Almost 40 other nations have already enacted similar laws curbing freedom of expression.

There are many good reasons why hate-speech laws are bad. Those have been eloquently expressed, on spiked and elsewhere – not that it looks like anyone in power is listening. But for me, the most depressing aspect of hate-speech legislation is how absurd it all is. There’s a stupidity, illogicality and childishness at the core of the argument for hate-speech laws.

After all, what even is ‘hate speech’? Yes, it’s defined in legislation under certain parameters – the ‘communication’ of material or speech that might ‘incite hatred’ against people with certain protected characteristics (such as race, religion and gender). But when applied in the real world – what speech exactly is deemed to incite hatred? – it all becomes so vague. And a vague law is by definition a bad law.

Essentially, anything said by anyone, under any circumstances, regardless of their intentions or indeed their true feelings, can be construed as hate speech – if someone reacts to it as such. An individual’s speech becomes hate speech, punishable to the full extent of the law, if someone else perceives it to have been hateful towards people with protected characteristics. Well, that’s bound to work out well.

The concept of hate speech is riddled with contradictions. It seems you can express hatred for an entire group of people, provided it’s not a group with ‘protected’ characteristics. So you can say, ‘I hate telemarketers. All of them.’ Yet, despite it being a clear expression of hatred towards a particular group, it is not legally defined as hate speech. You can also say ‘I genuinely hate Keir Starmer’. It’s a sincere admission of hatred. But because Keir Starmer is a person, not a protected group, it doesn’t count.

The idea of hate speech raises so many more questions. Can an Irish person say they hate all British people? Is that okay, as a kind of freedom-of-expression payback for colonisation and the Famine? Can a British person respond in kind? After all, some of us bombed some of your cities in recent memory.

And can someone use the sincerity defence? Can a person say, ‘I can’t help my feelings. I genuinely hate such-and-such. I don’t wish any ill on them and will never do anything to hurt them, but that’s what’s in my heart’? After all, if we are criminalising hatred, aren’t we criminalising an emotion, a feeling? Indeed, aren’t we criminalising thoughts, even if they’re subconscious, so you don’t even know that you have them? In short, hate speech could make the contents of your soul illegal.

Incidentally, is there an age cut-off point? A kid can be charged with assault or robbery. Can they also be done for saying something stupid on the internet?

Then there’s the sarcasm problem. What if I write, ‘I absolutely do not hate politicians and definitely don’t want them to be shot into space. In fact I love all of them. And I am not, repeat not, being ironic.’ Is this hateful? Or does it slip through the irony loophole?

Some of the above questions are clearly tongue-in-cheek. But the regulation of speech is becoming so ridiculous that it’s entirely plausible they will soon need to be asked.

Above all, hate-speech legislation is being enacted to control how the people think. Humpty Dumpty says in Alice in Wonderland: ‘When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.’ The Humpty Numpties who now run the world have modified that: ‘When you use a word, lowly prole, it means just what I choose it to mean. And I’ve got the law on my side.’

Eighth-century English scholar Alcuin is credited with first declaring, Vox Populi, Vox Dei – the voice of the people is the voice of God. I don’t believe in God, but I do believe that the voice of the people is sacred. It’s time we stood up to those trying to regulate and silence it.

Darragh McManus is an author and journalist. Visit his website here

Picture by: Getty.

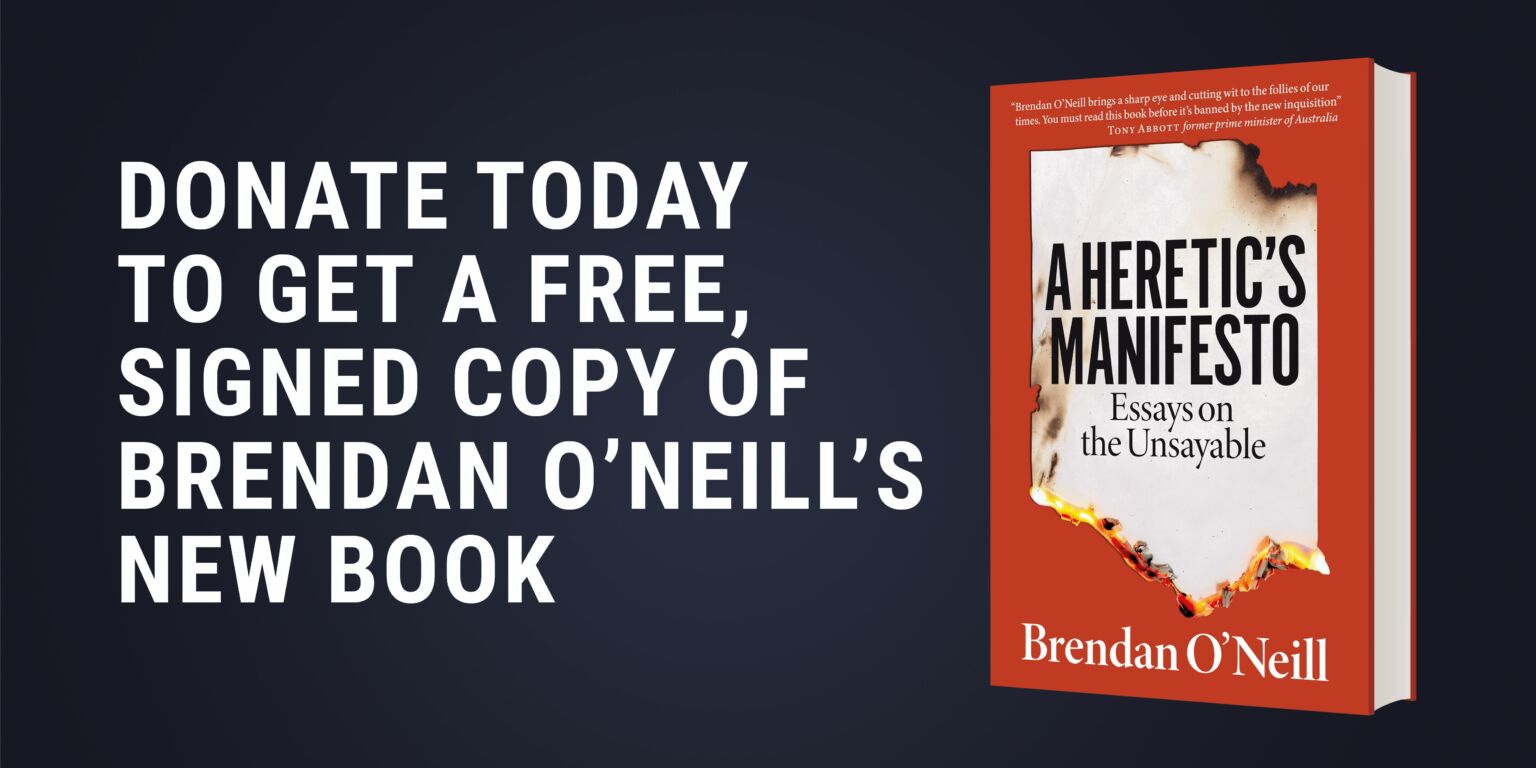

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.