We must not censor art due to the crimes of the artist

Eric Gill’s crimes were reprehensible, but the removal of his work from display is illiberal and wrong.

Donate to spiked this Christmas, and help keep us free, fearless and independent.

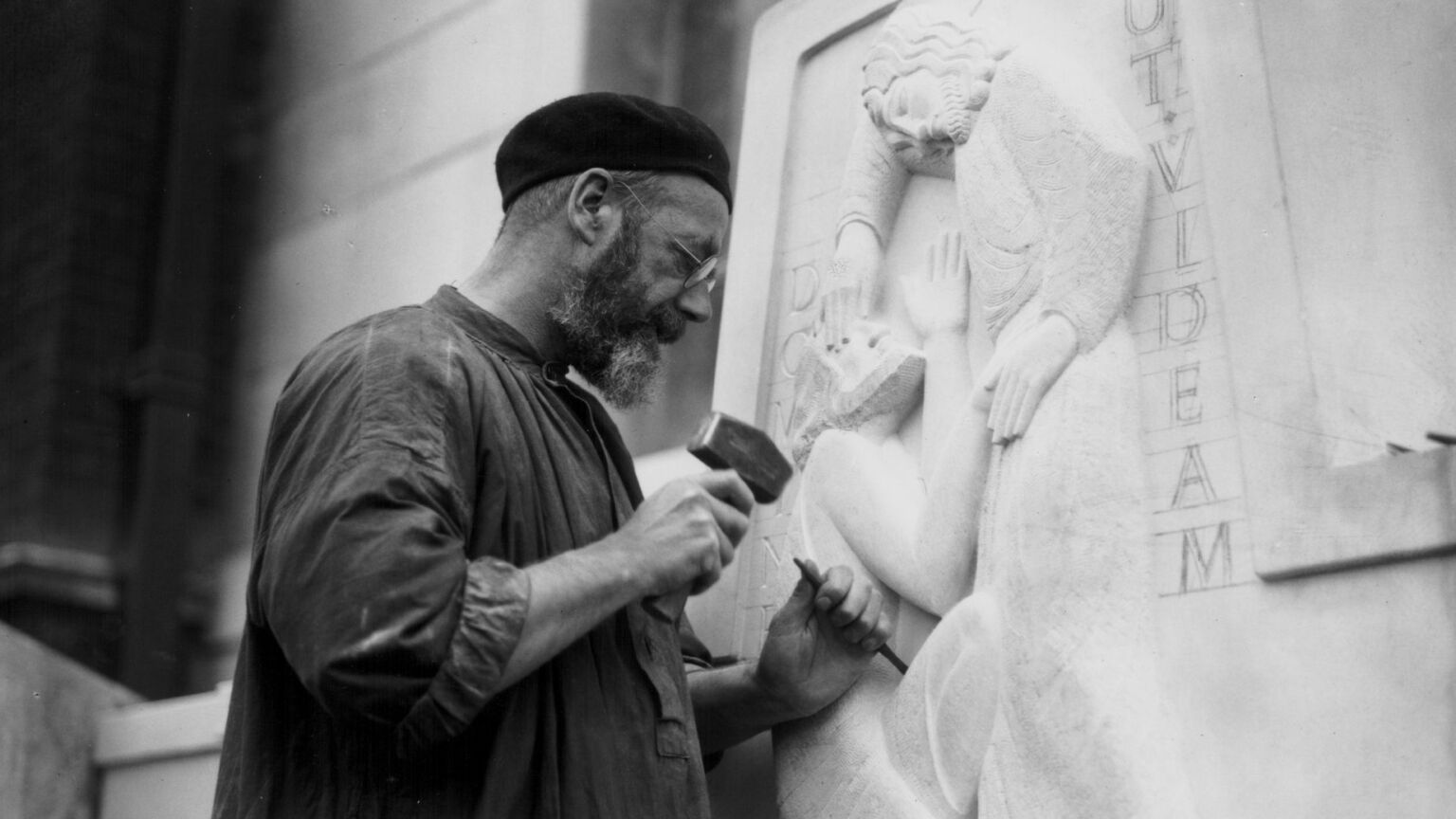

The art of Eric Gill (1882-1940) is under attack – not by a vandal this time, but by the museum that should be preserving his work. The Guardian reported last week that Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft has decided not to re-open a gallery dedicated to Gill’s work, due the sexual abuse the artist subjected his daughters and younger sister to. Gill’s crimes have tarnished the artist’s reputation since the late 1980s, when details from his diary were published in a posthumous biography and confirmed by family members.

Much of the museum’s collection of Gill’s art was produced by the artist when he lived in Ditchling, the East Sussex village where the gallery is located, between the 1910s and 1920s. The collection is central to the museum’s reputation and popularity. When, in 2012, the museum received a £2.3million grant to expand from the Heritage Lottery Fund, it was partly based upon its Gill collection. Gill was famous for his carved stone statues and woodcut prints, many with erotic or religious subjects. He was also famed for his innovative typeface designs, which were modern versions of traditional styles. Now the museum says that Gill’s art will only be shown when it is ‘central’ to an exhibition theme. Will the museum be returning any of its grant?

This is not the first time that Gill’s art has come under attack. In January, a man attacked Gill’s statue of Prospero and Ariel (1931-32), carved for the façade of BBC Broadcasting House in central London. The vandal said he was protesting against paedophilia and the BBC’s role in concealing information about Jimmy Savile’s sex crimes against children.

That incident came just days after the ‘Colston Four’ were acquitted. The group managed to topple the statue of 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston during a Black Lives Matter protest in Bristol in 2020. Their acquittal gave rise to concerns that iconoclasm would be overlooked if the outrage of attackers was deemed morally just. Police stood by and let protesters tear Colston’s statue down, and the courts later condoned it. Perhaps the Gill vandal felt emboldened to try something similar. The destruction of historic art (and public property) had been officially legitimised.

Unlike that previous attack on Gill’s art, the suppression of his works at the Ditchling museum has been more covert in nature – and that makes it all the more troubling. Without public consultation or announcement, the museum decided to withdraw access to Gill’s art, despite it being essential to the canon of British modernism. You do not have to condone Gill’s crimes to recognise the undeniable influence of his artistic style. His typefaces are still in use today – just check your Microsoft Word fonts.

How far along this line will museums go? If art should be removed on the basis of apparent crimes, then will we have to remove paintings by Caravaggio, who killed a man, or those by wife-beater Pablo Picasso? This was the premise of Channel 4’s recent show, Jimmy Carr Destroys Art, which purchased works by controversial artists only to have a studio audience vote on which should be dramatically destroyed.

This logic could spread further. How long before an artist will be suppressed on grounds of other, less clearly criminal, failings? Does the treatment of Gill and other controversial artists provide activist curators with carte blanche to censor indiscriminately?

Until very recently, we had lived in something of a historical blip, in which morality and art were considered separate. For the majority of history, this view was considered strange. One of the gains of liberalism was viewing art as separate from morality; for the ancients, art was supposed to declare the soul of the artist. One of the characteristics of modern art was the way its makers attempted to step aside from traditional morality.

One cannot claim to be a cultural liberal and apply moral censure to art on the basis that the artist’s character pollutes his work. We need to step back from censorship and allow viewers to make their own judgements, assessing art on its own merits rather than those of its creator. This stealth-cancelling of art, as we have seen in Ditchling, is neither brave nor moral.

Alexander Adams is an artist, art critic and author. His books Culture War and Iconoclasm are published by Societas.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.