The Nineties: our last decade of freedom?

Dylan Jones’s Faster Than a Cannonball captures the exuberance and spirit of the Nineties.

There is a telling moment in former GQ editor Dylan Jones’s insider account of the 1990s, Faster Than a Cannonball: 1995 and All That. Loaded journalist Martin Deeson has gatecrashed a Cannes Film Festival party with his photographer in tow. ‘I ordered a large scotch, two gin and tonics, two glasses of champagne and then asked Derek what he wanted’, recalls Deeson. The two journalists then staggered around rat-arsed chatting to various A-listers before bumping into Sixties style icon Terence Stamp: ‘After looking at me for a while Stamp said, “I just don’t think I want to talk to you”, and walked away.’

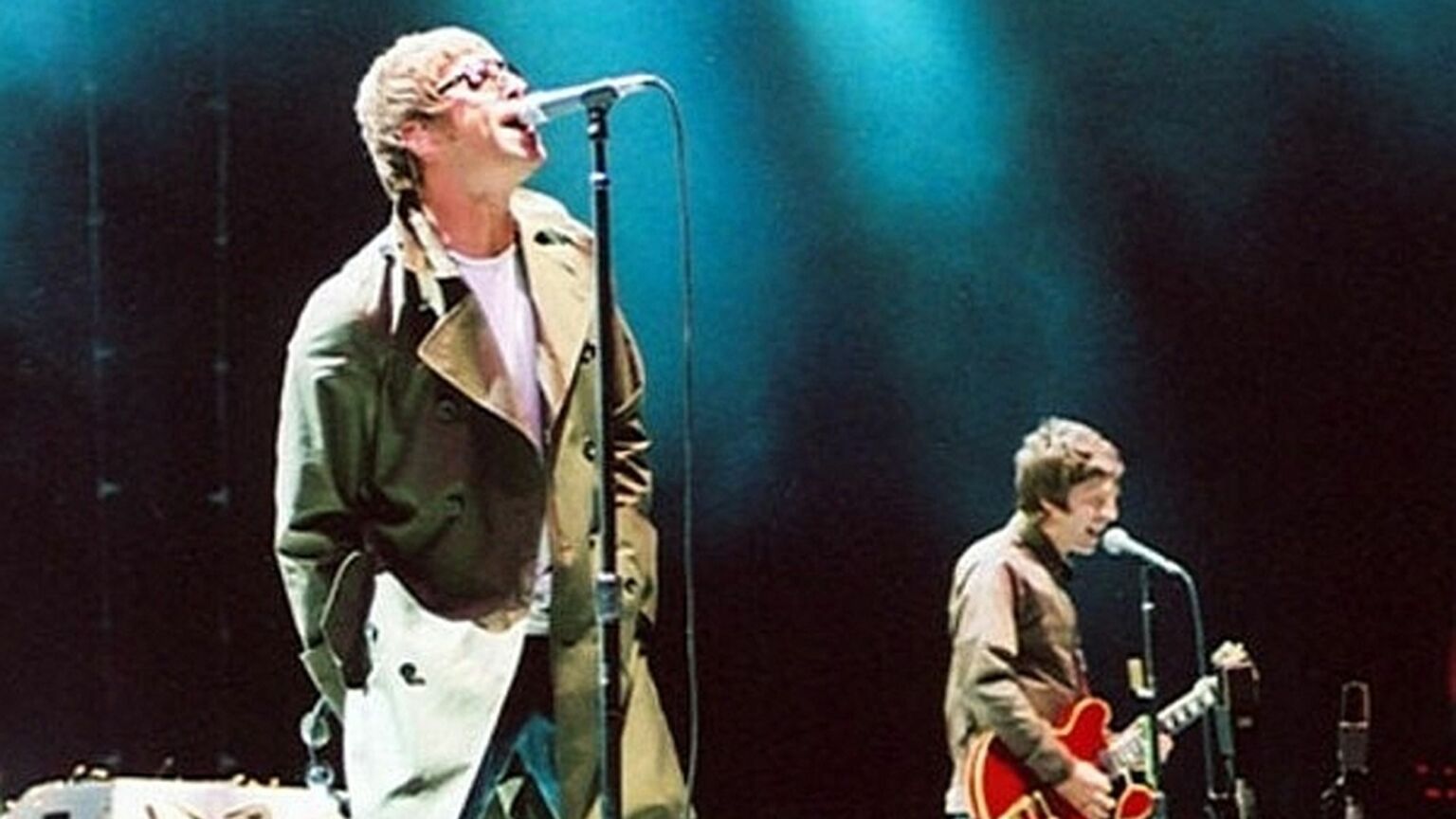

Stamp’s dismissive reaction speaks volumes. It shows up the Nineties as the noisier, embarrassing and somewhat envious younger brother of the Sixties. The culture of the Nineties, writes Jones, betrayed a ‘deep and profound melancholic longing for the Sixties’. This was evident in everything from Oasis’s pastiche of the Beatles to the ‘Swinging London’ shtick of 1997’s Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery. As Blur’s Alex James puts it, by then ‘the decade was already lampooning itself as a kind of shit Sixties’.

Faster Than a Cannonball: 1995 and All That interweaves interviews with the era’s main protagonists with Jones’s own cultural reflections and judgements. He presents 1995 as the apex of the Nineties as a cultural moment, peaking with the Oasis vs Blur chart battle, the rise of the Young British Artists (YBAs) and the success of Loaded magazine (which by then was selling half-a-million copies monthly).

Jones offers a month-by-month account of 1995, beginning with Suede’s reluctant role as the harbingers of Britpop in January, to the release of The Beatles Anthology in December. Jones captures the creative exuberance of the period, while acknowledging the knowingness that hampered it. It was a decade that was never quite able to escape the shadow of Swinging London, let go and enjoy itself.

This might explain why Faster Than a Cannonball’s best chapters cover the movements that were radically of their time. February’s account of the rise of the Young British Artists (YBAs) draws not just on interviews with the artists themselves, but also from their early patron, Doris Lockhart, and their founding father, Goldsmiths artist-in-residence Michael Craig-Martin. Craig-Martin not only nurtured the YBAs’ talent, but also taught ‘things art schools traditionally hadn’t talked about – how to promote yourself, how to get your work out into the world, how to get noticed’.

The hero of the YBAs has to be Tracey Emin, who starts the decade subsisting on potatoes grown on her balcony. By 1995, she is spending her birthday singing karaoke with Neil Tennant of the Pet Shop Boys and Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker. She recalls Cocker singing ‘Common People’, which he did without touching a line of coke, while he admonished those who did.

Jones’s look at the rise of the YBAs sheds light on the wider cultural and economic environment they were able to benefit from and grow up in. As one-time Goldsmiths student Alex James, a contemporary of Damien Hirst, put it: ‘Someone like Damien now, going to art college would be working up 30 grand’s worth of debt. There was so much creativity at the time because there was a financial safety net and… rent was so cheap in London. There was time and space for people to fuck about, and fucking about is where it all starts really.’ Freedom to fuck about in London feels like a luxury few can afford these days.

As Faster Than a Cannonball rolls on through the year, Jones charts all the big events. Labour has its Clause IV moment in April. The August battle for No1 between Oasis’s ‘Roll With It’ and Blur’s ‘Country House’, which felt forced at the time, is treated with reverence – despite both bands freely admitting they were fighting with some of their weakest songs. Jones also provides some gossip. Blur frontman Damon Albarn’s decision to release ‘Country House’ on the same day as ‘Roll With It’, much to his music label’s horror, was due to a fit of competitiveness after discovering he and Liam Gallagher were sleeping with the same girl (surely that’s quite Sixties).

Jones also offers some entertaining musings on 1995’s major characters, from his description of Jarvis Cocker as a ‘brightly dressed Lowry stickman’ to a seven-page digression on Kate Moss’ supergirl-next-door vibe. And then there is Jones’s take on the then 60-year-old interior designer, Nicky Haslam, who spent 1995 trying to emulate a 23-year-old Liam Gallagher. ‘Overnight [Haslam] exchanged his Savile Row bespoke suits for Evisu jeans and camo jackets’, writes Jones. ‘He dyed his hair squid-ink black and had a full face-lift.’

The misbehaviour of the Nineties’ glitterati documented here does raise a question: why did they leave such a boring wasteland behind them? London in the Nineties may have been ‘sex in the toilets, loads of coke, lap dancing, the lot’, as socialite Fran Cutler recalls. But since then it’s been smoking bans, thoughtpolicing and yoga. They helped create an environment in which, as Noel Gallagher himself notes, ‘You can’t say or be or do, or suggest or take the piss out of or be irreverent about anything or any fucking section of society’.

That libertine spirit of the Nineties is so missing today.

Henry Williams is a writer based in London.

Faster Than a Cannonball: 1995 and All That, by Dylan Jones, is published by White Rabbit. Order it here.

Picture by Will Fresch, published under a creative-commons licence.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.