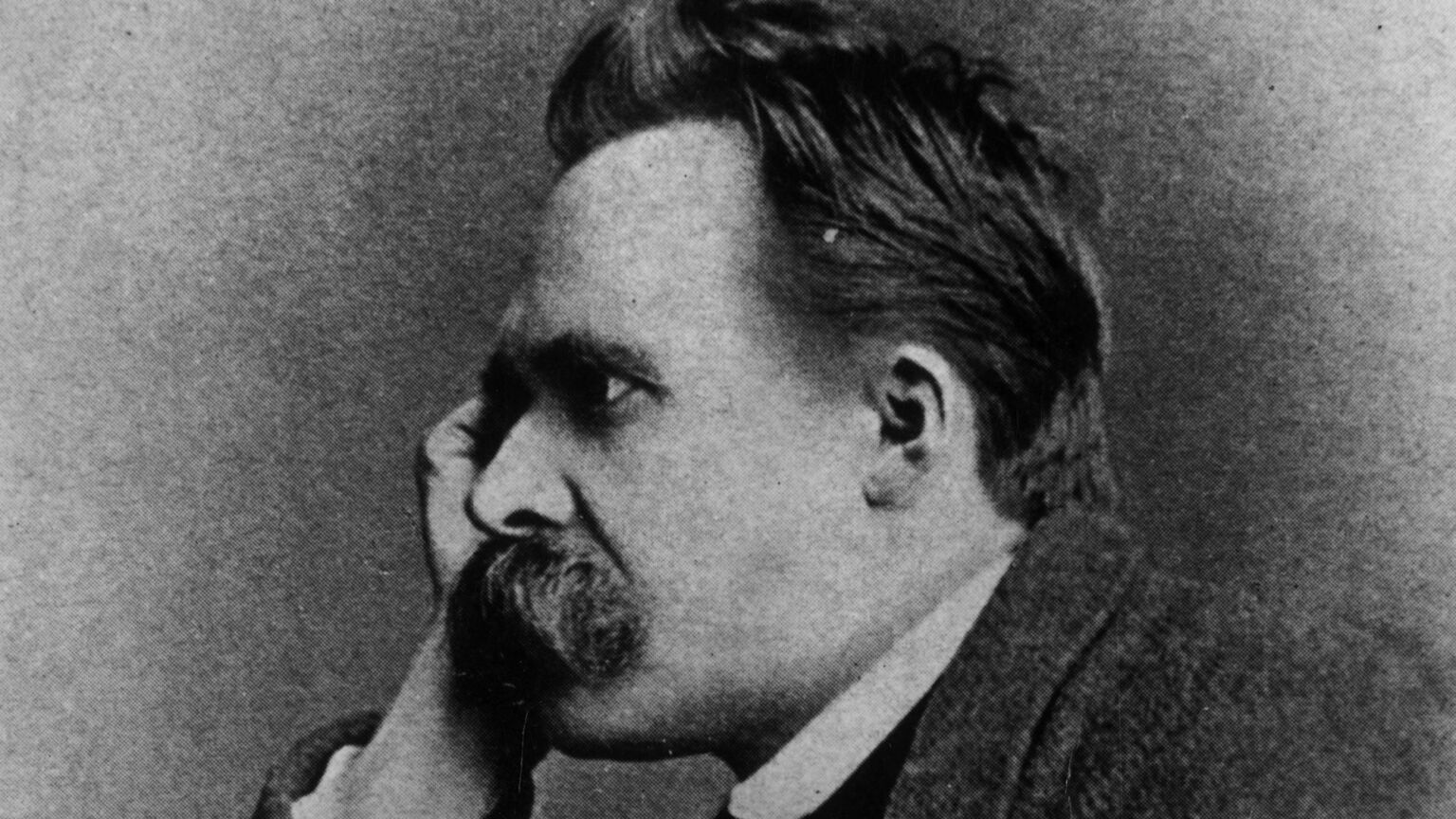

The twilight of Nietzsche

Lesley Chamberlain's Nietzsche in Turin captures the agony of the philosopher’s last year of sanity.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

For years, Friedrich Nietzsche wasn’t taken seriously as a philosopher. Indeed, many didn’t regard him as a philosopher at all. He was instead dismissed as a clever provocateur – a witty aphorist who composed eccentric books replete with pithy observations and vertiginous tirades. He mixed ecstatic tones with convulsive invective, all collected under arresting titles such as Beyond Good and Evil, Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist.

Unlike conventional philosophers, Nietzsche had no unified, coherent theory. He didn’t proceed in a methodical, calm manner, advancing to a carefully delineated conclusion. He never encumbered his prose with technical expressions, jargon or cloudy terminology. No plodding Kant or Hegel was he. He was a mystic and a seer, advocate of the Übermensch, the ‘will to power’, ‘eternal recurrence’ and the Antichrist.

Nietzsche was also as much a psychologist as a philosopher. His central concern was that life involved struggle and self-overcoming. He said that the only authority we can appeal to in our embrace of strife is ourselves. ‘May each man, or woman, be only his or her true disciple’, he wrote in a letter in 1878. Or as he once put it more pithily: ‘Live dangerously!’ Why? Because, as he famously wrote in 1888: ‘That which doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.’

To the acolytes Nietzsche began to attract in the 1890s, he was a prophet. By this time, he had become insane, following a mental collapse in Turin in January 1889. In his followers’ eyes, it was precisely this madness that afforded him mystical status. It was held up as proof that he had perceived the hideous reality of mankind’s bleak fate, now that he had killed God. As Nietzsche himself had put it: ‘If you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back at you.’ Never mind that his madness may have had a more prosaic origin in syphilis.

The last full year of Nietzsche’s sanity was 1888. This is the focus for Lesley Chamberlain’s study, Nietzsche in Turin. First published in 1997, it has now been re-issued in honour of its 25th anniversary. Although it is ostensibly set in one specific time and place, the work shuttles back and forth throughout Nietzsche’s life and ideas. It’s a primer masquerading as a snapshot.

And what a tragic year 1888 was for Nietzsche. Not only was he on the precipice, with his mind starting to unravel in October, but he was also finally beginning to attain the recognition he had so desperately yearned for. Since his books first began appearing in earnest in 1878, they had either been scorned or ignored. Ten years later, just as he was about to enter the darkness, his thoughts were finally starting to see the light.

It would be easy to present Nietzsche’s final sane year in sickly, sentimental or sensationalist terms. But Chamberlain lets the events speak for themselves. We are presented from the outset with an all-too-human character – a struggling independent writer, forever on the move between Switzerland, France and Italy. Nietzsche was hugely industrious in transforming his manifold thoughts into words, but was forever failing to find an audience. We read tantalising correspondence, chiefly from Denmark, where lectures on his work in Copenhagen attracted full houses. This was evidence that the tide was turning. But it was all too late.

Nietzsche the writer and Nietzsche the person were often two different beasts, and could be seen in contrast or as complementary. For such an abrasive and belligerent writer, who glorified power, extolled the hypothetical Übermensch and disdained the weak, he was himself a feeble character, a martyr to crippling headaches and acute myopia, which prevented him from writing for long periods at a time. That, incidentally, explains his predilection for a brief and aphoristic style.

Nietzsche’s outpourings doubled up as a form of catharsis and wish-fulfilment. As Chamberlain writes: ‘The combined pressures of sickness, penury and obscurity go part way to explain the frequency of such terms as power (Macht) and strength (Kraft), sickness (Krankheit), rottenness (Verdorbenheit, Verderbnis) and decay (décadence, Dekadenz) in his writing.’ That Chamberlain is a fluent German speaker adds much weight to this book. Many of the abstract nouns Nietzsche used demand not just translation, but elucidation. Meanwhile, his penchant for puns and wordplay are lost in English translation. Chamberlain also knows her Richard Wagner, which is essential to understanding Nietzsche and his ambivalent relationship with that man and his music.

To regard Nietzsche as a self-help author, writing primarily for himself, helps to put his least convincing idea – eternal recurrence – into perspective. This is the idea that we will live our lives again and again, ad infinitum. For an anti-metaphysician who suggested that we can strive to be higher, better beings, this fatalistic notion of eternal recurrence seems jarring. He devised it in 1881, at a time of personal crisis and romantic rejection, and one must conclude that it was a consolatory comfort blanket. It could be put more prosaically thus: shit happens.

Then there is the other contrast between the thunderous, apocalyptic philosopher who proclaimed ‘I am dynamite’ and exhorted us to ‘philosophise with a hammer’, and the diminutive, polite, softly spoken man with a high-pitched voice. As Resa von Schirnhofer, a young philosophy student with whom Nietzsche had climbed mountains behind Nice, remembered: ‘So unrestrained as a thinker, Nietzsche as a person was of exquisite sensitivity, tenderness and refined courtesy in attitude and manners towards the female sex, as others who knew him personally have often emphasised. Nothing in his nature could have made a disturbing impression on me.’

The dissonance between the bellicose Nietzsche of legend and the all-too-human Nietzsche the person is conveyed brilliantly in Chamberlain’s wonderful portrait. After all these years, Nietzsche in Turin remains a most beautiful and evocative – but seldom gratuitous – depiction of this delicate soul, who truly merits the cliché of the tortured artist.

Chamberlain understands Nietzsche’s everlasting appeal well. Foremost, it was his gift as a writer – a writer who wrote in German as if it were French and who assembled prose as if he were composing operas. ‘What he had’, Chamberlain writes, ‘was a wonderful musical way with words. In that sense he was a musician. In that sense he did fulfil his desire to make music the fundament of his creative life.’

Chamberlain’s description of Nietzsche’s liberating philosophy, or psychology, encapsulates his allure as the arch-individualist and ultimate free thinker: ‘He is implicitly inimical to any form of political correctness or mass ideology… Nietzsche was not a proto-Nazi, not a nihilist, not an anarchist.’

Bewitching style and meaty substance – there lies Nietzsche’s everlasting appeal.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist and author of Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times.

Nietzsche in Turin: The End of the Future, by Lesley Chamberlain, is published by Pushkin Press. Order it here.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.