Long-read

Rail strikes: not a return ticket to the 1970s

The class struggle of old bears no relation to today.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Here is the news. Britain may be facing a period marked by conflict and chaos and a lot of uncertainty. But of one thing we can be sure. Contrary to reports elsewhere, in 2022 we are not going back to the 1970s.

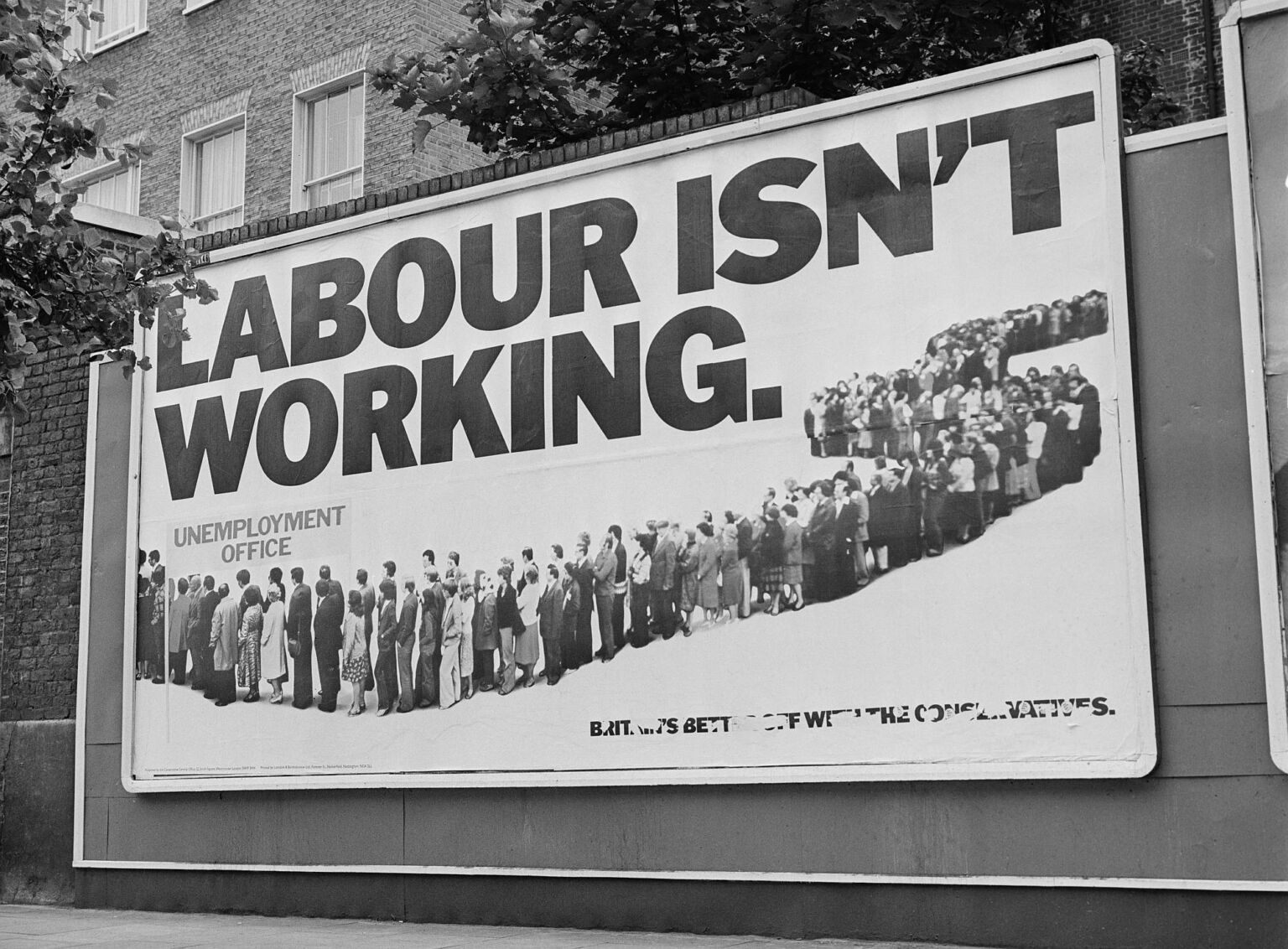

Everybody seems obsessed with viewing this week’s rail strikes as a re-run of the industrial disputes of the 1970s, especially set against the backdrop of the sort of raging inflation last seen 40 years ago. There is much talk of a ‘summer of discontent’ to match the infamous ‘winter of discontent’ of 1978-79, with warnings that industrial action could spread to other sectors of the workforce, from teachers to health workers.

This week, Tory transport secretary Grant Shapps accused the rail workers’ union, the RMT, of taking Britain ‘back to the bad old days’. On Monday, the Sun’s frontpage headline spelt it out graphically, in the style of a railway-station PA announcing the cancellation of a service: ‘We regret to announce that this country is returning to the 1970s.’

On the other side, left-wing supporters of the striking rail workers on social media (tweeting being the closest they get to showing solidarity these days) have hailed the rail strikes as marking the historic return of trade unionism and the class struggle, seemingly hoping to stage a rematch of past battles and reverse old defeats.

‘This is Boris’s miners’ moment!’, announced one viral tweet, evoking bitter memories of the defeat of the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike that finally ended the era of trade-union militancy. (Since political eras rarely match calendar decades, we might best understand the 1970s in this context as lasting from about 1972 to 1985.)

That is why both sides got overexcited by the appearance on the rail workers’ picket line of an elderly Arthur Scargill, the former left-wing leader of the National Union of Mineworkers – now widely seen as either the pantomime villain or hero of past strikes, according to political taste.

In reality, however, a re-run of the battles of the 1970s and early 1980s seems about as likely as a successful Sex Pistols reunion and a mass punk-rock revival. Britain’s economy, workforce and politics have all changed drastically over the past half-century. That was a time when the traditional class divisions and the old politics of left and right still dominated. By contrast, neither side in the current disputes bears much relation to its predecessors.

What is most striking about the national rail workers’ strike – three days of industrial action over pay and threatened job losses – is that it is happening at all. It is the first such strike many people will remember. By contrast, the 1970s were a time of frequent mass industrial action and all-out strikes involving millions of hard-up workers demanding decent wages and working conditions, which at different times led to power cuts, the imposition of a three-day working week and garbage piling up on the streets.

The numbers tell the story. In 1972 in the UK, almost 24million working days were lost due to industrial action. In 1979, the year of the winter of discontent, that figure hit 29.5million days. In 1984, with the start of the last big miners’ strike, more than 27million working days were lost.

By contrast in 2019, the last year for which full figures are available, just 234,000 working days were lost to industrial action in the UK. That was less than one per cent of the total in the peak years mentioned above – despite the British workforce being far larger today than 40 or 50 years ago.

The trade unions of the 1970s were a power in the land, with a peak membership of 13million in 1979; by 2019 about half as many people were in unions, largely in the public sector, their paper membership often meaningless.

There is certainly no reason for misty-eyed nostalgia about those old trade unions. They were run by bureaucratic officials who colluded with Labour governments over beer and sandwiches in Downing Street, doing deals to impose pay restraints on their own members. The big strikes of the era often began as unofficial action by workers sick of their leaders’ inertia, with the union bureaucracy left struggling to catch up with and restrain their striking members. That was true even of Scargill’s NUM leadership in 1984.

Today, by contrast, it might be hard to recognise most trade unions as real workers’ organisations at all. Some of the big unions to the forefront in past strike waves, such as the miners’ and steelworkers’ unions, barely exist now, if at all. Union membership is concentrated in the public sector, often among white-collar professionals rather than the contracted-out manual workers.

Most unions now appear more like an extension of management’s human-resources departments. Many members are more likely to hear from their union via offers of cheap insurance than in branch meetings to discuss collective action. And away from the traditional class struggle, in the culture-war issues of our times, the trade-union leadership has gone increasingly woke (as with the education unions), taking sides against their own members who dare to cross the politically correct line on whether a woman can have a penis.

Little wonder, then, that the RMT – with its seemingly solid, well-organised membership and strident left-wing leadership – can appear like such a singular throwback to another era. But if other workers’ frustration over the cost-of-living crisis spreads, they will need to find new ways to resolve it, rather than fantasising about the often useless trade unions of today somehow staging a re-enactment of the battles of the 1970s.

On the other side of the divide, the contrast is also stark. The British political class of the 1970s was widely derided as an impotent, paranoid, small-minded mess. Yet compared to the political pygmies of today’s elites, they might look more like giants.

Even Edward Heath, the Conservative prime minister between 1970 and 1974, while largely a figure of fun, was a Tory with the gumption to recognise a class war when he saw one. Thus in 1974, in response to another major dispute with the miners, Heath called a General Election and effectively announced that the key issue to be decided was not just the price of bread but ‘Who rules?’. The divided British electorate decided that, whoever ruled, it wouldn’t be Heath. The election led to a minority Labour government under Harold Wilson.

The following year, Heath was ousted as Tory leader and replaced by Margaret Thatcher. After becoming prime minister in May 1979, in the election that followed the ‘winter of discontent’, Thatcher would take on and defeat the old trade unions.

The Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 became more like a civil war, complete with a paramilitary police force occupying the coalfields. Thatcher famously denounced Scargill’s NUM as ‘the enemy within’, which had to be defeated just like ‘the enemy without’ – the Argentine army in the 1982 Falklands War. The ‘Iron Lady’ won three General Elections, destroyed the spectre of ‘union power’ in Britain, and won the eternal hatred of the left.

Despite the rump of the left’s desperate attempts to compare Boris Johnson’s government to Thatcher’s Tories, in reality the contrast is stark. Standing on the sidelines of the rail dispute, these limp Conservatives can only plead that ‘it’s nothing to do with us, guv’nor’, while issuing empty threats of using agency staff to replace the strikers (good luck with that). The Tories’ invoking of the 1970s, claiming that Labour is still in bed with the trade-union reds, has been described as a flailing attempt to blame the next Labour government for the problems of today.

The sight of such pathetic Tories might raise hopes among rail workers or other groups of winning some short-term concessions. But it also means the crisis is likely to drag on into the future, with a government in denial about the depth of the problems we face and clueless about how to address the underlying issues in the UK economy. Unlike the end of the 1970s, there is certainly no Thatcher-type ‘disruptor’ waiting in the Tory wings.

If Boris Johnson’s government might be considered as mere imitation Tories by past standards, then, by the same token, Keir Starmer’s opposition is not really a Labour Party at all. Labour is now a different animal than in the 1970s. The one thing the different Labour parties then and now have in common is that neither can represent the working classes.

By the 1970s, Labour was claiming to be the ‘natural party of government’. From 1964 to 1970 and again from 1974 to 1979 Labour governments were seen as the best option for capitalism to contain the tensions in British society.

Contrary to legend, Labour was never really the party of the working class. It was established at the start of the 20th century as the party of the growing trade-union bureaucracy – to represent the sectional interests of union leaders in parliament while drawing on the votes of millions of working people.

This exploitative relationship reached its nadir in the 1970s ‘social contract’, under which the Labour governments headed by Harold Wilson and then James Callaghan did deals with the leaders of the Trades Union Congress to hold down wages at a time of rampant inflation. As a result, the peak of trade-union membership in the late 1970s coincided with the largest falls in working-class living standards since the Second World War.

The masses demonstrated what they thought of that, first by staging powerful strikes through the ‘winter of discontent’, and then by kicking Labour out and electing Thatcher’s Tories.

What passes for a Labour Party today is partly a product of those defeats. Under first Neil Kinnock, and then more successfully under the New Labour government of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, the party abandoned its historical identification with the labour movement (while of course still taking millions in trade-union donations).

Labour transformed itself into a new elitist party of the metropolitan and later Remainer middle classes. Those political chickens came home to roost in the 2019 General Election, when Labour lost a lot of Brexit-backing Red Wall seats in the north and the Midlands. Now Starmer is trying to coax those working-class voters back, while keeping his petit-bourgeois power base onside.

The result is the risible spectacle of Starmer trying to sit on the fence over the rail strikes, while leading Labour MPs strike empty poses on picket lines, against his express instructions. Labour is left looking a pathetic mess with apparently no more idea than the clueless Conservatives about what to do to resolve the country’s crisis.

The 1970s politics of left vs right is now history. But nothing clear or coherent has yet emerged to replace it. Instead, mainstream party politics has become an elitist blob, a shapeless blancmange. The gap between all of the parties of the past and the masses of today is starkly illustrated by Brexit.

Back in the 1970s, the UK population voted overwhelmingly to join the trading bloc of the European Economic Community. In 2016, the British working classes voted to leave the political bloc of the anti-democratic European Union, against the instructions of every major political party. As Tom Slater argues elsewhere on spiked, the RMT, now hailed as heroes of the class struggle, were previously denounced by the left as racists and reactionaries for daring to side with the majority against the EU and the Remainer elites. These parties and activists locked in the politics of the past are unable to make a case for change today because they cannot channel the popular democratic spirit of the Brexit vote – the greatest working-class revolt in modern politics.

On all sides, the unhealthy obsession with casting backwards and trying to understand the present through the prism of the 1970s is a sure sign of society’s fear of the future and inability to see forwards. Staging such period melodramas is a miserable excuse for political debate and won’t offer any new solutions. We need to start afresh and look to the future.

The 1970s get a bad press. As I wrote on spiked a few years ago, this scapegoating exercise surely says ‘more about society’s disorientation in the present than the sins of the past’. But whatever anybody thinks of the 1970s, it is a bit rich to blame that decade for the crisis we face today. To paraphrase LP Hartley: the 1970s is another country; they do things differently there.

Mick Hume is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Revolting! How the Establishment is Undermining Democracy – and What they’re Afraid of, is published by William Collins.

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.