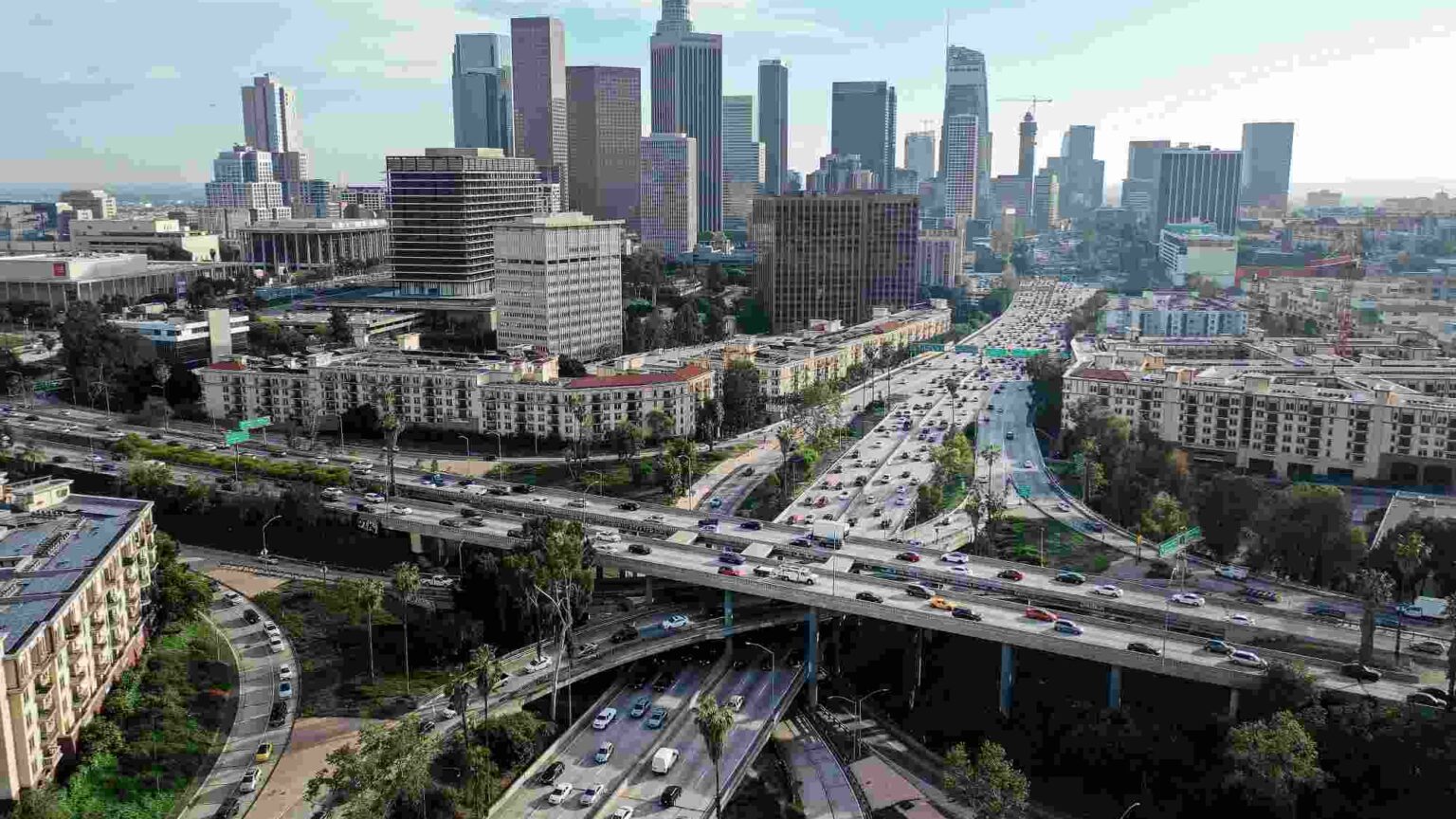

California is at a crossroads

Its oligarchic, tech-reliant economy cannot survive for much longer.

The most recent elections in California resolved little about the future, but did suggest that there’s a growing electoral unease with progressive dogma. This was made most clear in the recall of San Francisco’s arch-radical district attorney, Chesa Boudin, and in the first-place finish of billionaire Rick Caruso, on an anti-crime and anti-homelessness ticket, in the primary race for LA mayor.

The drivers of electoral change are quality-of-life issues, like homelessness, petty crime and a general deterioration of civic order. Yet the biggest issues have hardly been discussed, notably economic trends and policies that underlie the state’s housing problems, entrenched poverty, massive inequality and loss of attractiveness to investors.

To be sure, candidates like Caruso and business interests funding the Boudin recall are aware of the economic issues. Yet they, and for that matter Gavin Newsom, who won a majority in the Democratic primary for California governor, have not focused on the economic crisis that could supplant all other issues in the coming year. The state media, which should be focusing on this, seem more interested in explaining away the economic problems that are clearly facing California.

The key problem is simply this: the state’s economy now depends on a handful of tech companies and their investors to fill its coffers. Capital gains, up roughly five-fold between 2010 and 2020, are likely to tumble this year. The rich, the subjects of hatred on the left, are the ones who support this progressive state. Today, notes the California Franchise Tax Board, the top one per cent of income-earning Californians pay almost half of all personal income taxes, with the top five per cent paying two-thirds.

This is not well understood, least of all by those around Newsom, and is barely discussed among political leaders. For a decade, California has been losing its share in a host of fields, such as construction, manufacturing and professional business services, to other states – notably, Nevada, Arizona and Texas. Investors are building in these places but rarely in California. Last year, on a per capita basis, new business investment in California was one-13th that of Ohio.

As a result, the state has suffered the nation’s worst cost-adjusted poverty rate. Ironically, just as the state has passed a bill backing reparations for descendants of slavery (despite California historically being a ‘free state’), the position of minorities is generally poor. According to the United Way of California, over 30 per cent of California residents – and nearly half of Latinos and 40 per cent of blacks – can’t cover basic living costs even after accounting for public-assistance programmes. In a new report for Chapman University, African-American and Latino Californians’ real earnings ranked between 48th and 50th among the states. Black people in California earn roughly the same, or slightly less, than do their counterparts in Mississippi.

Until now, the tech boom allowed for the state to cover over these contradictions with full coffers that could underwrite housing, education and energy subsidies. But that is changing. So even if Caruso and the Boudin recall backers can curb crime, a lack of economic growth, particularly outside the Silicon Valley, will intensify out-migration and create a greater fiscal gap for the state.

Worse yet, the regulatory regime, backed by the oligarchs, weakens sectors that could make up for the economic losses. But the state seems determined to keep hammering blue-collar, energy-using industries – such as oil, gas, home construction and manufacturing. This means that California, a state with large oil reserves and agricultural production, cannot rely on its analogue strengths. Right now, amid the supply-chain crisis and in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, investing in oil, gas, minerals and food may make more sense than investing in algorithms. California, drunk off stock and property inflation, is in danger of missing a big paradigm shift that could sustain its wealth.

Even tech seems to be shifting away from the state. Key players like Tesla, HP Enterprises and Oracle have moved their headquarters elsewhere. One reason for this is the rise of remote working, which is particularly well-suited to the tech sector; a University of Chicago study demonstrates that a majority of all tech jobs can be done remotely at home or in an office far from the mothership. Critically, most startups now see their future as dispersed and largely virtual.

None of this is to suggest that California will not maintain its pre-eminence in tech, but its centrality is fading. San Francisco, despite not being particularly hard hit by the pandemic in terms of Covid-19 deaths, has suffered among the most severe population and office-space losses in the country. Chipmaker Intel is putting at least $20 billion – the largest private-sector investment in Ohio’s history – into a massive new facility outside Columbus. It is all part of a plan to create what Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger calls the ‘Silicon Heartland’.

Other states, notably in the south and Texas, as well as neighbouring Arizona, are developing their own tech and manufacturing capacities at a rapid rate. Like Intel’s plant, many of the new battery and EV plants are being built in the south or the Midwest. According to the widely regarded CompTIA Cyberstates projections, most of the Top 10 states for tech growth by 2030 will be red ones, including Utah, Nevada, Florida and Texas. In 2019, Texas actually passed California in terms of creating new tech jobs. ‘California used to be the land of opportunity’, Elon Musk remarked recently. But it’s turned into ‘the land of taxes, overregulation… and this is not a good situation’.

So, while Newsom has secured his re-election in 2022, he could live to regret it. California’s situation in the new recessionary reality is more perilous than the governor or his media clique believe. Once the economic issues surface, the state will no longer be able to pretend that Silicon Valley can save its future, while everyone else feeds off the Big Tech cornucopia.

Ultimately, California’s underlying economic problems cannot be solved by a combination of wishful thinking and tech bounties. The high-tech hangover is just starting, and once it settles in the ramifications will be far greater than what happened last night. The Golden State’s political transformation away from progressive dogma may just be a flicker today, but it could become a beacon for change in the years ahead.

Joel Kotkin is a spiked columnist, the presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute. His latest book, The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, is out now. Follow him on Twitter: @joelkotkin

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.