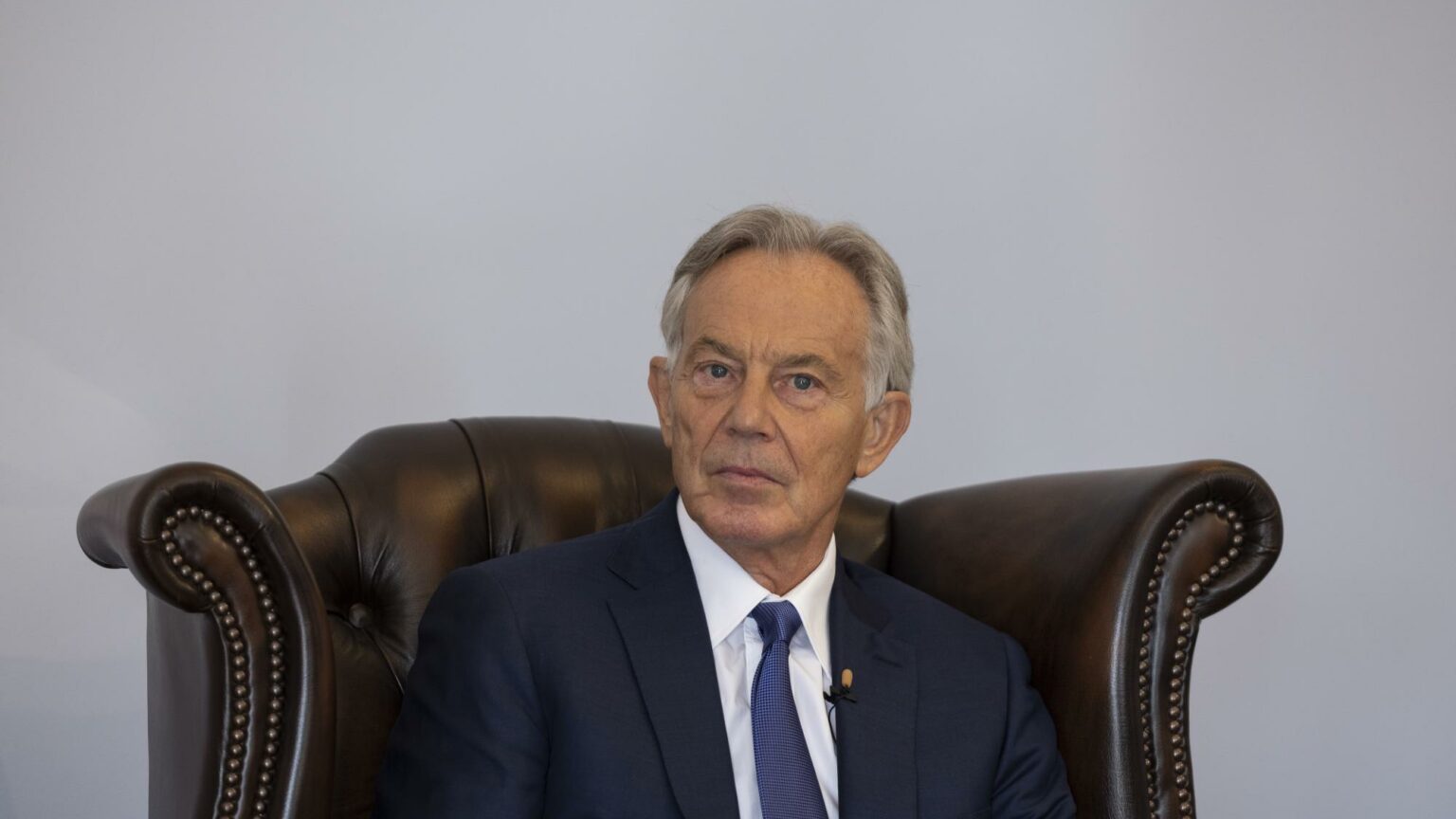

Tony Blair is dead wrong about universities – again

Sending even more people to university won’t help the economy, but it will make degrees near worthless.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Former UK prime minister Tony Blair has done more harm to the British university system than any other political leader in modern times. So it is no surprise to see him attempt to do further damage. This time, he is calling for 70 per cent of young people to go on to higher education, in order to tackle the UK’s productivity crisis.

This is not the first time that Blair has promoted increased participation in higher education as a way to meet economic objectives. Back in September 1999, two years after New Labour’s first General Election victory, he said he wanted to see 50 per cent of young adults going into higher education in the next century, in order for Britain to succeed in the ‘knowledge economy’. Successive governments have supported this attempt to cram more and more young people into higher education. And in 2019, Blair’s target of 50 per cent was finally met.

Turning universities into a means to solve the UK’s economic problems – in this case, the productivity crisis – perverts the raison d’être of higher education. Universities do not exist to raise productivity levels, or improve a nation’s GDP. Their purpose is to develop and disseminate knowledge, and to stimulate young, eager minds in the process.

Moreover, the idea that increasing university participation rates will lead to an increase in economic productivity is fanciful. If there really were a direct causal relationship between increasing the rate of participation in higher education and raising productivity growth, then Britain would surely be undergoing an economic miracle by now. That is clearly not the case.

Only four per cent of school leavers went to university in the 1950s. That figure rose to just 14 per cent by the end of the 1970s. Today, of course, participation rates stand at over 50 per cent. Yet despite the massive increase in the undergraduate population, productivity growth was more impressive in the 1950s and 1960s than it is today. In 1960, for instance, Britain had the highest level of productivity in Europe (measured in gross domestic product per hour worked).

It is the level of investment in innovation and new labour-saving technologies that increases levels of economic productivity, not the quantity of university degrees. Equipping young people with vocational skills and introducing an ambitious programme of apprenticeships would be a far more effective way of enhancing Britain’s economic performance than shipping more and more teenagers off to universities.

But the expansion of Britain’s university population does not just fail to improve our economic performance – it also erodes the academic ethos and the quality of higher education.

This is hardly a surprise. When widening participation becomes an end in itself, the quality of the university experience becomes a secondary concern. The policy of expanding access begs the question: what are you expanding access to? The answer, sadly, tends to be an inferior version of what a university should be.

On paper, of course, everything looks brilliant. There are more students packed into seminar rooms than ever before. Students are achieving higher grades than in the past as well, and the number of young graduates is forever on the rise.

But the reality is very different. A significant proportion of undergraduates are bored out of their minds. They would rather be playing with their phones than attending a seminar or listening to a lecture. Many of my colleagues in academia estimate that around 30 per cent of their students lack any academic interest. They are just hanging in there until they receive their degrees. It would be much better for this unmotivated group to enter the world of work instead, where they might acquire some useful skills.

The large number of intellectually unmotivated students has a negative impact on the entire academic community. Lecturers are often under pressure to accommodate these students’ lack of interest. So they adapt their teaching methods to ensure that these ‘hard to reach’ students will not drop out. This often entails lowering standards and creating an intellectually undemanding environment. And to what end? Many of those who endure such an impoverished academic experience end up in jobs where their paper qualification is irrelevant anyway.

There is still a substantial cohort of intellectually curious students, of course. But unless they are lucky enough to come under the influence of a demanding, no-nonsense academic, they are unlikely to be stretched or intellectually stimulated.

Increasing the numbers of young people going to university effectively turns higher education into further education. If Blair’s new proposal were to be implemented, the standards in higher education would fall to the point where a degree would lose much of its remaining credibility. Students graduating with these worthless degrees would find greater meaning in life, and no doubt be better off as well, if they gained their qualifications in the world of work.

Frank Furedi’s 100 Years of Identity Crisis: Culture War over Socialisation is published by De Gruyter.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.