P&O: why ownership must come home

Global corporate entities are totally indifferent to the fate of British workers.

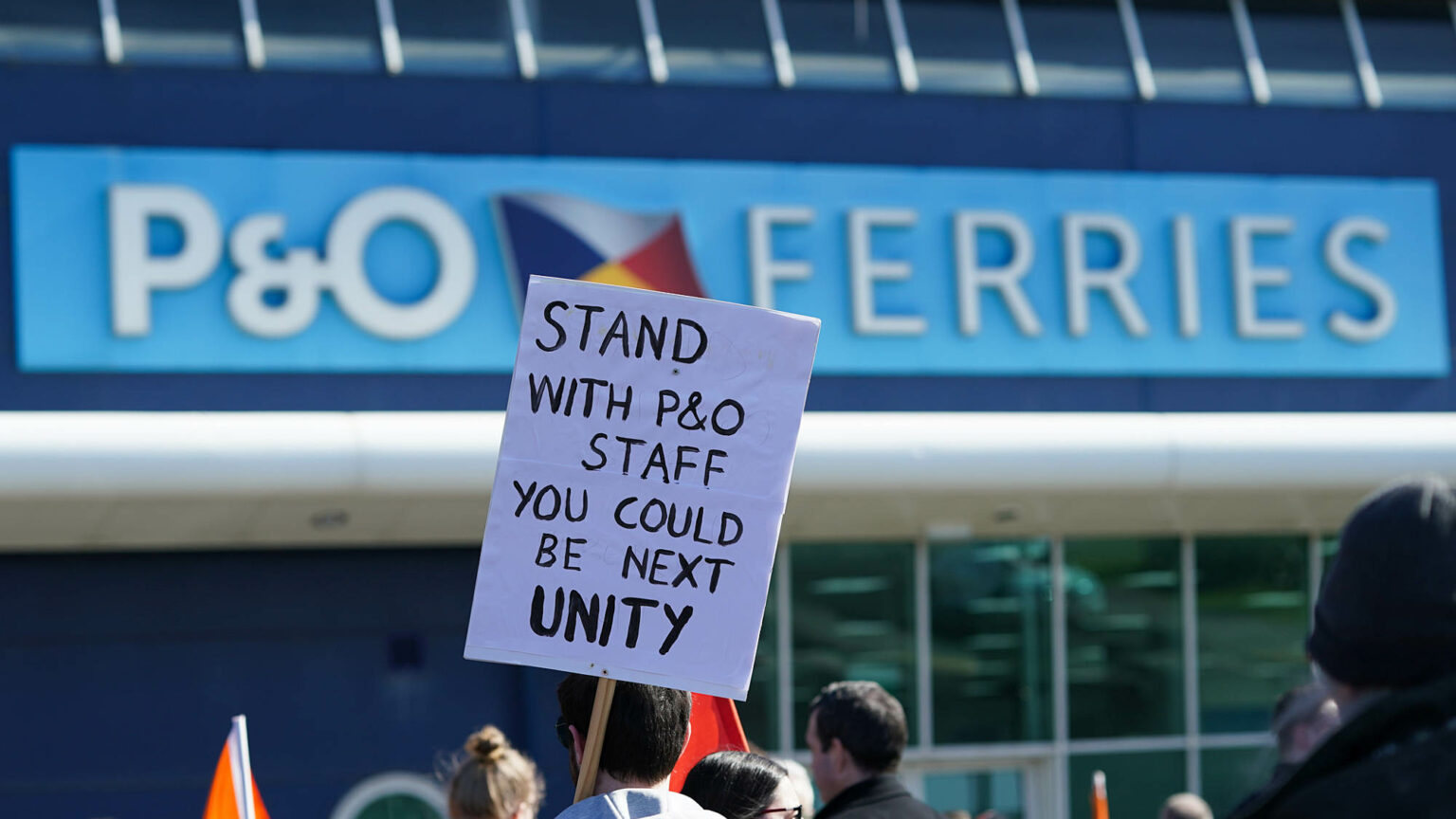

Last week, in a spectacular act of corporate cowardice, P&O Ferries sacked some 800 British workers – gracelessly via a pre-recorded video speech delivered over Zoom. The seafarers, many of whom had given the company decades of service, were largely replaced with cheaper overseas contract labour.

While the sheer brutality and abruptness of P&Os methods have drawn widespread condemnation from unions, politicians, commentators and the government, the sad truth is that P&O’s action is probably, strictly speaking, legal. Its vessels are registered overseas and what it pays its crew on the open seas is beyond the reach of UK employment law. This case may also be a dry run for more ‘fire and rehire’ activity to come. P&O’s actions raise many issues around corporate irresponsibility and the general powerlessness of employees, but at the centre of this outrage is the question of industrial ownership: who owns our companies and to whom are they loyal?

The ultimate decision to discard these British workers may well have been made thousands of miles away by P&O’s parent company, DP World, which is part of Dubai’s sovereign wealth fund.

The remoteness itself tells a story. An executive in Dubai lacks a day-to-day connection to the workers he or she might sack in Hull or Dover. And it is far easier to dismiss people by electronic means from an office based abroad, rather than having the courage and the decency to do it face to face.

We shouldn’t be surprised at this state of affairs. Successive British governments have structured our economy with complete indifference to the questions of what is made where and by whom and, ultimately, who owns and controls production. For years now the old social-democratic idea that markets are justified by their social function has been derided as quaint. But to view our low-wage economy and hollowed-out labour market as satisfactory is to live in an alternative world.

Our government has waved through countless foreign takeovers of UK industrial assets – Cadbury, Rowntree Mackintosh, Jaguar Land Rover, ICI, British Steel and Pilkington, to name a few – without understanding that ownership and loyalty to place matter. American food conglomerate Kraft closed the Cadbury factory in Bristol in 2011, just months after taking it over, despite making pre-acquisition assurances to the contrary. Rootless, global capitalism has no regard for locality or place. It treats workers not as human beings, but as expendable units.

Successful industrial economies should not operate like this. Japan doesn’t. South Korea doesn’t. Why? Because in South Korea companies are basically patriotic – and for a reason. They see industry as a strategic necessity for Korean society. In contrast, the people who govern us in Britain tend to take a short-term view. Selling off our industrial assets can make quick money for some people. But the executives who end up owning these companies operate globally, and are completely detached from the countries their decisions affect. They are part of a system which can’t determine the difference between cost and value, and which has pushed the UK into near-beggary amid the recent pandemic. They regard Britain – as they do all other countries – merely as a market.

The heart of the problem is the ease with which executives pursue narrow corporate interests – and often their own interests – above those of society. Our political class has forgotten that corporate interests are very often in direct conflict with the national interest – and with the needs of employees and their families, and the towns and cities they live in. The very idea of prioritising the interests of one’s fellow countrymen and women is now ignored and often treated as taboo.

Christopher Lasch highlights this collapse of national solidarity in his seminal 1994 book, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, in which he argues that our elites have become tourists in their own countries. According to Lasch, our elites have morphed into ‘world citizens, but without accepting any of the obligations that citizenship in a polity normally implies’.

What typifies the modern global corporation is its lack of obligation to any nation. There is no sense of reciprocity. P&O was happy to receive millions of pounds in furlough payments from the British state during the pandemic. But then, it shamelessly repaid the favour by abruptly sacking British workers. P&O’s pension has a £146million deficit which might, due to its connection with the Merchant Navy Ratings Pension Fund, result in the UK taxpayer being subject to liabilities running into the millions. As is so often the case in our rigged system of contemporary capitalism, the profits are private but the losses are public.

Much of this is the direct result of economic policy. Our increasingly open and flexible labour markets have eroded the traditional loyalties between labour and management. Indeed, the sense that they have a shared fate has, in cases such as P&O, been utterly shattered. Unless this sense of mutual obligation is repaired, both employers and employees will become less willing to invest in each other to the detriment of both, and to the wider economy.

How to remedy this? A public boycott of P&O is unlikely to be successful given the hold P&O has on cross-channel ferries. Some have suggested that London Gateway and Southampton – ports owned by DP World – should be omitted from the government’s new ‘freeport’ scheme. After all, why reward bad corporate behaviour? I think this is unlikely, given the Tory government’s free-market ideology and alleged cosiness to DP World. What is striking is that the foolishness of allowing strategic ports to fall into foreign hands seems not to have occurred to those who govern us.

Whatever action is eventually taken when it comes to P&O, we are heading towards a period of de-globalisation in which the question of ownership and control of national strategic assets will become impossible for our rulers to ignore. It is time for JM Keynes’s advice to be heeded – namely, that it is preferable for production to be as local as possible. Mutual loyalty between management and workers can and must be gradually repaired.

Ironically, the lie at the heart of our present industrial settlement is revealed by the names of two of P&O’s mightiest ships. The Pride of Hull (built in Italy) and the Pride of Kent (built in Germany) are registered in Cyprus and the Bahamas respectively.

Pride? Not yet…

William Clouston is leader of the Social Democratic Party.

Picture by: Getty Images.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.