Trigger warnings have jumped the shark

Apparently Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea is potentially traumatising.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

So a Scottish university has now put a trigger warning on Ernest Hemingway’s novel, The Old Man and the Sea (1952). According to reports from last week, history and literature students at the University of the Highlands and Islands have been warned that Hemingway’s classic contains ‘graphic fishing scenes’.

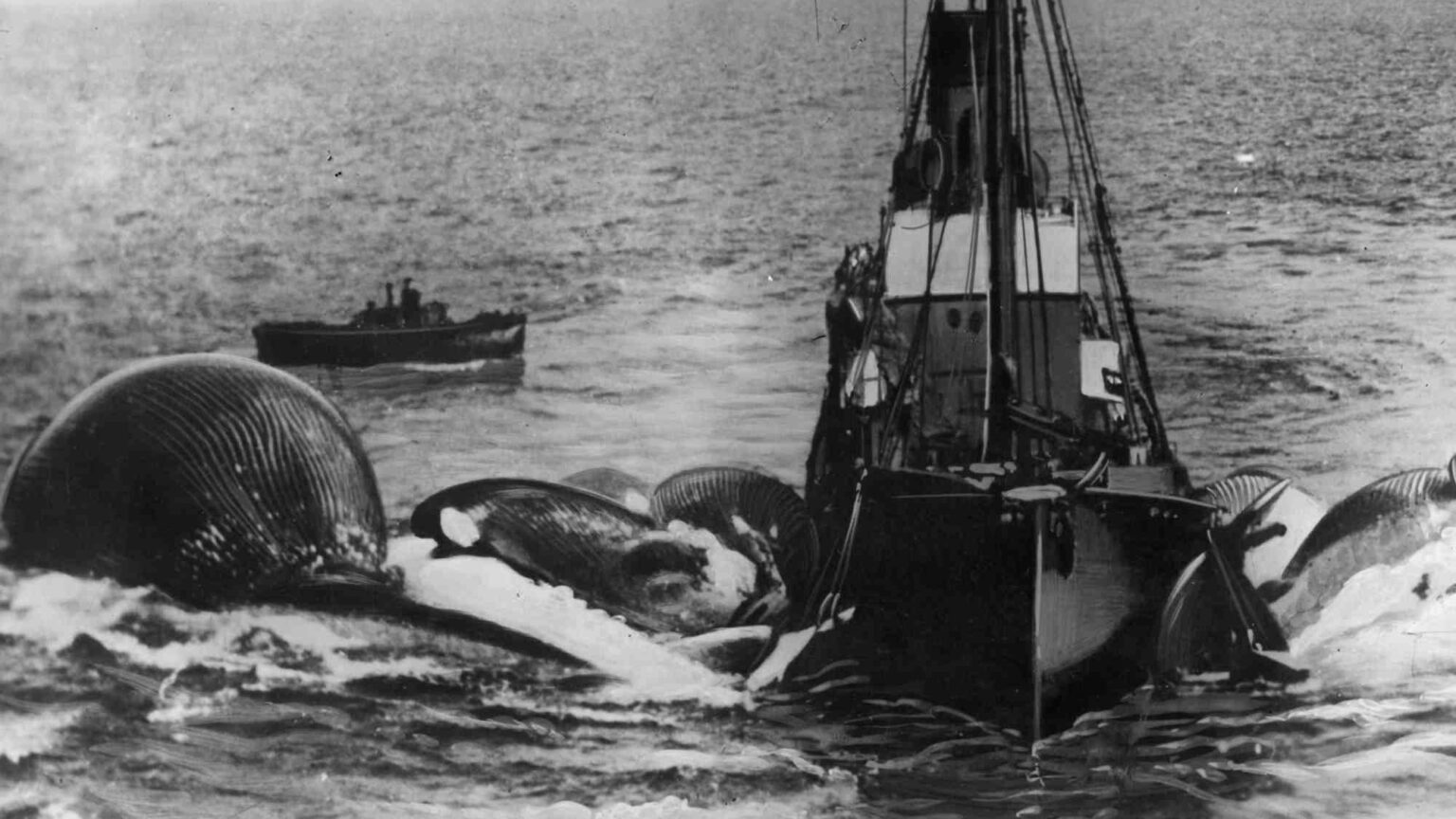

Which it does, of course. The Old Man and the Sea describes a lone Cuban fisherman called Santiago struggling to catch and kill a giant marlin, only for the fish to be stripped of its flesh by sharks. The fisherman’s travails go unrewarded, and his heroic struggle unrecognised. From this tale, Hemingway captures something of the truth of man’s eternal battle with nature.

Not that the university seemed to care about the actual meaning of Hemingway’s novel. It was far more worried about the traumatising effect it might have on students sensitive to, er, depictions of fishing. Hence it was happy to defend its decision, stating that ‘[trigger] warnings enable students to make informed choices’.

This absurdity is merely the latest example of a now common practice at British universities. Others have applied trigger warnings to such classics as To Kill a Mockingbird, Kidnapped and Jane Eyre. Ironically, even Nineteen Eighty-Four, a novel that depicts a world of censorship and thought control, could not escape a trigger warning. Still, warning that a novel about a fisherman’s merciless battle with nature contains ‘graphic fishing scenes’ is daft even by the absurd standards of campus censorship.

A Guardian columnist has warned against overreacting to the Hemingway incident. Trigger warnings are little more than a right-wing moral panic, she says. ‘An overzealous attempt to inform students about content they may find upsetting is not something to be outraged by’, she says. Given that the same columnist has opined on such important issues as ‘Why Ivanka Trump’s haircut should make us very afraid’, perhaps her judgement is not always the most reliable.

Besides, we really should be concerned by trigger warnings. They effectively permit, perhaps even encourage, students to avoid reading certain books. And in doing so they keep students in their intellectual comfort zones, stunting their cultural and educational development.

This desire to protect students from difficult material not only narrows their horizons – it also imposes a certain worldview on students. After all, what is considered ‘triggering’ is a reflection of the values of those slapping the warnings on works of literature. In this case, warning students that The Old Man and the Sea contains graphic fishing scenes reflects the metropolitan worldview of those with no connection to working the land or the sea. After all, why on earth should a depiction of man’s attempt to extract food from the ocean be considered potentially upsetting?

Universities ought to provide students with the opportunity to challenge their preconceptions and test out new ideas. Indeed, they ought to be centres of intellectual experimentation. The rise of trigger warnings suggests that universities are instead turning into factories of conformism – places in which students are encouraged not to confront ideas they might find difficult or challenging.

Moreover, as Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt note in their 2018 book, The Coddling of the American Mind, issuing trigger warnings has not just promoted intellectual conformism – it has also cultivated intellectual and emotional fragility, too. Trigger warnings, they explain, reduce the robustness of discussion and the resilience of individuals, and, ultimately, increase young people’s sense of anxiety.

Trigger warnings may be silly. They may be the product of oversensitivity. But they really are having a serious impact on young people’s development.

Alexander Adams is a writer and artist. His most recent book is Iconoclasm, Identity Politics and the Erasure of History (Societas, 2020). His website is here.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.