War, peace and ‘illiberal democracy’

Tom Slater reports from Hungary, as conflict rages on its border and Hungarians prepare for the polls.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Hungary goes to the polls next month. Fidesz’s Viktor Orbán, now the EU’s longest-serving leader, is seeking a fourth consecutive term as PM. Orbán has dominated Hungarian politics for the past 12 years, presiding over super-majorities in parliament and reshaping Hungary in his image. But the race this time around is close, and observers across Europe have taken a keen interest.

An opposition coalition has formed, spanning the far right to the far left, fronted by a small-town conservative mayor, Péter Márki-Zay. The backdrop seemed set. Amid a fierce battle between Budapest and Brussels over the Hungarian government’s alleged ‘rule of law’ breaches, Western media talked up the election as a key battle between the institutions of the European Union and its more sovereignist, right-wing member states.

Then history intervened. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – with which Hungary shares an 85-mile border – has of course changed everything, as refugees arrive and war rages again on the continent. But the conflict has also highlighted the difficult position which this small Central European nation has long occupied in European politics.

Speaking to spiked in Budapest last week, as Vladimir Putin’s forces rolled over the borders into Ukraine and left the world reeling, Fidesz ministers and spokespeople were swift to condemn the invasion and stress their commitment to EU unity – and to challenge the notion that their party is too chummy with Putin.

Hungary’s relatively close relationship with Russia in recent years, particularly in relation to energy cooperation, has often been portrayed as dubious in the Western European press. A Politico piece last week namechecked Viktor Orbán as one of ‘Putin’s European pals’ who was now expected to ‘eat his words’. A few days earlier, a baseless rumour did the rounds in the media, suggesting Hungary might block EU sanctions against Russia.

Everyone I spoke to from the government was quick to rebut this. ‘We condemn the Russian aggression, which is violating international law and the sovereignty of an independent state’, says Balázs Orbán, political director to the prime minister (no relation), speaking to me mere hours after the full invasion began. ‘We are ready to stand united with our European and NATO partners.’

‘Hungary has no special relationship’ with Russia, says Zoltán Kovács, secretary of state for international communications and relations. Given most of Europe is dependent on Russian gas, he accuses Western European nations of having a ‘Janus-faced kind of policy with Russia, cutting big deals in the background’ while criticising Hungary for its own dealings with Russia.

When Putin and Orbán met, for the eleventh time, in January, the Hungarian PM was once again presented as a Russian stooge. Kovács rejects this, painting the relationship as purely pragmatic: ‘Hungary has made only a recognition that to be able to maintain a workable relationship with a partner, in this case Russia, you need basic respect, and the recognition that it’s only going to work when that’s in a normal set-up, rather than a hostile set-up.’

‘The strategy which was followed in connection with Russia, by the important big players, it turned out this is a dead-end street’, says Balázs Orbán, discussing how we got here. Was it a mistake for the West to dangle NATO membership in front of Ukraine, thus antagonising Putin and / or giving him a pretext to invade? ‘I don’t want to judge that, but I see what I see. It’s ended up with war, and ended up with the collapse of the Ukrainian state’, he says.

The Hungarian government’s position on Russia and Ukraine is complicated, informed by a complicated history. It has long blocked NATO-Ukraine talks over what it calls the discrimination suffered by ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine. The government refuses to send arms to Ukraine or be drawn into the current conflict, while condemning the invasion and opening its borders to refugees.

While Hungary has just dropped its opposition to Ukraine’s future EU membership, the government continues to walk a difficult line. Fidesz says it is unrealistic to cut ties with Russia and has offered Budapest as a venue for peace talks. But the leadership of this former Communist state – whose 1956 uprising was crushed by Soviet tanks – is hardly relaxed about an irredentist Russia, either.

‘What would work, according to our understanding, is a reasonable, strong European military’, Balázs Orbán says, bringing him into a perhaps unlikely alignment with French president and self-appointed leader of the EU, Emmanuel Macron. ‘Without a military, you can be right but it does not matter… So you need to be powerful. And right now the European powers are not powerful enough.’

Brussels vs Budapest

A week on from our conversation, and now even Germany is rearming – the Ukraine crisis having upended all manner of geopolitical certainties. But this rare point of unity between eastern and western EU member states remains just that – rare. Indeed, the big story in Brussels before the outbreak of war on its eastern flank was the latest salvo in the EU’s protracted legal battle with Hungary and Poland.

Brussels is currently withholding billions of euros in funding to both countries over what it calls ‘rule-of-law breaches’. Last month, Hungary and Poland lost their case at the European Court of Justice, challenging the legality of the EU tying Covid recovery aid to compliance with these standards. Both nations have been accused by Brussels in recent years of undermining media freedom, LGBT rights and the independence of the judiciary.

The ECJ claimed its ruling was narrowly focused – that funding can only be withheld where rule-of-law breaches could affect its sound financial management. But Budapest doesn’t buy this, not least because the so-called conditionality mechanism emerged in the context of outrage at Hungary over a new law that bans the promotion of homosexuality and transgenderism to children.

Fidesz says the law is about protecting parents’ rights over the content of sex education. But it was widely condemned as illiberal, homophobic and an unconscionable moral outrage. Last summer, Dutch PM Mark Rutte said the law proved Hungary ‘has no business being in the European Union anymore’. EU infringement procedures were launched shortly after. ‘Europe will never allow parts of our society to be stigmatised’, thundered European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen.

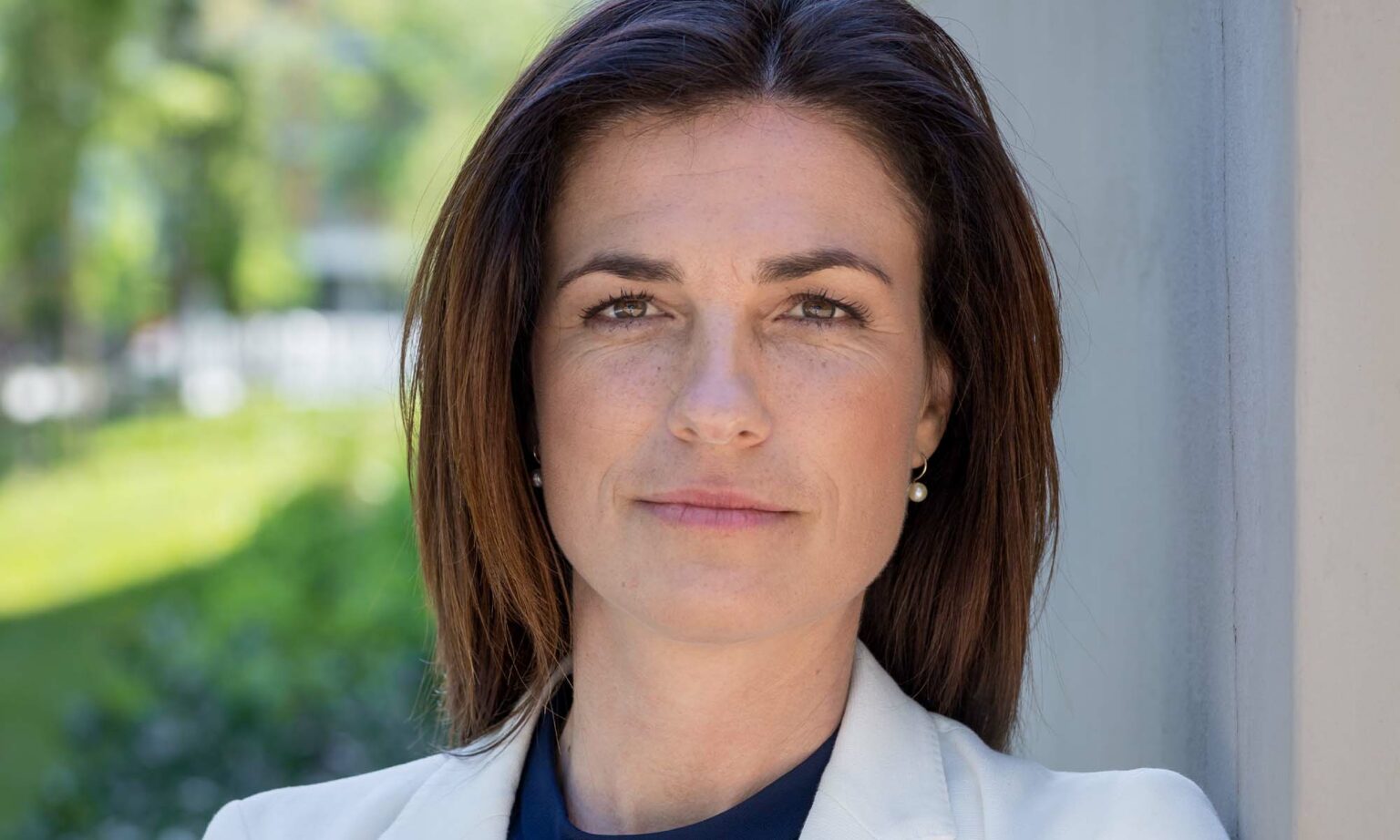

Judit Varga, Hungary’s justice minister, says the mechanism is a ‘blackmailing tool’ that is being wielded by the dominant EU players to enforce conformity. ‘This is a political majority which would like to force its preferences, its political position, on other countries’, she tells me. ‘When it comes to the question of migration, or when it comes to the question of family policy, it is not a legal question, it is a question of ideology or political position or national, constitutional identity… It has nothing to do with legality.’

On election day Hungarians will also cast their votes in a referendum on the new ‘family protection’ law. This harks back to 2016, when Hungary held a referendum on EU migrant quotas, which Brussels was then trying to push on member states in the wake of the migration crisis. Once again, the government hopes to secure a mandate and then dare the EU to challenge it. ‘I expect our partners to respect the democratic decision of our nation’, Varga says.

Naturally, the conversation turns to Brexit. Brussels, Varga says, took precisely the wrong lesson from Britain’s shock vote to leave the EU – responding to this huge electoral rebuke to European integration by simply pushing for more of it and smearing British voters: ‘They did not take the energy to rethink their behaviour. They blamed the UK. They blamed the UK citizens because of their choice. Is it democratic not to respect the democratic decision?’

Hungary is a committed – albeit rebellious – EU member state. For all the nation’s battles with Brussels, no major national figure advocates leaving. But the government is one of the key forces in the EU pushing for a union made up of sovereign nation states, rather than subjugated member states. This is a struggle, Varga tells me, that has become much more difficult since Eurosceptic Britain left.

Illiberal democracy

Where discussion of Hungary is concerned, one phrase haunts the comment pages like no other – ‘illiberal democracy’. It harks back to a 2014 speech, in which Viktor Orbán said his government aimed to create an ‘illiberal state’ in Hungary. Staunchly conservative and anti-immigration, there is much in Fidesz’s programme that is illiberal in the more traditional sense of the word. But in the prime minister’s rendering, the phrase means something deeper – prizing the community over the rights of the individual, and taking a ‘national, particular approach’ to governance.

That one speech has fuelled alarm in liberal quarters ever since. Concern about Hungary’s alleged slide into authoritarianism perhaps reached its crescendo in March 2020, when in response to the Covid-19 outbreak the government passed an act in parliament empowering it to rule by decree on pandemic matters indefinitely. Hungary was promptly dubbed ‘the first dictatorship in the EU’.

As is so often the case with Western coverage of this government, the reality was much more complicated. The act was a democratic outrage, of course, but then so were many other similar laws that were passed across Europe in response to the pandemic. (In Britain, the government used existing law to allow it to rule by decree.) The Hungarian act went further than others in some key areas, and it had far fewer safeguards. But Orbán’s more shrill critics looked more than a little silly when he handed back his supposedly long-coveted dictatorial powers three months later.

Conservatives of the world unite

While Fidesz continues to stoke international outrage, it is also collecting admirers – particularly on the American right. Fox News host Tucker Carlson broadcast his show from Budapest last year, singing Orbán’s praises. Christian conservative writers, like Rod Dreher, are now regular fixtures on the Budapest intellectual scene. Later this month, Hungary will become the first European city to host the Conservative Political Action Conference. Just as Cuba once served as a kind of moral refuge for frustrated American leftists, so Hungary is now the conservative’s hope in a heartless world.

Balázs Orbán has been instrumental in forging these intellectual links. He has spoken at conferences of Anglo-American ‘national conservatives’, intellectuals who embrace nationalism and reject neoliberal economic orthodoxy. Orbán’s book, The Hungarian Way of Strategy, has recently been translated into English. The dust jacket bears a raving quote from Carlson.

In response to recent electoral setbacks for right-wing political parties, from the US to Israel, Balázs seems keen to forge a kind of national-conservative international – a Conintern, if you will – of like-minded politicians and intellectuals. ‘We want to understand them, we want to get to know them, we want to support them’, he says. ‘It’s always important to understand that you are not alone.’

Orbán also seems keen to use his contacts in America, Britain and elsewhere as a kind of early-warning system for whatever socio-cultural exports, emerging out of woke activism, might be headed his way. ‘Because we are part of the Western civilisation, all the problems which are emerging, and social conflicts which are emerging, in that civilisation, these are affecting Hungary’, he tells me.

He presents the upcoming referendum as almost a pre-emptive strike against gender ideology: ‘We try to follow very closely what is going on, because sooner or later it will come in. That’s what happened on the gender issue. That’s why the government made the decision that, immediately, before this whole issue starts, we should ask the opinion of the people. They can tell us what they want to do.’

‘Let us decide’

Whether we’re talking about the EU’s technocratic diktats, or the mini cultural revolutions bubbling over from the Anglosphere, Fidesz is keen to resist any external impositions on Hungary’s democracy and way of life. You don’t need to support its hardline stance on immigration, its social conservatism, or its more censorious attempts to protect what it sees as traditional values, to recognise it must have a right to forge its own sovereign path.

Of course, how democratic this so-called illiberal democracy really is remains a fiercely contested topic. Fidesz has serious questions to answer over corruption and media ownership. It has clearly used its super-majority to reshape institutions in its interests. But you don’t have to spend much time in Hungary to realise it clearly isn’t the tinpot dictatorship of Western journalists’ fever dreams.

In seeking to defend liberal values, we shouldn’t foist them on others. Doing so defeats the purpose. The core of liberalism is tolerating cultural and ideological differences, and challenging ideas we dislike through debate rather than diktat. And it is certainly not the job of the EU or anyone else to blackmail an elected government or dictate the values that a sovereign nation state must uphold.

Over and above the social issues, it appears it is the Hungarians’ insistence on national sovereignty that most rankles the pro-EU set. Indeed, for all the handwringing about Hungary’s ‘homophobic’, ‘far right’ turn under Viktor Orbán, few in the Western media seem to have noticed that opposition leader Péter Márki-Zay is just as conservative and anti-immigration as Fidesz, and presides over a coalition that includes the until recently fascist Jobbik party.

European politics is transforming before our eyes. This was a week in which decades happened. One after another, old certainties have been turned on their heads. The geopolitical implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine certainly make Brussels’ beef with Hungary looks relatively trivial. But as the EU tries to burnish its authority and remake itself in the shadow of war, its inbuilt disdain for national sovereignty is unlikely to fall by the wayside.

‘Let us decide. And please – I’m just requesting, international actors – try to refrain from intervening’, says Judit Varga, looking ahead to the election. She doesn’t seem to be holding her breath.

Tom Slater is editor of spiked. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Slater_

Picture by: Getty

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.