Long-read

The catastrophe of the Covid models

How SAGE’s junk science brought us to the brink of lockdown.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It is easy to forget how close we came to having Christmas stolen for a second time. As England says farewell to the ‘Plan B’ restrictions, it seems unfathomable that there were people who wanted to lock the country down in response to a lot of mostly young, mostly vaccinated Londoners catching a mild strain of SARS-CoV-2 during the Christmas party season. And yet for several weeks last month the demands for tougher restrictions became a deafening roar. Give Boris Johnson his due. Under intense pressure from the media, the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats, SAGE, Independent SAGE, the mayor of London, the British Medical Association, several cabinet ministers and every blue heart / #FBPE account on social media, he refused to ‘follow the science’.

Everything the government has got right on Covid-19 in the past 12 months has happened when it ignored ‘the science’. If the modellers hadn’t made such fools of themselves in the summer and autumn of 2021 they might have been taken more seriously by the government in the winter. As it was, their incompetence had seeded enough doubt in Johnson’s mind for him to resist going beyond ‘Plan B’ despite almost every ‘scenario’ modelled telling him that hospitalisations and deaths from the virus would exceed anything England had ever seen before.

Nevertheless, it was a close call. On 21 December, Johnson delayed making a decision on whether Christmas would be allowed to go ahead as normal while he awaited a report from Imperial College about the severity of Omicron. When this was published the following day it showed a 40 to 45 per cent reduction in the risk of hospitalisation compared to Delta, and a 50 per cent reduction in risk for people who had a prior infection.

This belated admission of Omicron’s ‘mildness’ changed the game. Less than a week earlier, the same team at Imperial College, led by Professor Neil Ferguson, had said they could find ‘no evidence… of Omicron having different severity from Delta’. On the day before that, the chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, had appeared on television telling the nation that ‘there are several things [about Omicron] we don’t know but all the things we do know are bad’.

This was wilful blindness. By mid-December, everything we needed to know about Omicron had been explained to us by doctors in South Africa over and over again. They told us that it was much less severe. They told us to expect a large number of ‘incidental’ cases involving people who were in hospital with Covid but were not in hospital because of Covid. They told us to expect more children to be affected but with only very mild symptoms. They told us that Omicron patients rarely needed to be put on ventilation. They told us that there were relatively few deaths despite high levels of infection. All of this is now apparent in the UK’s healthcare data.

Dr Angelique Coetzee of the South African Medical Association repeatedly told British journalists that Omicron was a milder variant in late November. By mid-December, when the statistics from South Africa had borne out everything she said, she warned that ‘Britain was overreacting’.

The real-world evidence was clear but, as is often the way in public health, computer modelling took precedence over the real world. The modelling overwhelmingly pointed to disaster and the Covid catastrophists went out of their way to downplay the significance of the South African data. People who had previously dismissed the protective effect of immunity from prior infection suddenly declared that South Africa had got off lightly thanks to its earlier waves. South Africans were younger, they said. It was summer there, they said. Some even suggested that the authorities were lying about the severity of Omicron to get South Africa off the red list.

Nowhere were these sentiments more strongly held than at SAGE meetings. The minutes of its meeting on 1 December simply declared that ‘South Africa is not the UK’. Did Omicron have a shorter generation time than Delta? This, said SAGE, was ‘unknown’. Was Omicron less severe than Delta? This was ‘also unknown’.

By 7 December, SAGE had grudgingly admitted that ‘early indications from South Africa suggest less severe disease in those hospitalised when compared to previous waves’, but it hurried to explain this away, saying ‘this likely reflects at least in part the characteristics of those being admitted to date, who are younger than in previous waves’. In any case, SAGE said, ‘a modest reduction in severity would not avert high numbers of hospitalisations if growth rates remained very high’. As late as 16 December, SAGE was insistent that it was ‘still too early to reliably assess the severity of disease caused by Omicron compared to previous variants’.

SAGE had far fewer doubts about what was happening in England and what needed to be done about it. Minutes from the SAGE meeting on 8 December noted that ‘in almost all scenarios consistent with estimated Omicron growth’ England would experience a peak in hospitalisations higher than anything it had seen before. The only way to avoid this was by bringing about a fall in transmission ‘similar in scale to the national lockdown implemented in January 2021’. In case the government didn’t take the hint, SAGE added that ‘it is highly likely that very stringent measures would be required to control growth’.

SAGE acknowledged that one of the models had suggested that hospitalisations might not exceed previous peaks if Omicron was only 10 per cent or 30 per cent as severe as Delta, but it effectively dismissed this possibility, saying that there was ‘no strong evidence that Omicron infections are either more or less severe than Delta infections’ and that it would take at least four weeks before it was possible to know either way.

On 16 December, SAGE again pushed for urgent restrictions. ‘Without intervention beyond those measures already in place (“Plan B”)’, it said, ‘modelling indicates a peak of at least 3,000 hospital admissions per day in England… If the aim is to reduce the levels of infection in the population and prevent hospitalisations reaching these levels, more stringent measures would need to be implemented very soon.’

Two days later, SAGE met again and the message was the same: ‘Scenarios that assume no further restrictions beyond “Plan B” generally lead to trajectories in daily hospital admissions in England that have a minimum of 3,000 hospital admissions per day at their peaks, with some scenarios having significantly worse outcomes during the first few months of 2022.’ Hammering the pro-lockdown message once again, SAGE added: ‘To prevent such a wave of hospitalisations, more stringent measures would need to be implemented before 2022.’

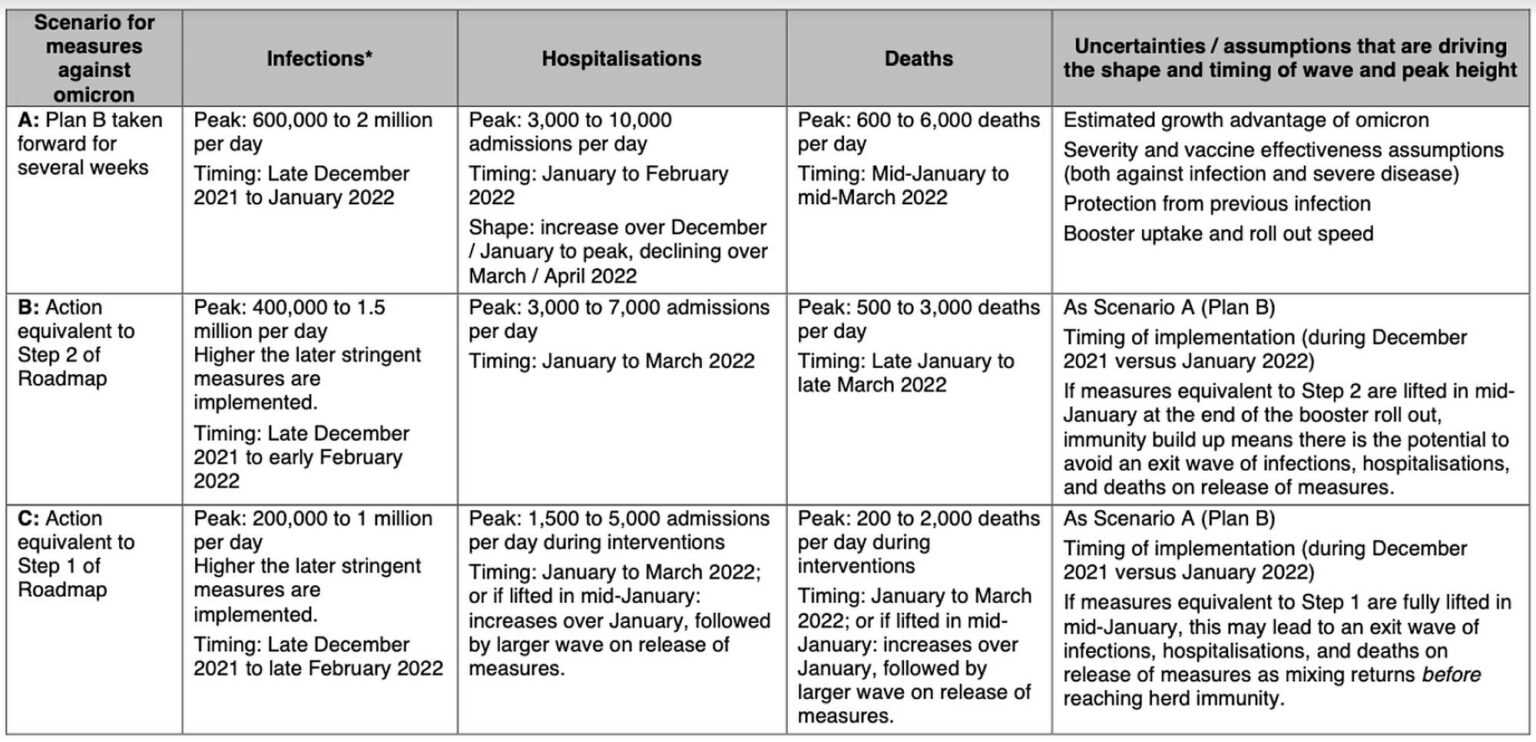

Having taken all the modelling into account, SAGE produced a table that showed in stark terms what the future held if the government stuck to ‘Plan B’. With the usual risible caveat that ‘these are not forecasts or predictions’, they showed a peak in hospitalisations of between 3,000 and 10,000 per day and a peak in deaths of between 600 and 6,000 a day. In previous waves, without any vaccines, deaths had never exceeded 1,250 a day.

The government was effectively given an ultimatum. SAGE offered Johnson a choice between the disaster that would surely unfold and a ‘Step 1’ or ‘Step 2’ lockdown, both of which had been helpfully modelled to give him a steer. ‘Step 1’ was a full lockdown as implemented last January. ‘Step 2’ allowed limited contact with other households but only outdoors.

In the event, as we all know, Boris Johnson ignored the warnings and declined to implement any new restrictions on liberty. A few days later, Robert West, a nicotine-addiction specialist who is on SAGE for some reason, tweeted: ‘It is now a near certainty that the UK will be seeing a hospitalisation rate that massively exceeds the capacity of the NHS. Many thousands of people have been condemned to death by the Conservative government.’

It did not quite turn out that way. Covid-related hospitalisations in England peaked at 2,370 on 29 December and it looks like the number of deaths will peak well below 300. This is not just less than was projected under ‘Plan B’, it is less than was projected under a ‘Step 2’ lockdown. The modelling for ‘Step 2’ showed a peak of at least 3,000 hospitalisations and 500 deaths a day. SAGE had given itself an enormous margin of error. There is an order of magnitude between 600 deaths a day and 6,000 deaths a day and yet it still managed to miss the mark.

Moreover, around half the hospital admissions in the Omicron wave are ‘with Covid’ rather than ‘because of Covid’ and around a quarter of the deaths are not primarily due to Covid. Neither of these statistics will greatly surprise doctors in South Africa, but they will come as a surprise to the modellers, just as it came as a surprise to them that cases didn’t rise in the summer after ‘Freedom Day’; reopening the schools in March last year didn’t lead to a surge in infections; and hospitalisations didn’t reach 1,000 a day in October (their model projected a minimum of 2,000).

Being constantly surprised by events isn’t a happy position to be in if your job is to make predictions (sorry, projections). Covid modelling has sometimes been unfairly criticised. Neil Ferguson’s team famously produced a model in March 2020 which suggested there would be 500,000 deaths in a ‘do nothing’ scenario. This did not happen because the government did not do nothing. The hypothesis was never tested and it is silly to claim that the model was ‘wrong’ on the basis that fewer than 500,000 people died.

A more valid criticism is that the models do not adequately account for human behaviour. Covid had the potential to kill 500,000 people in 2020 but it was unlikely they would have all died in one wave, as Ferguson’s model suggested, because individuals would have hunkered down to some extent.

Predicting human behaviour in a pandemic is not easy, but most of the models don’t even try. If the modellers had noticed the international football tournament taking place in mid-summer they might have done a better job of predicting when the July spike in cases would end. If they noticed that the pubs are always quiet in January they might have made a better stab of predicting what is happening now.

Some understanding of human behaviour would seem to be the minimum requirement if you are going to try to chart the course of a virus that spreads from human to human. If you ignore this and you ignore all the data coming out of a country that has direct experience of the virus you are studying, your model will be worse than useless.

This is not a game. It is not an arcane academic dispute. This junk science brought us to the brink of lockdown. The modellers would never admit this because they take no responsibility for the way their irresponsible number-crunching is interpreted. The great conceit is that the modellers produce projections rather than forecasts and that SAGE merely advises on one aspect of policy. When pushed, modellers, such as Graham Medley, the head of SPI-M (which does the terrible modelling at SAGE and are not to be confused with SPI-B, which does the terrible behavioural science), are keen to stress that they can only help with the health statistics and it is for politicians to ‘balance the harms’ and take the economic and social costs into account.

That’s certainly how it should work but it isn’t what happens in practice. What actually happens is the modellers come up with a range of nightmare scenarios which SAGE tells the government can only be avoided by taking away people’s freedom, preferably in the form of a lockdown. If the government fails to act, it is accused of ‘dithering and ignoring the latest modelling’. SAGE members pop up on the radio – always ‘speaking in a personal capacity’ – demanding ‘more intense control measures’ and declaring that ‘we need to act now’. They are not naive children playing with matches. They are arsonists.

Look, no one can be right every time. It was Sod’s law that I wrote an article saying that it was time to put Covid behind us in November just as a new variant began to sweep the world. A variant with so many mutations emerging just before Christmas wasn’t quite a black swan event, but it was more a tail risk than an inevitability. Nevertheless, the basic message that we can get on with our lives thanks to the vaccines has not been undermined by our experience with Omicron. If anything, it has been strengthened.

Putting Covid behind us doesn’t mean pretending it has gone away. There will be a next time. Presumably there will be more variants. But when the next wave comes we must follow the science of immunology and virology, not the mathematical models.

Christopher Snowdon is director of lifestyle economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs. He is also the co-host of Last Orders, spiked’s nanny-state podcast.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.