‘Nudge’ has no place in our democracy

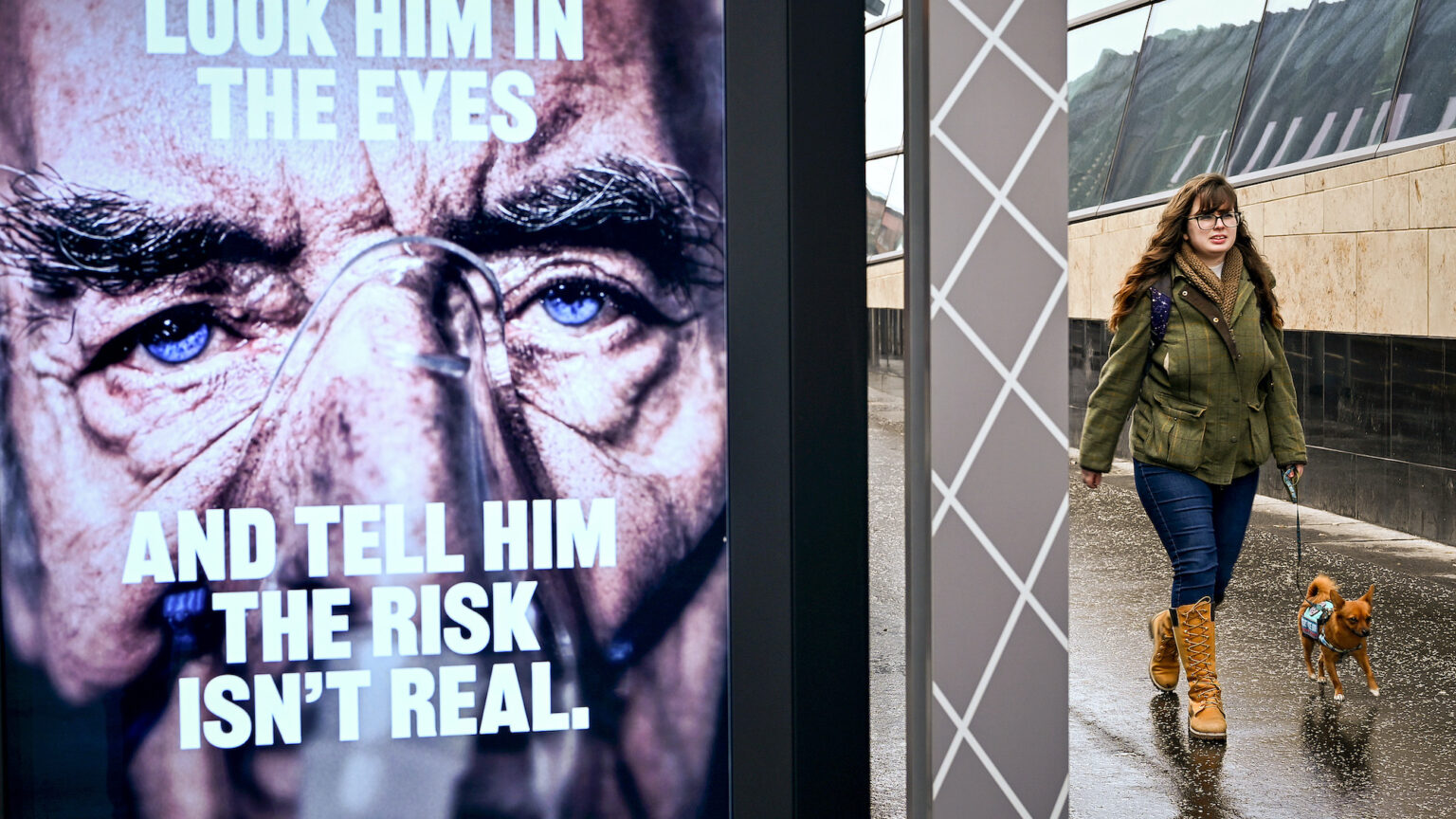

The government’s use of behavioural science violates our freedom to judge and act for ourselves.

Behavioural science, aka ‘nudging’, has been used by the government during the pandemic to scare people into doing the ‘right’ thing. This insidious development has even been acknowledged by Simon Ruda, one of the co-founders of the Behavioural Insights Team, aka the Nudge Unit, which is part-owned by the UK government. He wrote that the ‘most egregious and far-reaching mistake made in responding to the pandemic has been the level of fear willingly conveyed [to] the public’.

Though he said that the propagation of fear had more to do ‘with government communicators and the incentives of news broadcasters’ than with behavioural scientists themselves, Ruda’s admission is still striking. He even expressed concern about the state’s willingness ‘to use its heft to influence our lives without the accountability of legislative and parliamentary scrutiny’.

Ruda is not the only behavioural scientist concerned about officialdom’s systematic scaremongering. On 22 March 2020, a paper written by the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Behaviour Advisory Committee (SPI-B) for the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) complained that the public was too relaxed about the pandemic. ‘A substantial number of people still do not feel sufficiently personally threatened’, it stated, adding that too many ‘are reassured by the low death rate in their demographic group’. It then urged the government to increase ‘the perceived level of personal threat… among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging’.

Some members of SAGE have since reported feeling ’embarrassed’ by the nature of SPI-B’s advice. As one regular SAGE attendee put it last year: ‘The British people have been subjected to an unevaluated psychological experiment without being told that is what’s happening.’

It is to be welcomed that at least some behavioural scientists are now questioning the political use of their discipline. But the problem goes deeper than fear-mongering during the pandemic. We need to address the corrosive influence of behavioural science on public life in general.

And here we come to the principal problem – namely, that nudging is fundamentally anti-democratic. Behavioural scientists start from the assumption that human beings cannot be trusted to make rational choices. People’s behaviour, they conclude, should be the subject of government management. They treat people’s emotional lives, lifestyles and relationships as legitimate objects of policymaking and professional intervention.

This politics of behaviour has given rise to a new form of technocratic governance. Then prime minister David Cameron gave this technocracy its most explicit form when he helped set up the Nudge Unit in 2010. This was charged with the task of developing policies that could shape people’s thoughts, choices and actions. As far as the nudgers were concerned, subliminal psychological techniques were preferable to democratic debate and argument.

When Britain’s then deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, casually remarked in 2010 that the Nudge Unit could change the way citizens think, he spoke like a totalitarian ruler. Since when was it within a democratic government’s mandate to try to manipulate and change its citizens’ thoughts?

This elite project of remoulding the way people think and act eliminates the discursive back-and-forth that ought to characterise the relationship between citizens and their rulers. Cameron’s government was clearly aware of this implication. Back in 2010, a UK Cabinet Office and Institute for Government report, Mindspace: Influencing Behaviour through Public Policy, explains ‘that citizens may not fully realise that their behaviour is being changed – or, at least, how it is being changed. Therefore, there may be little opportunity for citizens to opt-out or choose… Any action that may reduce the “right to be wrong” is likely to be controversial.’

In some ways, Mindspace is a remarkable document. It shows that nudging depends on achieving objectives behind the back of the electorate. It therefore admits that this project necessarily deprives people of the power to democratically determine their future. The ‘Mindspace’ authors even present government action as a form of ‘surrogate willpower’. A government that substitutes its own preferences in place of people’s free will is clearly one which does not take freedom seriously. In effect, nudging allows experts to try to colonise people’s internal life, and attempt to make their decisions for them.

The aim of colonising people’s internal life has always been an integral feature of behavioural science. Decades before the term nudge was coined, behavioural psychology was seen as a key plank in social engineering. At times behavioural psychologists were so certain of their power and right to control people’s behaviour that they adopted the tone of demi-gods. In his 1921 journal article, ‘The Message of the Zeitgeist’, Stanley Hall, one of the pioneers of behavioural psychology, claimed that his discipline could solve the problems facing humanity. He said the world was sick and required a ‘great physician for its soul’. Elsewhere he wrote of the need for the ‘psychological pedagogue’ to become an ‘engineer in the domain of nature’. And he referred to the psychologist as a ‘sort of high priest of souls’.

At least today’s high priests of the soul, inhabiting the Nudge Unit and other scientific advisory bodies, sometimes acknowledge that they can get things badly wrong. However, even when they get things ‘right’ they are still violating people’s freedom to judge and act for themselves. This threatens the very pre-condition for a flourishing, democratic public life – namely, the existence of morally autonomous individuals. After all, it is only through the making of choices that people develop a sense of responsibility for themselves and for others in society.

As our experience of the pandemic shows, we need to respect the common sense of citizens and allow them to make choices in line with their circumstances. It is far better to learn from our mistakes than to be nudged into decisions by know-it-all behavioural experts. Our minds must be a no-go area for these self-appointed high priests of the soul.

Frank Furedi’s 100 Years of Identity Crisis: Culture War over Socialisation is published by De Gruyter.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.