In defence of the climate ‘bad boys’

Developing countries like India need the freedom to lift their people out of poverty.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The elephant in the room at the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow is that some of the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases are unwilling to reduce their emissions any time soon. While the UK, EU and US are all committed to getting to Net Zero emissions by 2050, and have also set themselves tough targets for 2030, countries like China, India and Russia are in no rush to follow suit.

According to the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR), in 2019 China produced 11,504 megatonnes (Mt) of CO2 emissions, more than double those of the US (5,107 Mt). India produced 2,563 Mt, dwarfing the 360 Mt produced by the UK and nearly as much as western, northern and southern Europe combined.

Critics are right to point out that this makes a mockery of attempts to reduce emissions in the richest developed countries. Global emissions are likely to carry on rising for decades, even while those committed to Net Zero impose severe restrictions on their own economies. Many are therefore calling on China and India to start cutting emissions as soon as possible.

But these emerging economies are not to blame for our own mad pursuit of Net Zero. The central focus of government policies should be the enhancement of human existence, making the world a better place for people. That means creating the conditions for economic growth. This doesn’t mean we should blindly concrete over everything. We all appreciate the beauty of nature and want to preserve it where we can. But the needs of humanity must be the bottom line. Plus, the best way to preserve nature is to get richer and make the production of food, goods and energy as efficient as possible.

It is no surprise that fast-developing countries are focused on economic growth and reducing poverty. Take India. According to the World Bank, India’s population in 2020 was 1.38 billion people – just under 18 per cent of the world’s population. Whatever India does therefore has a big impact on the world. Depending on whose data you use, India has the fifth or sixth largest economy in nominal terms – with roughly the same GDP as the UK or France. Using the alternative measure of purchasing-power parity (PPP), which takes into account how much things cost in each country, India is the third-biggest economy in the world.

The obvious point, however, is that India’s economic output is spread among vast numbers of people. Using the PPP measure again and dividing by the number of people, we get an idea of GDP per capita. According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures from April this year, the US has a GDP per capita of $68,309. Some European countries, like Denmark ($61,478) and the Netherlands ($60,461), do very well on this measure, too. The UK is a relative underperformer, with economic output of $47,089 per person.

What about the big, up-and-coming countries? China’s economy has come a long way in recent decades, but per head of population GDP is still just $18,931. It still has a lot of catching up to do. India’s position is even worse, with GDP per capita of just $7,333. Even taking into account that life is cheaper in India, economic output per person is less than one sixth of that in the UK.

While some parts of India are growing fast, there are still an awful lot of poor people. About 84million Indians live in ‘extreme poverty’ – that is, they have less than $1.90 per day to live on. And as of 2011, 60 per cent of Indians had an income less than the World Bank’s definition of ‘lower-middle income’ – a far-from-luxurious $3.20 per day. So while India has certainly made great strides in economic development in recent years, it is still overwhelmingly poor by the standards of Europe, America or Japan.

No wonder India wants to continue to expand its economic output. More and more Indians want better food, wages, transport, connectivity and air conditioning. All that requires more energy, much of which will come from fossil fuels. In its report, India Energy Outlook 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) notes that India’s energy use has doubled since 2000, but 80 per cent of that energy still comes from coal, oil and solid biomass.

India’s future energy needs are huge:

‘Over the coming years, millions of Indian households are set to buy new appliances, air-conditioning units and vehicles. India will soon become the world’s most populous country, adding the equivalent of a city the size of Los Angeles to its urban population each year. To meet growth in electricity demand over the next 20 years, India will need to add a power system the size of the EU to what it has now.’

Just three per cent of India’s current energy use comes from what the IEA calls ‘modern renewables’. However, the IEA believes a major shift is in the offing. For India, a hot country, the future is solar. Electricity production from coal is set to decline as a share of output from 70 per cent today, while solar will shoot up from four per cent, until the two converge around 2040 at about 30 per cent each. The sun will power India during the day, with coal and energy stored in batteries providing power at night. But even under this scenario, India’s overall greenhouse-gas emissions will still rise by 50 per cent by 2040.

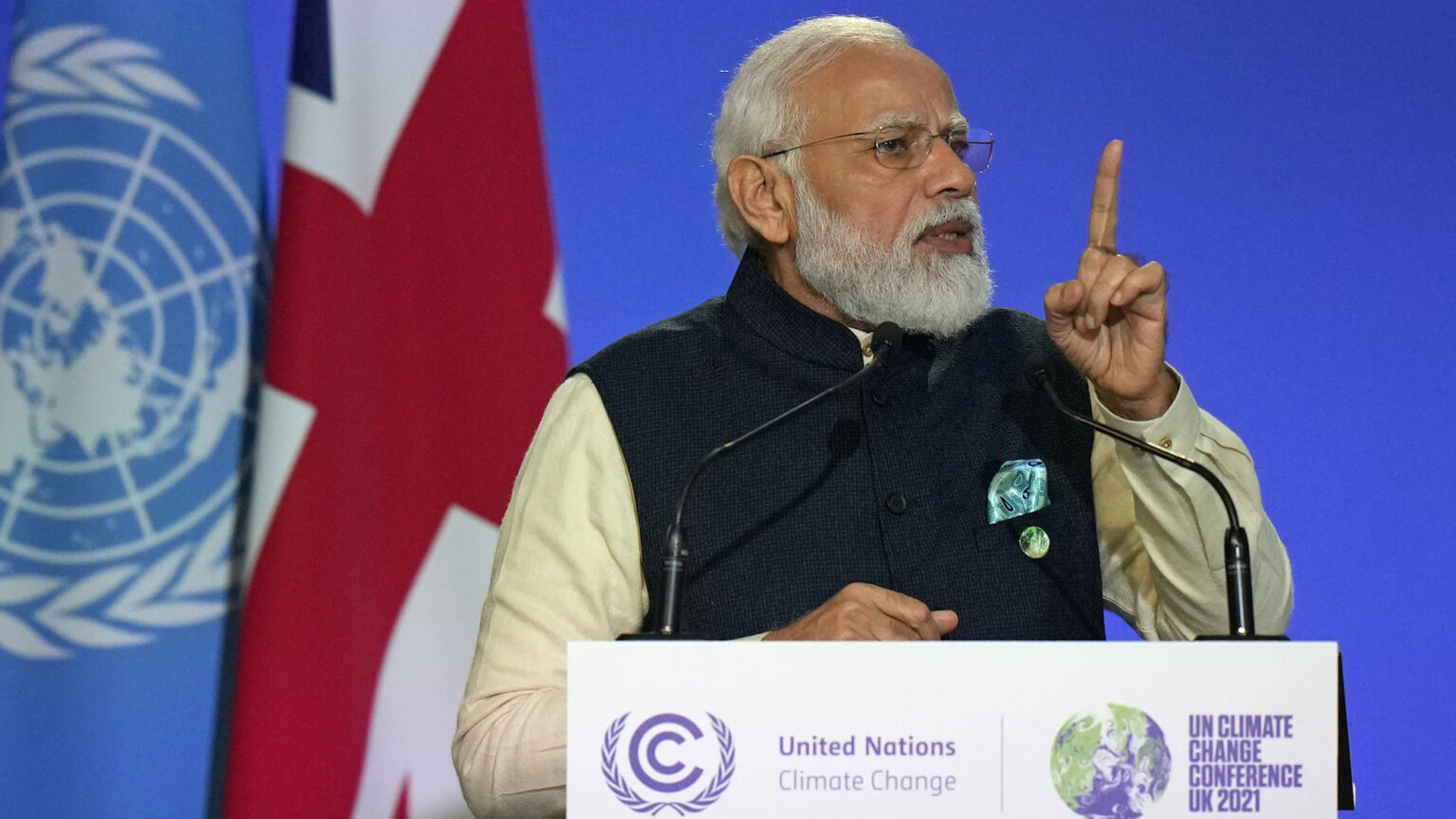

All this considered, demands that India cut emissions now are just fanciful. This week India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, committed to reaching Net Zero by 2070. Of course, 71-year-old Modi will be long gone before that target arrives. And considering that the relatively wealthy UK is well off-course for meeting its own Net Zero target, why should we expect big but poor countries like India to commit to phasing out emissions any time soon?

A warmer world will create multiple problems. But politicians pontificating about the ‘climate emergency’ and setting hopeless targets will make life for people around the world worse, not better. You cannot blame poor countries for trying to improve their citizens’ lives. A warmer world is coming whether we like it or not and we need to be ready to adapt to it. And getting richer will allow currently poor countries the flexibility and resources required to do so.

If we want to reduce carbon emissions, we need new, reliable and affordable technologies that can replace fossil fuels. Hectoring the world’s poor and demanding stringent climate targets will get us nowhere.

Rob Lyons is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.