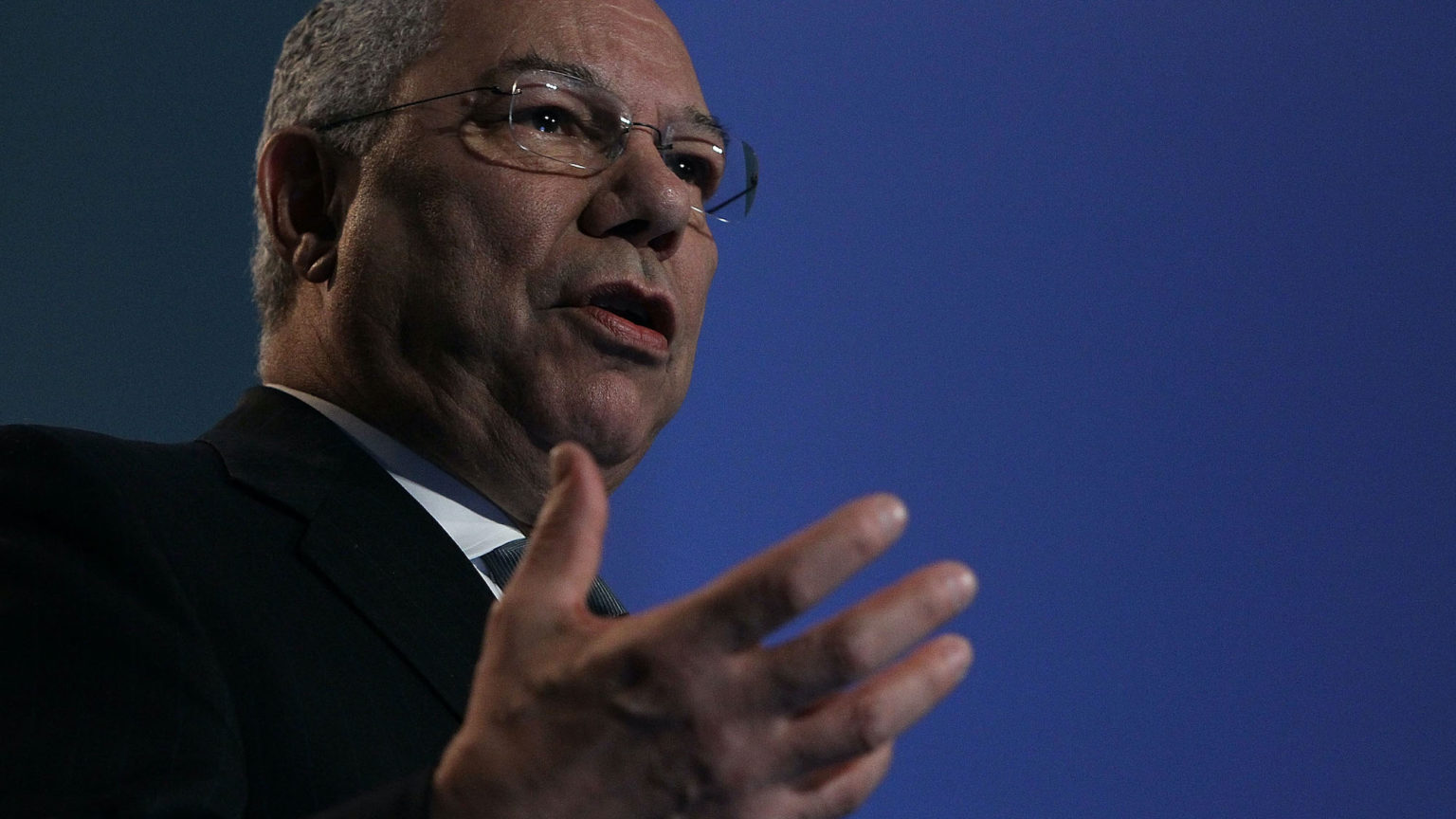

Colin Powell: the acceptable face of Western interventionism

The first Iraq war made his reputation. The second destroyed it.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The public life of Colin Powell, who died this week aged 84, will be defined by two US-led wars against Iraq. The first, the 1991 Gulf War, made his reputation. And the second, the Iraq War, arguably destroyed it.

Born in 1937 to Jamaican parents in the Bronx, Powell entered the army while still at college. He had already enjoyed a storied military career – taking in Vietnam, the fag end of the Cold War and the invasion of Panama – by the time he became the first African-American chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1989. When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, Powell was the most senior military figure in President George HW Bush’s administration. And he soon became one of the most popular, as the public face of the US-led effort to roll Iraq out of the oil-rich emirate.

The poise with which he fronted up to the television cameras to issue updates, and the ease with which his forces defeated the ramshackle Iraqi army, turned Powell into something of a celebrity. Journalists hung on his words, as if strategic pronouncements like ‘We’re going to cut [the Iraqi Army] off, and then we’re going to kill it’ were marks of military genius. Politicians, both Democratic and Republican (to whom he gravitated), sought him out as a source of proxy integrity. And, in 1993, the queen even gave him an honorary knighthood.

As one commentator put it, he was ‘the most popular American general of the 20th century after Dwight Eisenhower’. Little wonder that many thought he might emulate Eisenhower and run for president at the 1996 election.

Powell thought so, too – for a time, at least. He actually wrote two speeches in 1995, one announcing that he would run for president, the other saying he would not. In November 1995, he delivered the latter.

His political career did not end there, however. In 2001, he was named as secretary of state by another Bush, George W, and within two years he was involved in another war, once again with Iraq.

Throughout his tenure as secretary of state, Powell was perceived as a sensible, moderate, dove-ish influence on Bush. After 9/11, while vice-president Dick Cheney, secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld and a whole host of other zealous interventionists talked up the ‘global war on terror’, Powell was said to be a calmer, less sabre-rattling voice in Bush’s ear. Or as a National Security Council staff member heard Powell opine at the time, ‘I’m fighting a rearguard action against these fucking crazies’.

Yet it was precisely Powell’s public image as the sane, wise one in the post-9/11 room that was to prove so useful for the ‘crazies’. They needed someone to make the case for the war with Iraq. They needed someone with the public credibility to stand up – in this case, in front of the United Nations Security Council – and say why invading a sovereign nation, with no obvious connection to al-Qaeda or 9/11, was the right thing to do. And that man, everyone seemed to agree, was Powell. ‘You’re the most popular man in America. Do something with that popularity’, Cheney told him. Powell was said to be reluctant, but admitted that it was ‘important’ he ‘kept the job’.

And so it came to pass. On 5 February 2003, Powell, seated in the Security Council chamber, told the world that Iraqi president Saddam Hussein was in possession of weapons of mass destruction. He spoke of ‘facts’ and ‘evidence’. And he came with photographs, diagrams and CIA intercepts, ‘proving’ Hussein’s evil designs upon the world. It was fantastical stuff, of course, closer to pulpy spy fiction than the product of intelligence gathering. He even held up a vial containing a teaspoon of fake anthrax while intoning darkly that Iraq had ‘tens upon tens upon tens of thousands of teaspoons’ of the deadly pathogen.

‘There can be no doubt’, Powell concluded, ‘that Saddam Hussein has biological weapons and the capability to rapidly produce more, many more… Leaving [Iraq] in possession of weapons of mass destruction for a few more months or years is not an option, not in a post-[9/11] world.’

This was the US government’s case for war, laid out over the course of nearly two hours by its most respected public representative. It was to serve as the pretext for an invasion that first removed Saddam Hussein from power and subsequently led to a years-long war that ravaged Iraq and destabilised the Middle East. And it was all completely untrue.

Powell’s reputation never really recovered from his part in justifying the Iraq War. And he knew it. In 2011, he tried to insist to Al Jazeera that the speech was a mere ‘blot’ on his copybook. Elsewhere he was more defensive still, telling NPR, also in 2011, that ‘we all believed the intelligence’. ‘I was as disappointed as anyone’, he continued, ‘since I was the principal presenter of the case, when it turned out that so much of it was flawed’.

Powell’s credulity does not absolve him of responsibility for what happened in Iraq. He supported the invasion at the time. He really was prepared to wage war against a sovereign nation if it had what numerous other sovereign nations have – namely, weapons of mass destruction.

In many ways, Powell’s position was not too far from that of many of the war’s critics at the time. Most of them did not oppose the principle of interfering in another state’s affairs. They merely opposed its presentation. They wanted the interference to have the veneer of UN legitimacy. Indeed, they wanted what Powell desperately tried to give them that day – evidence of Hussein’s perfidy, ideally followed by a big legitimising thumbs-up for invasion from the UN.

Powell stepped down in 2004, declaring himself ‘pleased to have been part of a team that launched the global war against terror [and] liberated the Afghan and Iraqi people’. They are words that ring terribly hollow today. But his folly was not his alone. It is shared by all those who believed in the virtue of liberal interventionism – with or without evidence of WMD.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.