Why the Gillick ruling has stood the test of time

From puberty blockers to Covid vaccines, context is everything when it comes to children’s ability to consent.

Clinical consent is complicated. It’s about far more than who is allowed to sign a form. It’s about whether someone is capable of agreeing to a treatment, based on an understanding of the problem it targets, and of the risks and benefits of the treatment itself. It’s often difficult to work out how to decide if someone – anyone – understands the vagaries of how these risks apply to them. This is particularly true when it comes to people on the cusp of adulthood, but not quite there yet.

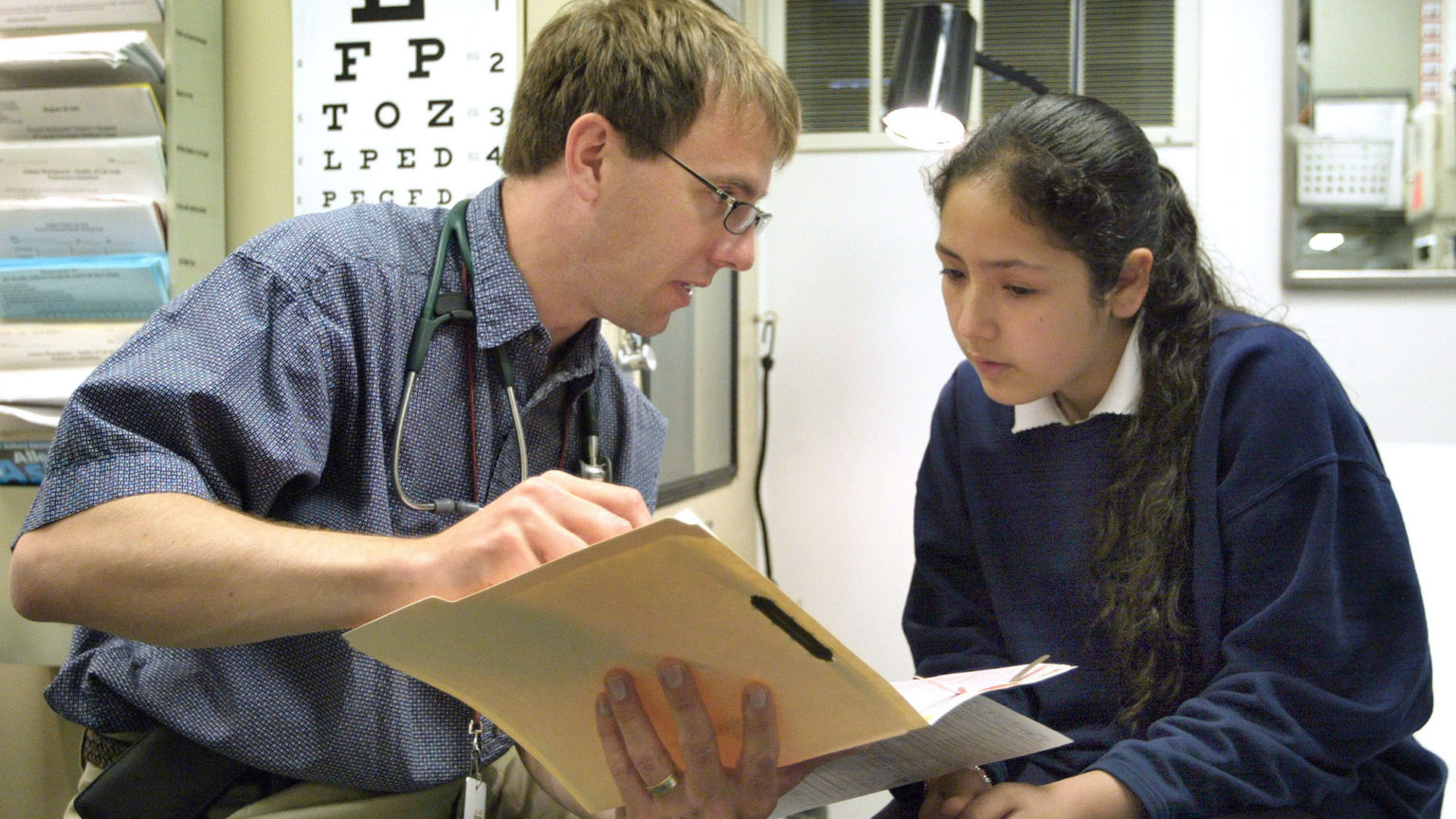

Usually, doctors are able to manage younger patients with a degree of common sense and good judgement. If a sensible 14-year-old asks his doctor to look at his crop of verrucas when his parents are at work, he is unlikely to be sent away and told to return with his mum. Most of us would probably think it ridiculous if he was. We like to see young people take responsibility for themselves and for their health. But things get complicated when treatment conflicts with the deeply held moral values of parents. A doctor can safely assume that parents want an annoying wart virus to be treated, but it’s not so clear cut when it comes to things like prescribing birth control.

Historically (and predictably), the traditional area of controversy has been around sex – especially in relation to contraception and abortion. The ‘sex thing’ was settled by the law courts almost 40 years ago. In 1983, a woman named Victoria Gillick failed to convince the High Court to prevent her daughters receiving contraception without her permission before they turned 16.

In a stark illustration of the dangers of invoking court rulings in personal disputes, Gillick managed to bring about the opposite of what she wanted. She had hoped to get doctors banned from treating minors without parental consent. Instead, when the case was eventually decided in the House of Lords, she got confirmation that a child’s decision-making capacity should be judged according to the individual’s maturity and capacity to consider the consequences. Just to rub Gillick’s nose in it further, the case led to the Fraser Guidelines, which spelt out the consent test that should be applied by doctors when prescribing contraceptives to under-16s. These guidelines have endured until today because they are sensible and proportionate.

Recently, however, the principle of Gillick competence has come under scrutiny in different areas. A veritable storm has erupted about Gillick competence being invoked when a child (in this case, anyone under 18) has a different view on getting the Covid vaccine to his or her parents. Last month, showing its typical instinct to throw fat on any parent-related fire, the Daily Mail reported, ‘Fury over plans to vaccinate children against Covid as parents demand final say “to stop youngsters being peer-pressured into inappropriate decisions”’. As evidence that ‘the controversy [had] reached boiling point’, it cited actor-turned-politician Laurence Fox, who said that he would remove his children from school if parental consent was not required for their vaccination.

Last week, the courts reasserted the principle of Gillick competence in the same week, in relation to consent to hormone treatment to delay a child’s puberty. This treatment can make it easier for a young person to adopt a gender identity that does not correspond to their sex. The Court of Appeal ruled last week that under-16s can consent to this treatment, overturning an earlier High Court ruling.

Thanks to these two controversies, suddenly all manner of people are up in arms about the Gillick ruling. Forty years ago, those who were opposed to Gillick competence were mainly conservatives campaigning for ‘traditional family values’. At the time, this was code for opposing sex outside marriage, divorce, single parenthood, homosexuality and pornography. Today, the concerns about Gillick are different. Even those who say they want to preserve family values are not talking about sex outside marriage. They are worried about the ever-expanding scope of law and regulation into home and family life – areas that have traditionally been considered private.

Personally, I am extremely sympathetic to these anxieties over the state’s role in family life. In Scotland, for instance, the state has already fixed in law exactly how children can and cannot be disciplined. It is hardly surprising, then, that parents feel their authority is being undermined.

But if the Gillick principles were to be set aside, they would leave a ridiculous mess of conflict behind them. While the legal system needs to make a clear distinction between childhood and adulthood in some areas (and the Children Act of 1989 sets it at 18 in most instances), in practice children mature at very different ages and their capacity to apply rationality and common sense varies.

The principle that our bodies are our own and that we must personally consent to interventions relating to them has underpinned our laws since medieval times. Only those who are incapable of consent should ever be excluded from this principle.

The good thing about the Gillick principles is that they accept that context is everything. When prescribing contraception, doctors weigh up whether the patient understands the risks and benefits of the method of birth control under discussion, and the patient is then treated accordingly. And despite all the hyperbole about the complexities of the Covid vaccination, it is not beyond most secondary-school children to understand what is at stake. They are capable of recognising that although they are personally at very low risk from Covid, there is a societal benefit to them being vaccinated. Besides, the documented risks of the vaccine are low.

Already, school vaccination programmes offer a three-in-one booster jab to prevent tetanus, polio and diphtheria. They also offer protection against HPV and a shot against meningitis and septicaemia. In some schools, vaccinations against flu are offered, too. All of these things are already subject to the same principles of Gillick competence that will apply to Covid vaccination. So maybe Laurence Fox and the Daily Mail need to calm down a bit. If their concern is about the Covid vaccine specifically, they should not try to muddy the waters to pretend this is about consent. If you object to the use of Gillick competency in a vaccination programme, you are protesting against a train that left the station four decades ago.

The importance of context-specific decisions is just as clear with Covid jabs as it is with puberty blockers. It is clearly vital for both children and their parents to be able to understand and appreciate the risks and long-term consequences of these treatments. Last week, the Court of Appeal returned to the principle that hard-and-fast age limits are not the best means by which to decide whether children can consent to puberty blockers. There is wisdom in that principle – and even those of us who are worried about puberty blockers can surely recognise this.

Political dogma and clinical care do not sit well together. Views will always vary depending on the treatment, the reasons for it and the capacity of the child in question to understand all of this. We may be nervous about the fact that doctors are required to use judgement rather than rubber stamp consent forms. We may worry about where their judgement will fall. But it is better than the alternative of doctors just following orders.

Ann Furedi is author of The Moral Case for Abortion. Follow her on Twitter: @AnnFuredi.

A world gone mad – with Brendan O'Neill and Julia Hartley-Brewer

Wednesday 22 September – 7pm to 8pm

Tickets are £5, but spiked supporters get in for free.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.