Occupy: a radical charade

10 years on, the utter emptiness of this movement is striking.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

On 9 June 2011, Canadian magazine Adbusters tweeted, ‘America needs its own Tahrir acampada. Imagine 20,000 people taking over Wall Street indefinitely.’

At first, few paid much attention. But by early September – thanks in part to the efforts of hacktivist collective Anonymous – Adbusters’ call to tents was starting to pick up. Adbusters then issued its defining tweet. ‘Are you ready for a Tahrir moment?’, it announced, again referencing the site of the Egyptian protests that brought down President Mubarak. ‘On 17 September, flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street.’

And that is what happened. On 17 September, thousands of protesters ‘flooded’ into Wall Street – or, as Adbusters called it, ‘the financial Gomorrah of America’. Occupy Wall Street (OWS) was born. Soon, paler imitations of OWS sprung up across America and Europe, including one, on 15 October 2011, in St Paul’s in London.

Pitched in Zuccotti Park, near Wall Street, OWS lasted for two months, during which time the occupiers spoke as ‘human microphones’, played drums and pontificated airily. It came to an end on 15 November, when New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, at the behest of Zuccotti Park’s owners, Brookfield Properties, finally sent in the NYPD to dismantle the camp.

Adbusters and no doubt many of the occupiers may have wanted to dress themselves up as heirs to the Arab Spring – at that point, in the autumn of 2011, that was still a good look. But the reference to Tahrir Square is misdirection. Occupy bore no relationship to the protests that brought down brutal dictatorships in Tunisia and Egypt. Its roots lay not in freedom struggles in the Middle East, but in the mainstream, banker-bashing response to the financial crisis of 2008 – and, before that, in the shallow anti-capitalism of the anti-globalisation movement. The ingredients for Occupy’s brand of protest were familiar even then – a mixture of resentment towards a financial elite bailed out by taxpayers, and a long-standing, New Leftish rejection of consumer capitalism – or corporate ‘brand bullies’, as Occupy attendee Naomi Klein called them in No Logo (1999).

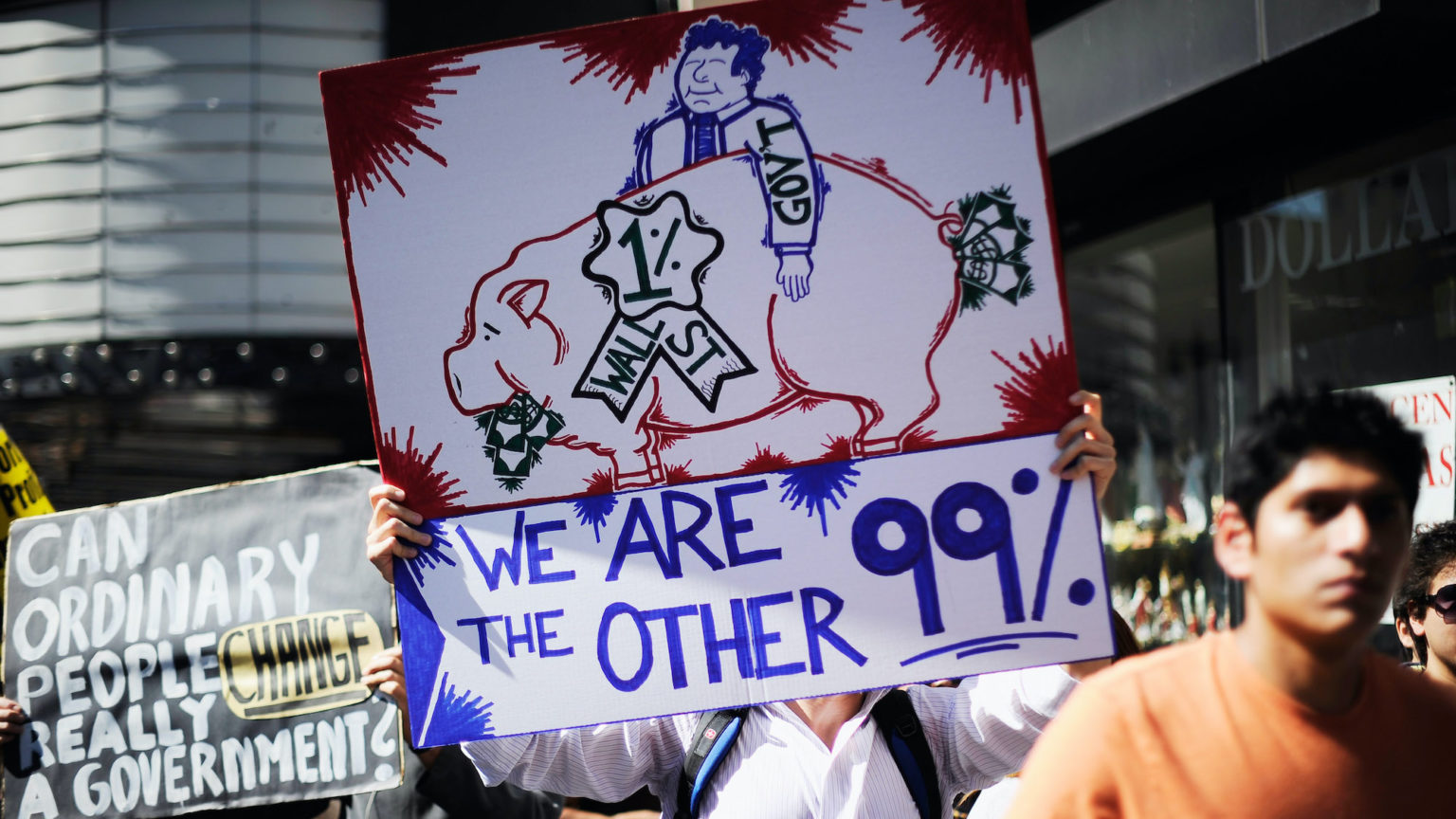

That is what is most noticeable 10 years on. The vague message emanating from Zuccotti Park and later encampments such as St Paul’s was not world-shaking. It was pre-shaken – a sloganeered echo of the sentiments espoused far and wide after the crash, with a bit of pseudo-radical reverb. ‘We are the 99 per cent’ may have been a nice line, but Occupy didn’t deepen our understanding of the financial crisis, or of the crises of capitalism.

If anything Occupy further diluted what passed for the mainstream left’s grasp of political economy. The problems of capitalism were reduced to the ‘greed’ of the ‘one per cent’, to use the terms of one prominent occupier (1). The economy wasn’t being grasped in the impersonal terms of forces and relations of production. It was being seen in the personal, moralising terms of avarice and greed. ‘We’re three years into an economic catastrophe cooked up by the people at the top’, wrote Labour activist Owen Jones in November 2011, and ‘people are [still] being made to pay for the economic crimes of the ever-powerful top one per cent’. Jones’ interpretation was common. Many others in and around Occupy also saw the financial crisis as a conspiracy ‘cooked up’ by a sinister, greedy cabal.

Virtually the entire intellectual output of the Occupy movement boils down to this combination of conspiracy theory and Manichaeism. This was not a movement that deepened our grasp of socioeconomic reality. It merely repackaged the clichés of mainstream economic and political commentary.

In real political terms, Occupy’s contribution was minimal. Not that you would think that given the endless efforts to trumpet Occupy’s impact by protesters and media cheerleaders alike. It was – as Slavoj Zizek warned it might become at the time – a movement very much in love with its own self-image. And the narcissism of its participants, performing their radicalism for weeks on end, was fed by the often fawning media coverage. It was the ‘start of a new era of protest’, announced Reuters. It had ‘rediscovered the radical imagination’, declared the Guardian. Such was Occupy’s lustre that right-on celebrities were keen to be seen down at Zuccotti Park. And, to cap it all off, in December 2011, Time magazine named the ‘protester’ as its person of the year.

The self-aggrandisement didn’t stop there. Within weeks of Occupy’s much-hyped eruption, book deals were struck, and self-aggrandising retrospectives and anthologies soon followed. Looking at these now, nine or 10 years after they first appeared, they all assert what they needed to prove – namely, that Occupy really was transformative, unprecedented, revolutionary. This Changes Everything was the title of one; The Inside Story of an Action that Changed America the title of another. One author absurdly likened Occupy’s impact to that of the fall of the Berlin Wall, while another declared that, ‘The American political landscape will never be the same again’, just as Obama was beginning the presidential campaign that would lead to his re-election.

This reality-defying hyperbole, though increasingly intermittent after 2011, has persisted down the years. Like a dodgy financial instrument, the value of Occupy is always expanding. ‘It took income inequality and corporate responsibility out of the shadows and into the streets’, declared a 2012 piece in the New York Times. A 2015 retrospective in the Atlantic claimed Occupy had ‘ignited a national and global movement calling out the ruling class of elites by connecting the dots between corporate and political power’. And a 2019 piece in Vox called it the ‘birthplace of… left-wing ideas that have gained mainstream traction’. Occupy’s legend has grown over time as the evidence for its achievements dwindles. It has changed the political discourse, re-energised the left, emboldened Bernie Sanders, etc etc. The claims keep inflating. But like all dodgy financial instruments, the real value of Occupy is negligible.

Nothing attributed to it holds up. It didn’t expose income inequality, or reveal the extent of corporate power – all of which had long been acknowledged. It merely rehearsed chattering-class pieties and platitudes, be they environmentalist or anti-consumerist.

But there is a good reason why Occupy has been so easily reimagined as a world-changing event. It wilfully signified nothing. And so it has come to signify virtually anything.

It might have begun with entirely conventional demands, for greater regulation of financial institutions and corporate lobbying. But after that, there were no demands. No leaders. And ultimately no real thought. As Brendan O’Neill wrote on spiked at the time: ‘All the negative things about the left today – the lack of big ideas, the dearth of daring leaders, the withering of organisational structures – are repackaged as positives.’

Occupy was a movement without goals. Worse still, the act of protesting was fetishised as an end in itself. Occupiers were obsessed with process – with how to debate rather than what to debate, with ‘horizontalism’ rather than leadership, with faddish theory rather than any semblance of practice.

But then, the means was always the end with Occupy. Its main objective was, well, to continue occupying, hence most of the movement’s energy was expended on legal battles with potential evictors. Some claimed that this act of occupying established a radical sense of community in the heart of our atomised, commodified cities. Occupiers, said the ever delusional Paul Mason, are ‘independent of any democratic structures and party hierarchies… living the dream of a communal, negotiated existence’.

The idea that these encampments, consisting by and large of the over-graduated and credentialed, could show cities of millions of people how to live together was insulting. This signalled the condescension of occupiers towards the 99 per cent on whose behalf they claimed to speak. But then, the populism at Occupy’s heart was always ersatz – a fact exposed by Occupy champions’ broad revulsion towards the genuine populist kick-backs against the one per cent in 2016.

In a sense, the eviction of the occupiers in Zuccotti Park in November 2011 was the best thing that could have happened to them. It gave their protest a point, a terminus. It even gave it a radical ambience, as the forces of private property asserted themselves.

Occupy St Paul’s, which dragged on for months, captured better the emptiness of this whole radical performance. After the attention stopped, and the sources of media affirmation dried up, there was little to sustain it. As journalist Laurie Penny noted forlornly in January 2012, ‘This is what the Occupy movement looks like: a network of mutual support for the lost and destitute… Even those who haven’t been living here full-time have an air of righteous exhaustion about them.’

With the benefit of 10 years’ hindsight, the whole Occupy charade has an air of righteous exhaustion about it. It now looks less like the beginning of a new era than one of the last gasps of the old one.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

(1) Occupying Wall Street: The Inside Story of an Action that Changed America, by Writers for the 99%, OR Books, p13.

A world gone mad – with Brendan O'Neill and Julia Hartley-Brewer

Wednesday 22 September – 7pm to 8pm

Tickets are £5, but spiked supporters get in for free.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.