Thank God Emma didn’t listen to the ‘mental health’ bores

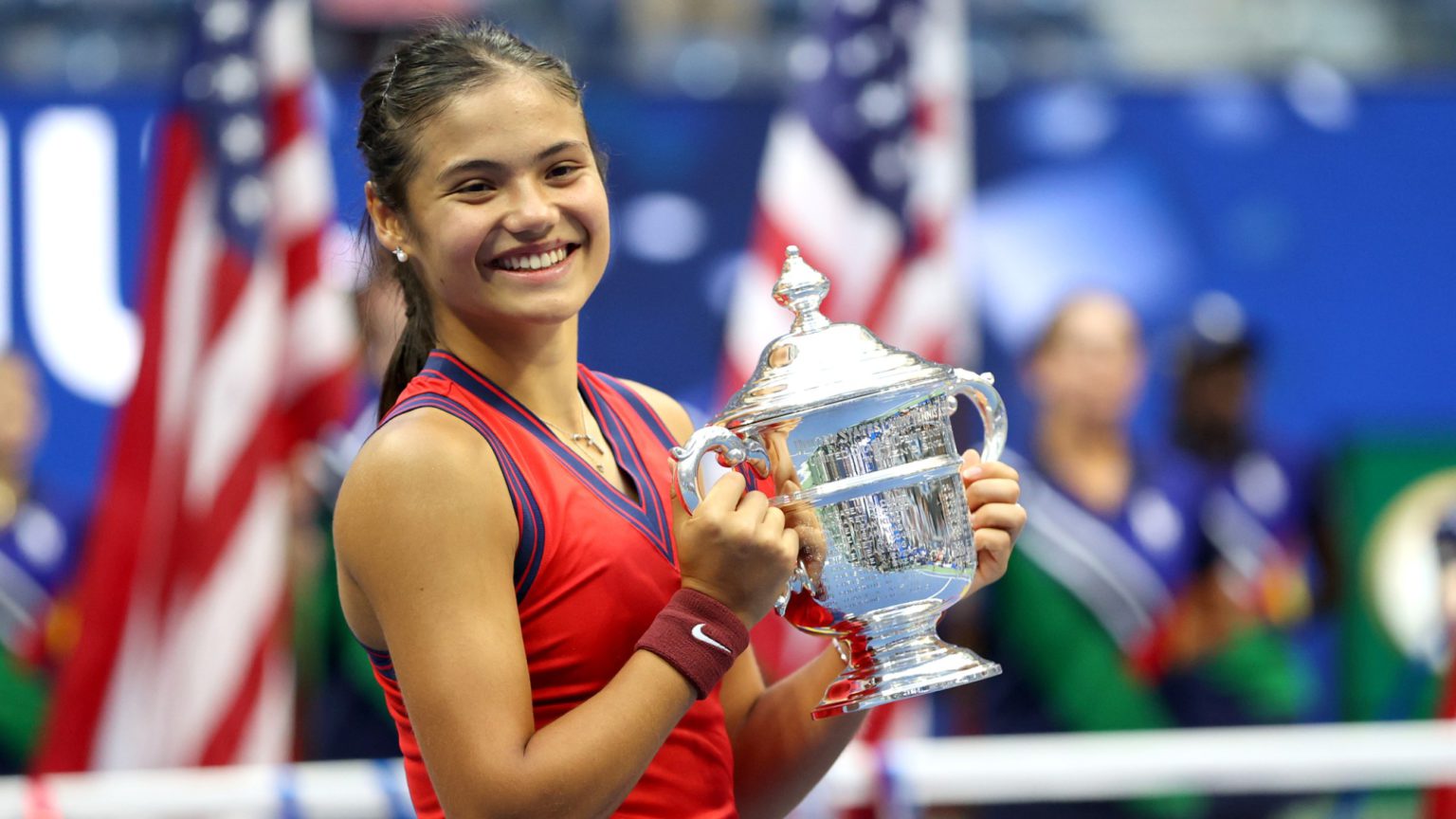

Emma Raducanu’s stunning victory in the US Open reminds us that quitting is always a bad idea.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

One of the best moments in the electrifying US Open women’s final yesterday was when the runner-up, Canada’s Leylah Fernandez, was receiving her plate. Asked about what her future holds, she said, with tears in her eyes, ‘I hope to be right back here in the finals, this time with the trophy… The right trophy.’ The right trophy. It was plain as day what she meant: she had won the wrong trophy – the second-place trophy – and it was the victor’s cup she wanted. It was that sweet taste of triumph she longed for, which she had played her guts out for. What Fernandez was really saying is that second place doesn’t count; it’s ‘wrong’; it’s winning that matters.

As everyone in the UK now knows, the winning was done by the dazzlingly talented 18-year-old Bromley girl, Emma Raducanu. She stunned the world of tennis by becoming the first qualifier in tennis history to win a Grand Slam, the youngest major tennis champ since 2004, and the first British woman to win the US Open since Virginia Wade in 1968. Not bad for someone who just nine months ago was tweeting: ‘So are A Levels happening?’ Raducanu clearly shares with Fernandez that determination to win, that deep conviction that carrying off the winner’s cup – and a cheque for $2.5million – is what counted above all else. And such steely resolve to come out on top, to focus one’s every physical and mental attribute on the seizing of the crown, is admirable in an era in which weakness is too often prized more highly than autonomy, and in which quitting is now a culturally validated response to pressure.

It could have been so different. The last time Raducanu was in the headlines was when she dropped out of Wimbledon in July. This stunning newcomer, who had got British hopes up so high, withdrew during her fourth-round clash with Ajla Tomljanovic. Seventy-five minutes into the game Raducanu went for a ‘medical timeout’, after apparently experiencing problems of breathlessness, and minutes later it was announced she would not be returning. ‘[H]er unheralded odyssey of heroics at Wimbledon 2021 was over’, as they said on the official Wimbledon website. Raducanu later clarified that she had felt overwhelmed by the whole experience and, as predictably as night follows day, there was an explosion of excitable, ridiculous commentary about how wonderful it is that young sports stars are putting their ‘mental health’ before their sporting achievements.

Raducanu was spoken of in the same breath as Naomi Osaka, who withdrew from the French Open in May, citing ‘mental health’ issues. To many of us, though, Osaka’s fleeing of the Open looked more like a cloying celeb temper tantrum dolled up as a mental-health crisis. Really, she didn’t want to speak to the media, and was fined $15,000 for refusing to do so. Later, when Simone Biles pulled out of various Olympics events, once again for alleged mental-health reasons, all three of these brilliant young athletes were celebrated as new kinds of role models. Role models who make it clear that it’s okay to feel down; it’s okay to drop out of big, scary things; it’s okay, essentially, to quit. As the executive director of UNICEF – ! – said, we now have ‘role models’ who are ‘showing the world it’s okay to prioritise your mental health’.

The gushing commentary was ceaseless. The three women were praised for sending a powerful message (albeit one about how it’s cool, apparently, to feel powerless, and to cave in to your fears). One expert said the best thing about the Osaka / Raducanu / Biles quitting frenzy was that it showed young people that it’s absolutely fine to throw in the towel when the going gets tough. He didn’t use those exact words, natch. They never do. Instead he said: ‘Seeing their heroes and icons open up gives them permission to do the same [and] increases the awareness around mental wellbeing.’ I knew things were bad when Matt Haig, writer of motivational claptrap for depressed rich people, said he felt ‘very grateful’ to these women for showing that it’s okay to take ‘time off for a mental issue’.

Of course it is okay to take time off for a mental issue. Some people suffer from serious mental ill-health and they require time, resources and sympathy in order to improve their condition. But too often today, all sorts of perfectly normal experiences are being redefined as mental-health problems. Exam stress, occasionally feeling anxious, being a bit hyperactive, feeling happy one day and not so happy the next (hello, life!), and, now, feeling the strain of competing in a tennis Grand Slam or at the Olympics – all these things have been pathologised, transformed into mental ailments on a par with, oh I don’t know, schizophrenia. People now actively seek out a mental-illness diagnosis. It’s this season’s must-have. You’re nobody without a bipolar disorder. I’ve lost count of the number of young people who’ve told me they suffer from mental ill-health while I hope and pray they can’t hear the scepticism lurking behind my feigned expressions of sympathy.

The problem with all this pathologisation is that it convinces people – young people in particular – that they can’t cope with life. That it’s cool, in fact, not to be able to cope with life. And nothing’s your fault. It’s not your fault you did badly in your exams. It isn’t because you spent your revision time watching twentysomething virgins play computer games on Twitch. It’s because you suffer from exam anxiety, duh. It’s not your fault you can’t hold down a relationship or advance in your career. It’s because you suffer from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Every personal failing can be papered over with a doctor’s note. This is so destructive and fatalistic; it actively distracts people’s attention from the question of how they might turn their lives around through hard work and bravery and instead whispers in their ear: ‘Listen, are you sure you’re not just mentally ill?’

It is especially destructive in the world of professional sport. Sport is meant to be stressful. That’s the entire point. This is a sphere of life in which you must push yourself to your physical and mental limits, face down your demons, walk tall on to the gym floor or the track or the court, and do something superhuman, something the rest of us cannot do. To pathologise stress in sport is to pathologise sport itself. To sing the praises of quitting – which is essentially what Osaka, Biles and Raducanu did – is to tear the heart and lungs out of sport and denude it of its raison d’être. This is what is so extra admirable about Raducanu’s victory in the US Open – she clearly decided to take a different path to her Wimbledon one, to become a different kind of ‘role model’. Not the kind that says ‘Quitting is fine!’, but the kind that says ‘Winning is sweet. Winning is everything.’

If Raducanu had listened to the self-styled mental-health gurus who clog up the worlds of commentary and expertise, she might never have discovered in herself the qualities of grit and drive that are necessary to do something as spectacular as win the US Open. But she didn’t listen to them, it seems. Rather, as a BBC report says, she pushed herself hard. As one of her former coaches put it, ‘Her demand of herself and her demand of her team has… been something incredible’. If Raducanu had not conjured up her inner resources, and instead had let the mental-health industry convince her that real role models advertise their weaknesses rather than ruthlessly cultivating their strengths, she might have been deprived of that trophy, and we might have been deprived of a brilliant new British champion.

People are already talking about the ‘Raducanu Effect’ – how Emma might inspire young girls in particular to pick up a racquet, or something else, and get stuck into sport. I hope this effect is real. And I hope its most important message – that perseverance is preferable to quitting, that facing down your fears is better than capitulating to them – cuts through. Raducanu should be cheered not only for beating Fernandez and smashing various records, but also for, implicitly at least, taking a stand against the real stress of our age – the stress on us all to admit we are wimps rather than try to be something better than that.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked and host of the spiked podcast, The Brendan O’Neill Show. Subscribe to the podcast here. And find Brendan on Instagram: @burntoakboy

A world gone mad – with Brendan O'Neill and Julia Hartley-Brewer

Wednesday 22 September – 7pm to 8pm

Tickets are £5, but spiked supporters get in for free.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.