Will we ever put children first?

Children could face a third year of disrupted education if we don’t stand up for them.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Lockdown and school closures have had an appalling impact on children. At the weekend, the Local Government Association warned of a ‘harrowing’ rise in child abuse. Serious incidents of abuse and neglect rose by a fifth between April 2020 and March 2021. During that year, 223 children died from abuse or neglect, and a further 284 were victims of serious harm.

This is indeed harrowing. What is perhaps more upsetting still is that interim data, published in January, during the second round of school closures, was already showing a rise in suspected abuse following the first lockdown. We understood perfectly well how much harm school closures were doing, and yet we kept them closed anyway.

There is no doubt that our Covid response has caused considerable harm to children and young people. Over the past 18 months, pandemic policies have taken a wrecking ball to children’s education as well as to their mental and physical health. In some cases, as the abuse statistics show, children have even tragically lost their lives as a result.

It is estimated that more than a billion teaching days were lost during the pandemic. The average pupil in the last school year spent more school days at home than at school. One in four young people reported feeling ‘unable to cope with life’ after the first lockdown. A third failed to do just 30 minutes of physical exercise a day. Close to 100,000 children were marked as persistently absent during the last school year. The attainment gap between privately educated children and children in state schools has grown even wider.

Even when schools were open, education was still being disrupted. Towards the end of the most recent school term, around one million children were in forced isolation – though only 47,000 of them had tested positive for Covid.

You might have thought that with the benefit of this painfully acquired hindsight, and after a year and a half of penalising children, society would finally be ready to put children first. You would be wrong.

Children and young people are now facing a third academic year of disruption. Universities have warned that they do not plan to resume full face-to-face teaching. The government is considering vaccine passports for further-education colleges to exclude unjabbed students. And in schools, the start of the next term could be delayed in order to allow for healthy pupils to be tested. The educational landscape is a long way from normal.

Worse, these things are almost certainly a sign of more to come. Last week, the Department for Education updated its guidance for schools. On the surface, it is an improvement on previous guidance. The default measures are now limited to what looks to be a sensible list – good hygiene for staff and pupils, more cleaning of classrooms, better ventilation and, of course, isolation for sick children.

The trouble is that the guidance for schools is full of break clauses. If cases start to emerge in schools, school leaders are able to pull an emergency rip cord. For instance, they will be allowed to re-establish the ‘bubble’ system in certain circumstances. That means sending whole classes and year groups home after just one pupil tests positive for Covid. We could end up returning to a system in which healthy children are once again left isolated at home – even though we know what harm this will do to children. It’s not clear if there is any benefit in this for adults, either, when more than nine in 10 currently have Covid antibodies.

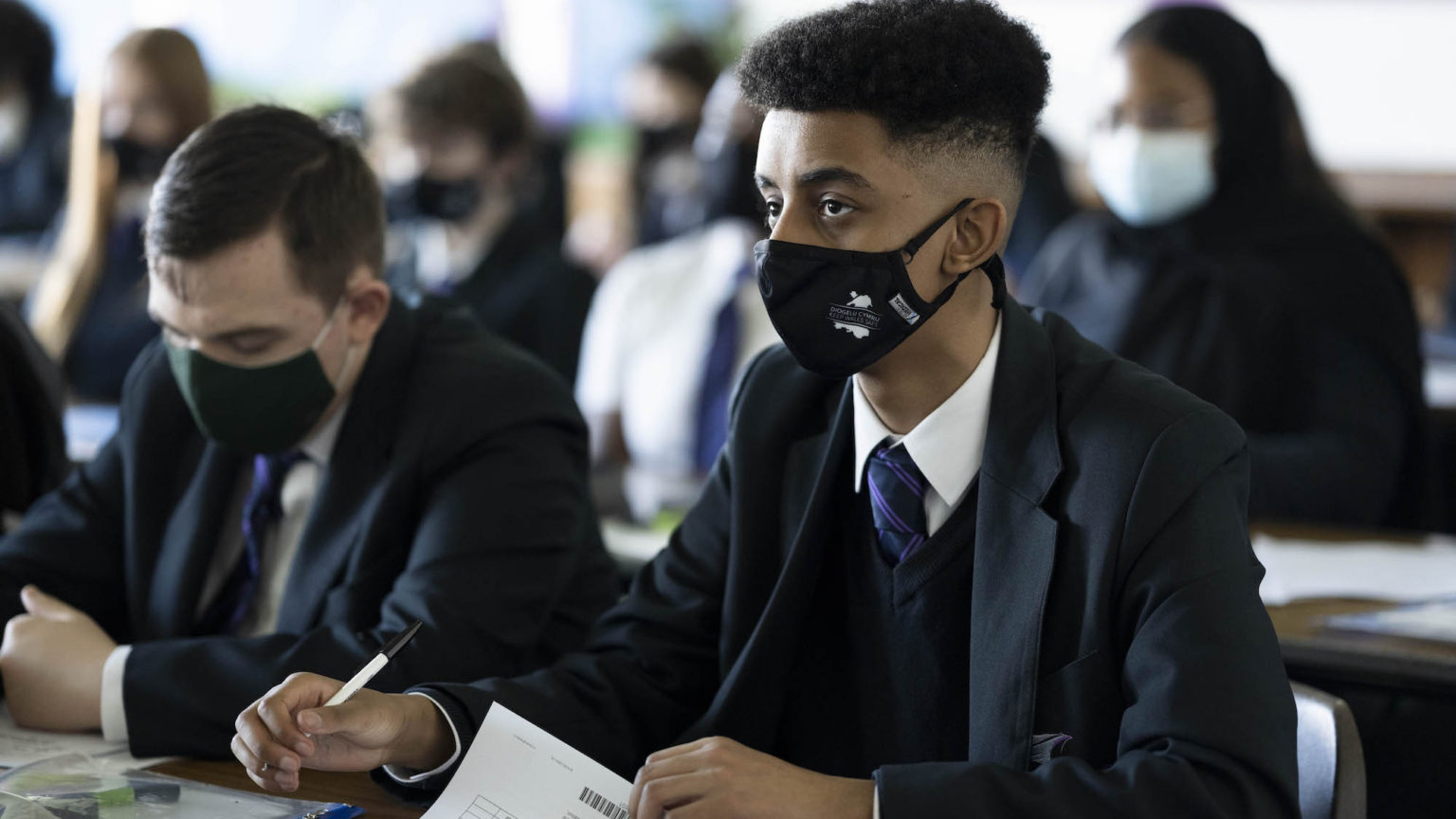

Yet for the teaching unions, this guidance does not go nearly far enough. The National Education Union has called for schools to reintroduce ‘bubbles’ if a school finds just two Covid cases. According to a poll of teaching staff reported in The Sunday Times, nearly one in five schools is planning to stagger the start or end of the school day throughout next term, and one in eight secondary schools will insist on masks in class. In other words, school is not going back to normal.

There is a lot of uncertainty as to whether these control measures have done much to prevent the spread of Covid in schools. We do know for certain, however, that these measures have caused enormous harm to children’s education and welfare. And yet, here we are, once again, planning to disrupt children’s lives all over again.

Molly Kingsley is one of the founders of the parents campaign group, UsforThem.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.