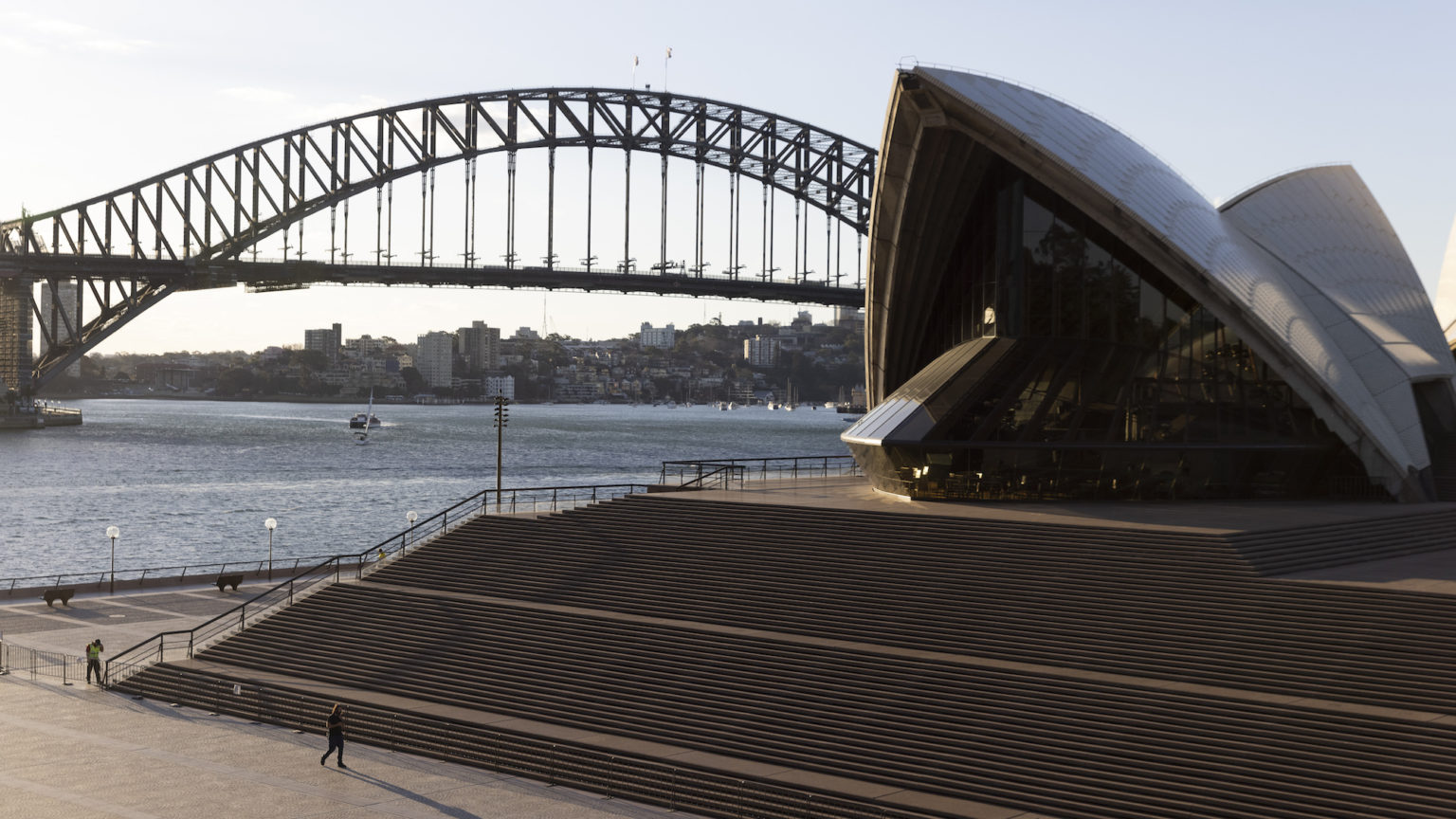

Australia is paralysed by fear

The land of Crocodile Dundee wants to hide under the blanket forever.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Inserting a word like ‘only’ before the number of coronavirus deaths has become a mark of callousness in this sentimental age. Yet the coronavirus death toll in Australia demands to be put into perspective given the draconian restrictions to economic and social life now in force.

There have been around 30 deaths in Australia since cases began to rise at the start of July. In Britain, around 2,000 people died of Covid-19 in that same period, but Britons have not been incarcerated in their own homes and the army is not manning border checkpoints between Surrey and Kent.

The meek acceptance of some of the harshest lockdowns in the world in the land of Crocodile Dundee cries out for an explanation. Why do the Brits have the courage to wander around freely after recording 188,000 positive tests in a week? Why aren’t they being kept at home for their own safety? Why aren’t their movements controlled by a list of regulations 27 pages long, as they are in Melbourne after a mere 50 locally acquired cases were discovered in the same period? Why is it okay for Brits to stand maskless to order two pints of lager and a packet of crisps when the picnic police are fining people in Sydney a thousand bucks for the crime of eating a sandwich in the park?

Since the odds of having caught the virus in Australia so far is tiny, as are the chances of it killing healthy people under the age of 70, one would have thought Australians would have collectively told the public-health nags to pull their bloody heads in. Not so. Many people want them to go harder. The premier of New South Wales, Gladys Berejiklian, for instance, is constantly badgered at her press conferences for being too soft, for not locking down harder and sooner, and for not extending the indoor mask rule to everywhere outside the home.

The simple explanation is that Australians are behaving this way because most are scared witless. The July edition of Ipsos’s regular report, What Worries the World, found that Australians fret about Covid more than people in 25 of the 28 countries surveyed.

Australia’s good fortune in controlling the spread of earlier Covid-19 variants is rapidly becoming a curse with the arrival of the far more infectious Delta variant. One reason for its early success was the prompt closure of external borders and a dogged commitment to keep them that way. The number of passengers on inbound international flights has been restricted for 16 months, making it devilishly difficult for Australian citizens to come home, let alone for others to visit. The compulsory-detention rule used to apply only to those arriving without a visa. In a grim irony, today everyone is arrested the moment they step off the plane, frog-marched on to a bus by armed police, driven to a quarantine hotel with a police motorcycle escort and forbidden from stepping out of their room for a fortnight. In the spirit of the Magna Carta, no one is exempt. As I write, our 28th prime minister is incarcerated in a 4.5 star tourist hotel that has seen better days following his return from official duties in London and India.

In addition to lockable borders and first-class universal healthcare, Australia possesses a greater strength that has, regretfully, been largely untapped: a tolerant, liberal democracy where the rules are willingly obeyed by consent, not coercion. Australia’s strong social fabric and spirit of volunteerism – usually manifested in networks of community institutions like surf life-saving clubs, ‘flying doctors’ and rural fire brigades – has not been called on to help.

Instead, the instruments of public-health compliance are the police, supplemented by the army, and so-called ‘authorised officers’ – petty officials with extraordinary powers who can order you to stand in line, or board a bus, and can even compel you to enter a hotel room where your alcohol consumption will be monitored and restricted for the next 14 days.

There must have been a saner, more reasonable approach we could have adopted – one that wasn’t built on the nutty idea that Australia and New Zealand could eliminate the coronavirus altogether, and then use magical powers to keep it out. Reason, however, has been an ineffective weapon in responding to the many public-policy absurdities that have perplexed us since coronavirus entered our lives. Policy is largely being driven by the heart, not the head. Our response to the pandemic is sentimental, and the predominant emotion is fear. Combine that with the modern culture of safetyism and you end up with a real conundrum. How can we come out from under the blanket knowing there is a risk that someone might get sick and die? How can we ensure we’re safe against every known danger, let alone those we might not even know about? Every granny’s life is sacred after all.

The deification of chief government health officers, who have risen from obscurity to become minor celebrities, has been one of the biggest mistakes so far. It has allowed politicians to outsource responsibility and avoid doing a key part of their job, which is to decide the proper balance between competing policy imperatives and to test their judgement in parliament. Instead, the authority of parliament and a thousand years of history that lies behind it has been usurped by ‘The Science’. It is an odd kind of ‘science’ that denies us the right to dispute its findings, that ignores discordant evidence, that remains rigid in the face of new facts, that keeps its data close to its chest and that cancels dissenting voices. In other words, it is not science at all. It is a form of superstition.

It is as if the world has been gripped by a kind of trembling disease, an epidemic of twitching like the one that swept through European schools in the late 19th century. We are fighting not one, but two pandemics, as Niall Ferguson observes in Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe. There is a contagion of the body and a contagion of the mind, spreading with equal rapidity on two social networks, one physical and one virtual. Coronavirus is an unwelcome visitor to be sure, but the severity of the measures and the costs incurred – both financial and human – can hardly be said to be proportionate to the risk anymore.

With hindsight, the die was cast early last year by the extravagant modelling that wildly overstated the deadliness of what we then called the novel coronavirus. The fear that escaped from the Imperial College laboratory back then has proved resistant to new evidence. The political class was infected all at once by the early, extravagant assumptions, and the media were using their licence to exaggerate still further – because that’s what the media do.

Fear has been amplified in a feedback loop, circling back to the public where it has become entrenched, altering judgements of reality. In early June, when this year’s death toll in Australia was precisely one, a survey asked people to mark on a sliding scale the number of people who they thought had died. The average response was 256.

We’ve got to get out of this place, but agreeing on a plan is hard. Australia’s peculiar constitutional arrangement requires consensus on public-health matters between six state and two territory governments, which are responsible for health, and the Commonwealth government, which controls the external borders and writes the cheques. It’s complicated.

The plan currently relies on jabs as the threshold for safety, but even at the current rate of 250,000 a day, we’ll be well into the Australian summer before the 80 per cent target is met. The truth, hardly spoken, is that even before the arrival of vaccines, many fewer Australians were likely to end up in hospital or to die from coronavirus than at the start of the pandemic. Improved medical knowledge, safety procedures at nursing homes and the decency of the Australian population, most of whom can be trusted most of the time to do the right thing, has achieved far more than the Wuhan-style command and control measures we have come to think of as normal.

The vaccines will further mitigate the risk, but as the British data demonstrate, they will not eliminate risk completely. So what next? Let us pray for the speedy development of a vaccine against fear and a booster shot of courage.

Nick Cater is executive director of Menzies Research Centre and a columnist with the Australian.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.