Henry Dimbleby is right about one thing

Talk of a ‘childhood obesity epidemic’ is based on dodgy data.

Henry Dimbleby has taken some flak for his National Food Strategy report, which calls for taxes on sugar and salt in the aftermath of the deepest recession in 300 years and when inflation is already rising. Some people have unkindly portrayed this as one overweight, Oxford-educated Etonian telling another overweight, Oxford-educated Etonian to make the poor pay more for food. Others have noted that Leon, the fast-food chain founded by Mr Dimbleby, is a major purveyor of salty, fatty and sugary products. His idea of getting GPs to prescribe fruit and vegetables has been mocked as preposterous.

Reader, I confess that I have been party to this mockery, but I come here today not to bury Mr Dimbleby but to praise one small aspect of his report. Tucked away in Appendix 19 on page 277 is the first official recognition of a problem that I have been banging on about for some time. This brief chapter begins by mentioning the dog that doesn’t bark in the report, the mantra of Public Health England, the statistic that never dies:

‘Eagle-eyed observers may notice that nowhere in this report do we use one of the most commonly quoted statistics on obesity in the UK: “One in 10 children is obese when they start primary school, and one in five is obese by the time they leave, aged 11.”’

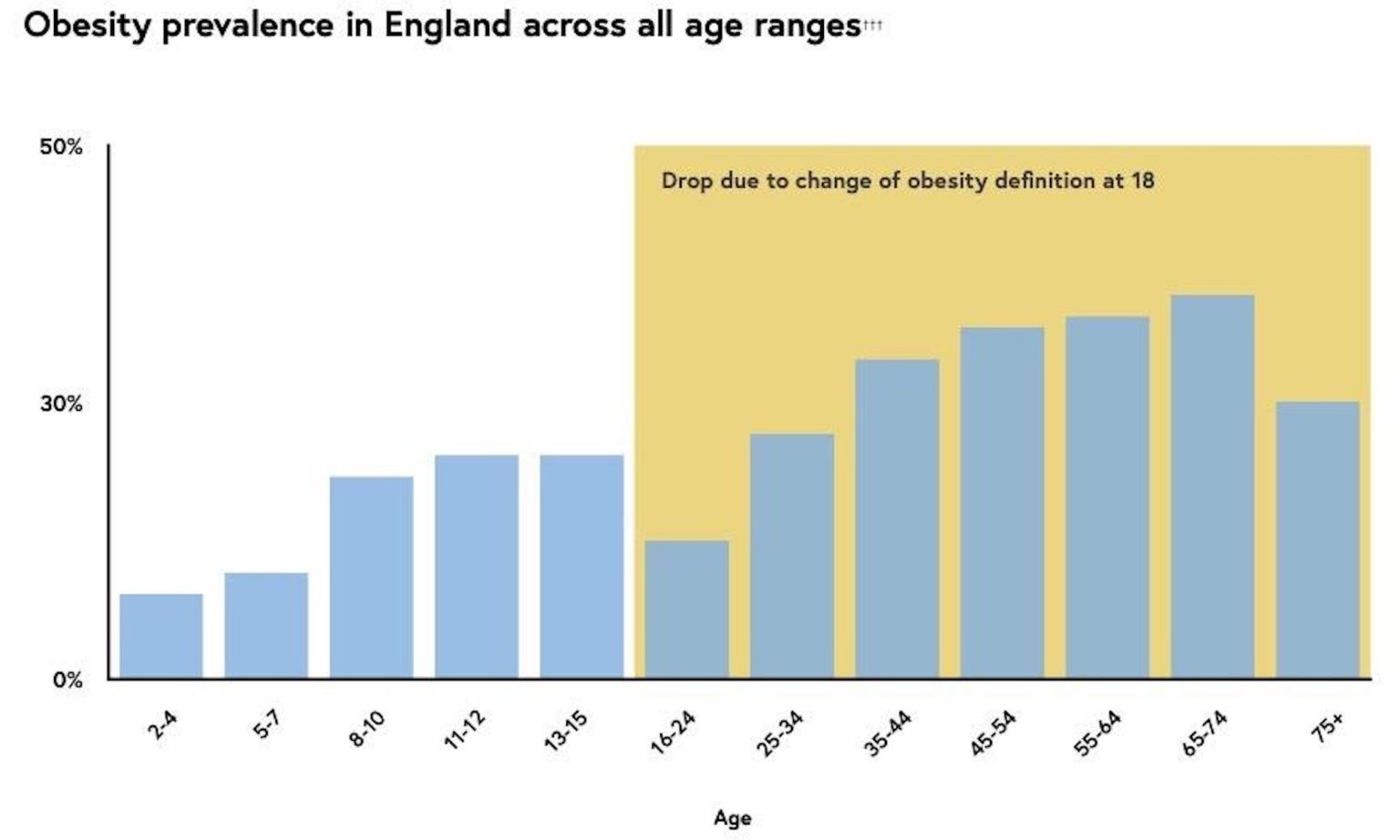

In case these numbers don’t seem big and scary enough, campaigners often add in the overweight to claim that one in three kids leaving primary school is too fat. They get fatter still in secondary school and yet, according to official figures, most of them magically become slim again when they leave.

In 2019, 27 per cent of 11- to 15-year-old males were officially classed as obese, but only 13 per cent of 16- to 24-year-old males were obese. This is not a generational effect. Every year produces similarly baffling results. Since obesity tends to increase with age, Mr Dimbleby admits that this is ‘very strange’:

‘How are our 16-year-olds performing this miraculous feat of weight loss? It doesn’t make sense, either intuitively or scientifically. The answer is, they don’t lose the weight. It’s just a quirk of data definition.’

‘Quirk’ is putting it mildly. The methodology is absolutely indefensible. It produces more false positives than true positives and allows campaigners to make claims about a childhood obesity epidemic which anyone with a working pair of eyeballs can see does not exist.

The reason for the anomaly is slightly complicated (I explain it in more detail here), but the bottom line is that none of the children in these surveys has ever been examined by a medic to get a clinical diagnosis of obesity. Schools simply weigh and measure their pupils and send the data off to the authorities who arbitrarily mark them down as obese if their body mass index (BMI) would have put them in the top five per cent of the BMI distribution in the 1980s – ie, above the 95th percentile.

The problem is that five per cent of children were not obese in the 1980s. Not even close. Only one per cent of 18-year-olds were obese at that time.

Adult obesity statistics are fairly reliable. Notwithstanding the inevitably subjective nature of defining obesity, a BMI of 30 or over makes it very likely that the person is fat. Obesity is obviously a visible condition. If you saw a clinically obese adult, you would be able to tell. But in the case of most ‘clinically obese’ children, you would not be able to tell – because they are not fat.

As Dimbleby explains:

‘The guidelines for measuring BMI in children are based on 1990 measurements of the BMI of children of all ages – known as the UK90. For reasons that are very far from clear, it was decided that, from the ages of 0-15, the BMI threshold for obesity should be pegged to the BMI of the heaviest five per cent of each age group in the UK90 data.

‘Once children reach the age of 16, the way obesity is measured abruptly changes – to the adult definition of a BMI above 30. This is a much higher threshold: only around two per cent of 16-year-olds had a BMI above 30 in the UK90 data. Overnight, therefore, a whole load of children who qualified as obese the day before their birthday become, statistically, merely overweight.’

In clinical practice, nobody uses the 95th percentile. It has never had any scientific validity. Nobody has ever been able to explain why it was chosen. It is possible that we simply copied the US, where a childhood obesity rate of five per cent in the 1980s was more plausible.

Clinicians use the 98th percentile as the cut-off. The international definition of childhood obesity uses the 98th percentile. If you look at the growth curves used by doctors to diagnose childhood obesity, the 95th percentile isn’t even on it. It is a scientific irrelevance.

The 95th percentile is only used in the UK when we gather national statistics, but those are the statistics that drive the policy debate around childhood obesity and, indirectly, food policy.

Every now and again, an outraged parent will contact a newspaper about the letter they received from school telling them that their perfectly slim child is obese or is the verge of obesity or is heavily overweight (the terminology varies). They usually assume it is a computer error. It is not. They are just the tip of the iceberg of mass over-diagnosis.

Mr Dimbleby concludes that ‘the way this statistic is measured is problematic and probably worth rethinking’. The government could slash the rate of childhood obesity overnight if it started measuring it properly, but of all the recommendations in Dimbleby’s report, I bet this is the only one that is never seriously considered.

Christopher Snowdon is director of lifestyle economics at the Institute of Economic Affairs. He is also the co-host of Last Orders, spiked’s nanny-state podcast.

Picture by: YouTube.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.