History shows us why vaccines must be voluntary

Victorian vaccination campaigns became a tool of social control – and generated a fierce backlash.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The history of vaccination is one of an heroic effort to rid humanity of deadly and blighting disease. Vaccination has scored rightly celebrated successes against smallpox, polio, tuberculosis, diphtheria, mumps, measles, yellow fever and many other illnesses.

Deliberately infecting people to promote immunity has centuries-old antecedents, but the recorded history in England begins with Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Having witnessed the practice in her travels, in 1718, she got a local nurse to put matter from smallpox sores into cuts in her son’s skin – ‘variolation’ – which gave him a mild version of the disease, followed by immunity. Variolation did carry a risk of contracting full-blown smallpox, however. George Washington’s Continental Army had an advantage over the British in 1776, because his soldiers had been variolated – even though the death rate for the treatment at the time was 12 per cent (1).

Happily, variolation was superseded by Edward Jenner’s 1796 treatment of infecting people with cowpox which, being related to the smallpox virus, promoted immunity against smallpox without the same risk. Variolation was then banned in 1840. The word vaccination comes from the Latin for cow (vacca) because of Jenner’s substitution of cowpox for smallpox. But it has, by association, come to describe all medical stimulation of immunity.

In 1978, Ali Maow Maalin, a cook who lived just south of Mogadishu, recovered from the last ever recorded case of smallpox. Worldwide, 300million people died of smallpox in the 20th century. In Britain, the peak years for smallpox were in the 19th century – there were years when as many as one in every thousand people in England died from it. The vaccination programmes adopted by governments, with the support of the World Health Organisation, have successfully eradicated smallpox and have curbed many other deadly and blighting diseases.

It may be surprising, then, that the British government’s vaccination programmes were met with widespread opposition and militant demonstrations. In Dewsbury, in 1880, an effigy of a vaccination officer was thrown from a platform into a crowd of 10,000 and torn to pieces. Five years later, as many as 100,000 marched against vaccination in Leicester, parading infant-sized coffins, with people dressed as doctors riding cows. An effigy of Edward Jenner was symbolically hanged and then thrown to the crowd (before the police retrieved it).

In 1875, seven men were elected as Poor Law guardians in Keighley as anti-vaccinators. The following year, the men were sentenced to prison, but the wagon carrying them to jail was surrounded by a crowd who beat up the police and prison officers, forcing the men’s release – though they later surrendered and were imprisoned for a month (2).

The intensity of the protests against vaccinations may seem hard to comprehend. For many years Whiggish histories celebrated the growth of public medicine as an unqualified advance. The end of smallpox was indeed an advance, but there were some other things going on in the process.

Popular hostility towards vaccination was coloured by scepticism about the new public-health policies and the revolution in government that they were associated with. The government’s willingness to intervene so directly in the organisation of people’s lives was a departure from the older, laissez-faire policy of leaving citizens to sort out their own arrangements. The policy was called the ‘new liberalism’ (to differentiate it from the ‘old liberalism’). The ‘new liberals’ were reformers, who believed in the power of reason, allied with social research and scientific expertise, to use the powers of government to solve social problems. Unfortunately, they mixed up a lot of unconscious prejudices, mostly about the poor, with their rational approaches.

Reformers like statistician and civil servant Edwin Chadwick, chief medical officer John Simon and educationalist James Kay-Shuttleworth began great works of slum clearance, digging sewers and building schools. But just as they addressed social problems, they tended to think that the real problem was the poor themselves.

If you walk around New Oxford Street or Trafalgar Square today, those broad and handsome streets were built to clear slums. But until 1900, slum clearances went ahead without new homes being built for those evicted (3). Board Schools – the first state schools – were celebrated as a great advance for the less well off, but at the time their point was to dominate and control working people.

Health programmes, too, were often mixed up with a coercive intent. Around the same time that the government was passing laws on vaccination, it passed the Contagious Diseases Act (1864). The aim was to stop the spread of venereal disease among sailors in port towns. The Act created powers that oppressed women, subjecting them to arbitrary arrest and detention in locked hospital wards. The only evidence needed was police suspicion of prostitution (4).

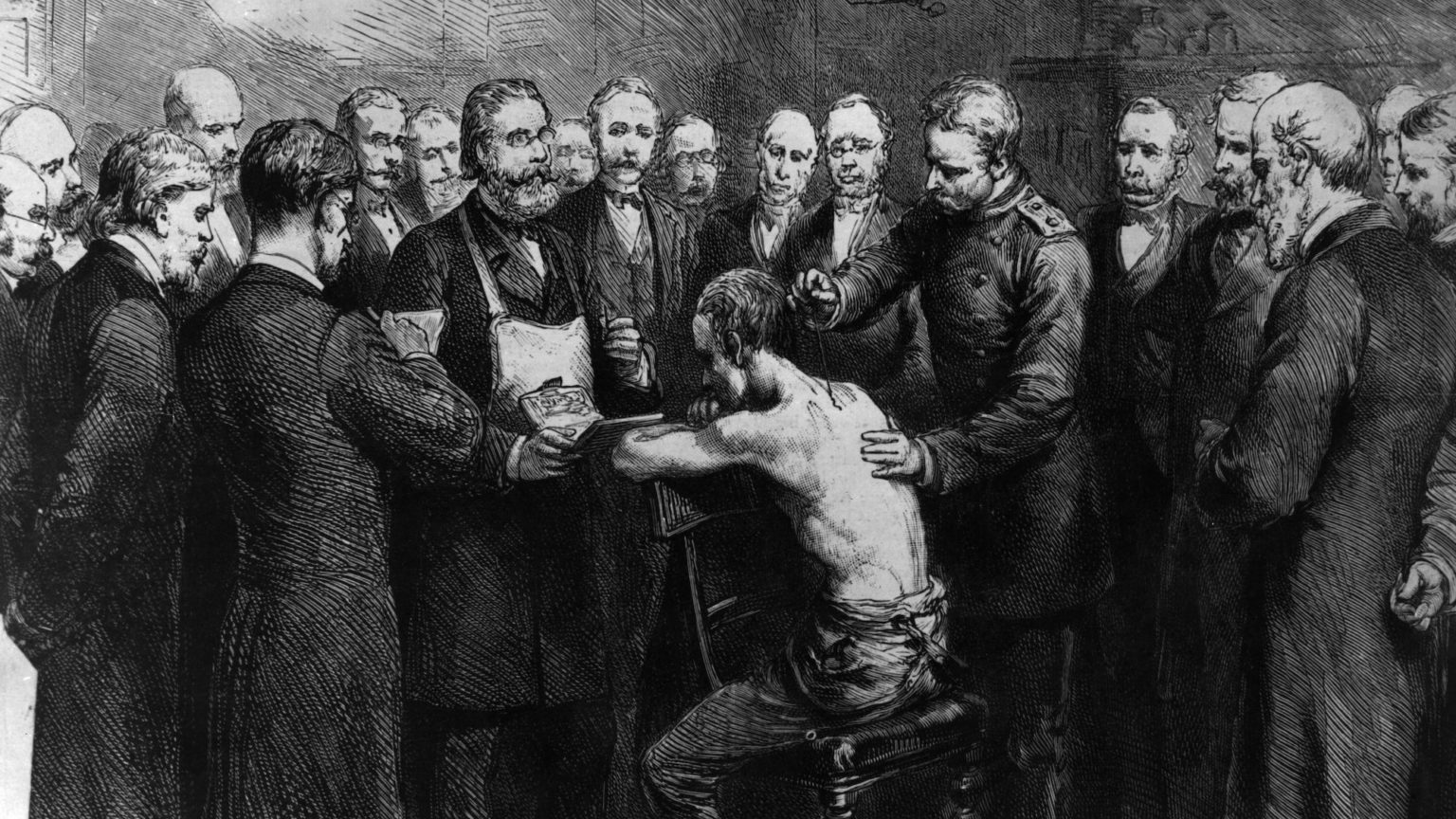

The Vaccination Act 1853 made vaccination compulsory for the first time. But it was seen as lacking powers or resources. Later Acts in 1867 and 1871 created vaccination officers and offences with fines or imprisonment. They also made it obligatory to vaccinate newborn infants. Though vaccination advocates like Sir John Simon and the British Medical Journal made a scientific case for vaccination, there was a great deal of slippage between these arguments and moral judgments on the poor.

London bookie Thomas Gordon Collins told the 1889 Royal Commission on Vaccination that he ‘regarded it as a grievance that clergymen and people of position are not summoned, while working men, like myself, are’ (5). Collins was right. Vaccination officers were appointed to cover working-class areas of London because reformers thought that diseases spread from there to respectable society. Though there were many middle-class opponents of vaccination, they were not sought out or prosecuted.

Persistent vaccination evaders were brought before magistrates, charged and fined. And if they could not pay the fines, their furniture and other goods were auctioned by vaccination officers. In 1888, Charles Hayward, a mechanic from Ashford, was fined repeatedly for refusing to vaccinate his two children, until the sum rose to 53 pounds and 12 shillings (around £3,500 in today’s money). He paid it off with the help of money raised by the London Society for the Abolition of Compulsory Vaccinations. Another persistent offender, Mrs Blanchard, was jailed for seven days. And when she still refused to vaccinate her children, she was jailed for another 14 days (6). That the vaccination officers were mostly appointed from the hated Poor Law administration only compounded the distrust they faced.

Another provocation in the vaccination rules was that parents of newly vaccinated infants were obliged to bring their children back a month later, so that matter from their lesions (called ‘lymph’) could be used to vaccinate others. Many parents thought this was cruel and revolting. In 1891, Lydia Cook, the wife of a railway labourer, was fined and threatened with 14 days in prison for refusing to allow lymph to be taken from her child.

Vaccination programmes were taken up by employers but opposed by employees. The Midland Railway Company demanded its workers be vaccinated but they refused and threatened strike action. During an outbreak in Sheffield in 1887, thousands were vaccinated and re-vaccinated in workshops under the implicit threat of sacking if they did not agree. Ten years later, workers in Gloucester were threatened with the sack if they did not get vaccinated. Working-class districts of London – like Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, Mile End and Southwark – had active anti-vaccination societies and had high levels of non-compliance.

Radical societies in Keighley, Reading and London opposed vaccination, too. The International Herald, journal of the International Working Men’s Association, carried anti-vaccination notices. Socialists were found on both sides of the argument – some seeing vaccination as the greater good, others objecting to the oppressive measures to enforce it. Karl Marx was vaccinated and was sure it had saved Jenny Marx’s life (8). In 1904, the Durham Cokemen’s and Labourers’ Association declared that ‘when vaccination interferes with the employment of labour it is going a step too far’ (9).

With the resurrection of the trade-union movement and the extension of the franchise in the 1880s, some of the loftier pretensions of the liberal reformers were reined in. In 1886, the Contagious Diseases Act was finally repealed after a concerted campaign by women against its oppressive measures. A new Act of 1898, following the Royal Commission’s investigation into the evasion, opposition and administration of vaccination, conceded the voluntary principle that people could opt out of having their children vaccinated, according to their conscience. When magistrates baulked at this measure, unwilling to believe that the commoners before them were actually in possession of a conscience, the law was amended again to make the possibility of opting out more explicit.

To this day, many commentators think that coercion is justified in defence of public health. Arguments over ‘vaccine passports’ and obligations to get vaccinated in contracts of employment are already raging. The voluntary principle, however, is a good one. It is what allowed Britain’s vaccination programme to move beyond the controversies of the 1880s, squaring the circle of vaccination and opposition by letting people opt out. Pointedly, the conscientious objection clause over time killed off Britain’s anti-vaccine campaigns by removing the causes célèbres of vaccine martyrdom.

In response to the horrors of the Nazi regime’s perverse ‘social hygiene’ programmes in the 1930s and 1940s, the European Convention on Human Rights contains a clause saying that nobody should be obliged to have a medical procedure against their will. Today, the NHS’s Covid-19 National Immunisation Vaccination System computer programme will not let vaccinators proceed without checking that the recipient consents.

Voluntarism, in the end, proved to be a tremendous success. In the postwar years, the NHS vaccination campaigns against polio, tuberculosis, diphtheria, mumps and measles worked because they engaged the positive support of the population. Under the terrible challenge of coronavirus, the temptation to use coercion in health provision is strong, but history shows why the voluntary principle is still best.

James Heartfield is a vaccinator with Guy’s and St Thomas’s Hospital.

Picture by: Getty.

(1) Between Hope and Fear: A History of Vaccines and Human Immunity, by Michael Kinch, Simon and Schuster, 2018, p40

(2) Bodily Matters: The Anti-Vaccination Movement in England, 1853-1907, by Nadja Durbach, Duke University Press, 2005, pp50-51

(3) Outcast London: A Study in the Relationship Between Classes in Victorian Society, by Gareth Stedman Jones, Verso, 2013

(4) Dangerous Sexualities: Medico-Moral Politics in England Since 1830, by Frank Mort, Routledge, 2000

(5) Durbach, p99

(6) Durbach, pp101-103

(7) Durbach, p93

(8) Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works: Volume 41, pp220-1

(9) Durbach, p44

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.