We must never return to local lockdowns

Local restrictions are costly and ineffective, so why is the government considering more of them?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

If Churchill was right that those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it, why does Boris Johnson refuse to learn from his hero? As most of the country looks forward to reopening, one of last year’s least successful policies could be revived: local lockdowns.

Less than a year ago, the government imposed the first local lockdown on Leicester. As the rest of England came out of lockdown, Leicester’s pubs, cafés and non-essential shops were not allowed to reopen, schools were shut again, people were forbidden from meeting indoors and only essential travel was allowed in and out of the city.

As it turned out, although there had been a local outbreak, infections in Leicester were falling well before the lockdown was imposed. Furthermore, the local lockdown had no apparent impact on the local trends in infections or deaths. The policy had seemingly zero benefit – but it did impose significant costs to local businesses and people. At the time, I wrote that ‘the right response to local outbreaks and spikes should be testing, information and advice, not the imposition of costly legal restrictions’.

The government, however, was undeterred by the actual data and proceeded with its strategy of imposing more and more local restrictions and lockdowns. Greater Manchester and parts of West Yorkshire were next in line. Eventually, the policy was expanded across the country with the introduction of tiered restrictions in early October.

The impact of the tiered restrictions was roughly the same as the Leicester pilot. Cases rose and fell across the country with little relation to restrictions. Throughout September, Liverpool experienced a big increase in infections and was put under Tier 2 restrictions when the system came in. By mid-October, cases in Liverpool were in decline. Despite this, the government put Liverpool into Tier 3, which made no apparent impact on the already downward trend. Nottingham also endured a big increase in cases that turned around even before it was put into Tier 2. Again, that didn’t stop the government imposing Tier 3 restrictions on the city. Most notably, in Bolton, new restrictions were continuously added from July onwards. These did nothing to stop infections from rising. By the autumn, Bolton had some of the highest infection rates in England.

The aim of local restrictions was to stop local outbreaks spreading and therefore to avoid more widespread regional or national lockdowns. As we now know, two national lockdowns followed the tiered system. In Leicester, it was a criminal offence to invite even one other person into your home from March 2020 until May this year. There is little evidence that the policy of local lockdowns had much benefit, either on the local areas themselves or on the country more broadly. Yet they imposed huge economic and social costs.

At around the same time that local lockdowns arrived in England, governor of Florida Ron DeSantis decided to take a completely different route. He abandoned nearly all state-level restrictions, capacity rules in hospitality and the state mask mandate. Florida did have a big increase in infections and hospitalisations over the winter. But the scale of its winter epidemic was little different to other US states that stuck to the lockdown strategy. After cases and hospitalisations reached their peak in Florida, they decreased around the same time as they did in other states. The lesson from both the UK and the US could not be clearer: local restrictions do not make much difference.

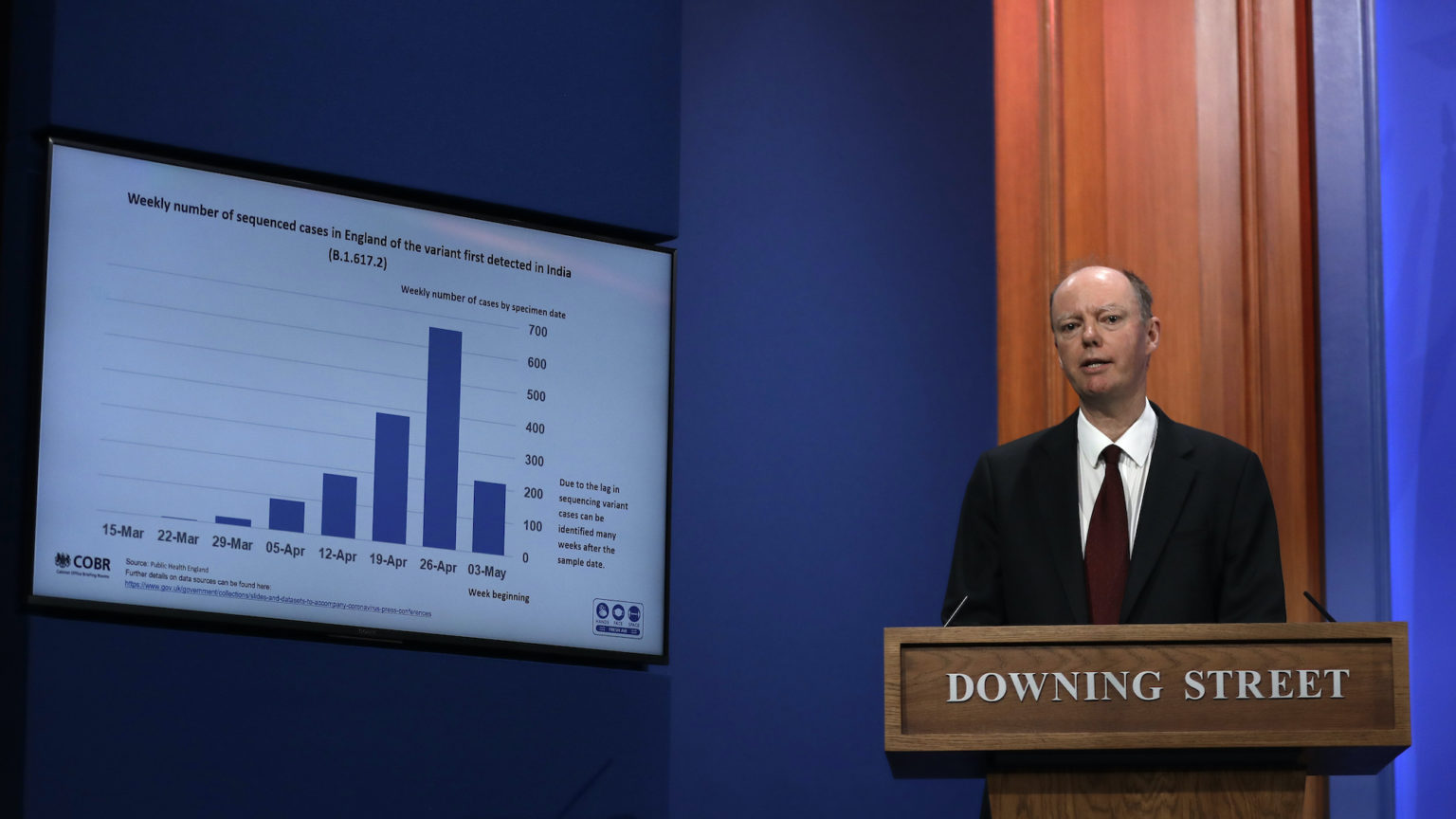

And yet, on Monday last week, a leak revealed that officials were working on plans to reintroduce local lockdowns this summer. Then, on Friday, the government quietly issued guidance against indoor mixing and travel into and out of eight local areas affected by outbreaks linked to the so-called Indian variant. Almost unbelievably, the government did not even bother to inform some of the affected local authorities before changing the guidance. And irony of ironies, two of the eight areas targeted for the stricter guidance – Bolton and Leicester – are exactly where the local-lockdown strategy failed so noticeably last year.

This guidance was issued despite the fact that testing positivity rates – a key indicator of underlying infections – in some of the affected areas, such as Bolton and Hounslow, were already showing signs of decline. Following a backlash from local MPs, the government has toned down the guidance. Nevertheless, the prospect of renewed local lockdowns remains real.

The prime minister has still not ruled out reintroducing local lockdowns, even though all the data and evidence from the very recent past tells us they will not work. If Boris refuses to learn even from recent history, this will be an inexcusable mistake.

David Paton is professor of industrial economics at Nottingham University Business School. He tweets as @CricketWyvern. He is a member of the Health Advisory and Recovery Team (HART).

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.